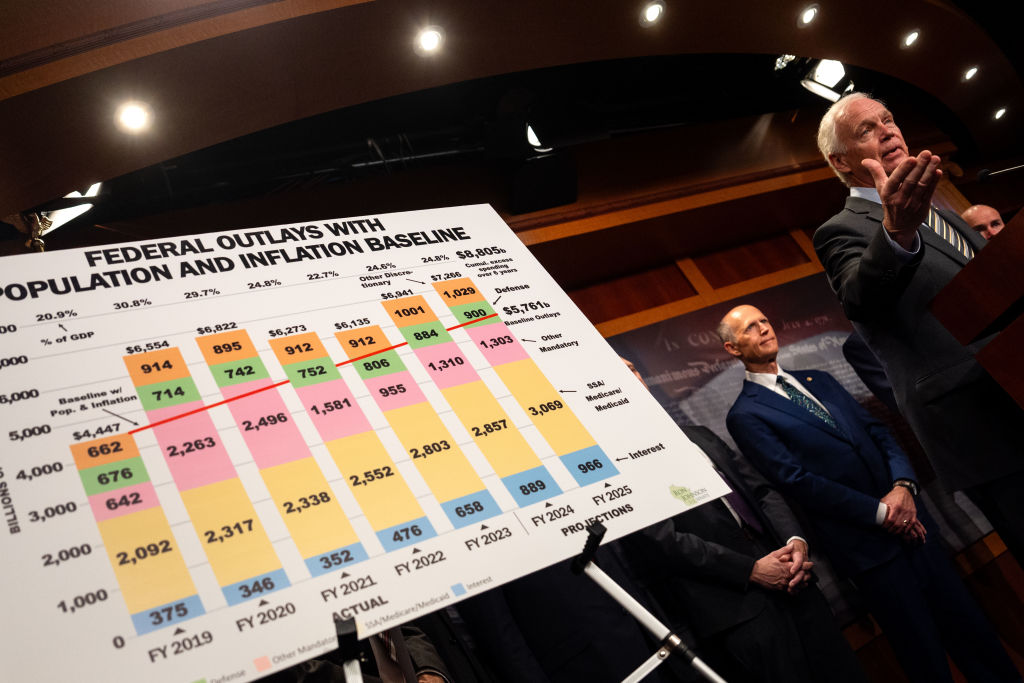

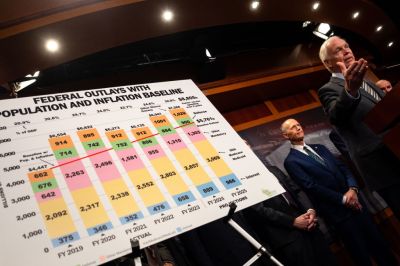

Some political problems are ideological and philosophical: What should be the moral basis of our thinking about abortion? Some of them are matters of priority: How big an economic price are we willing to pay to meet climate goals? Others are mainly—I was tempted to write “simply,” but that isn’t quite right—matters of design, which brings me to the news of the day: spending controls.

Outside of a few cranks and economic illiterates—I mean such figures as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders, who are the economic equivalent of flat-earthers—pretty much everybody agrees that government at all levels requires spending controls and that this is critically true at the federal level, where debt is more of an issue than it is with the states and municipalities. It would be great if we could trust prudent green-eyeshade types to impose fiscal discipline on their own, but that would require having a Congress full of people willing to tell We the People to go stuff it when We the People, in their infallible wisdom, demand big spending and relatively low taxes.

Since that ain’t gonna happen, we need some formal rules and procedures. But it is really, really hard to come up with good ones that are politically durable while also doing anything useful on the debt-and-deficit front.

“Statutory budget controls—Gramm-Rudman, budget sequestration, etc.—have run into political trouble not because they don’t work but because they do, and, when they start working, people complain.”

A looming government shutdown has been avoided for now—in France, which has had four different prime ministers this year and where the senate has just signed off on a stopgap measure that will keep the government operating while the latest PM, the centrist Francois Bayrou, works out a new budget bill, which probably will not happen until early in the new year.

In the United States, things are looking a little different: Unless a deal is worked out and passed, government spending authority will lapse at one minute after midnight this evening. Donald Trump, who before entering politics had been an incompetent businessman who went to bankruptcy court even more often than he has been to divorce court, loves debt and wants Congress to revoke the statutory limit on federal debt as part of a deal to keep the government operating; short of that, he wants the debt ceiling raised before he enters office for purely political reasons as he himself frankly concedes, i.e., so that he can avoid the embarrassment of having to sign a debt-ceiling increase on his own watch. Hence, U.S. public finances are being held hostage to the petty vanity of an economic imbecile. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson—who, for his many mortal sins, absolutely deserves to be leading the Republican caucus—had already negotiated a deal with Democrats, and Democrats are not especially keen on giving up that deal for one that would be, from their point of view, inferior.

Statutory budget controls—Gramm-Rudman, budget sequestration, etc.—have run into political trouble not because they don’t work but because they do, and, when they start working, people complain, and so Congress guts them or sets them aside or waters them down into nothing. Various gimmicks have been proposed, such as suspending congressional salaries if Congress fails to produce a satisfactory budget, but these are likely to come to nothing, because Congress can always vote to relieve itself if the situation becomes too uncomfortable for its members.

It is possible to imagine measures that might improve the situation somewhat, such as painful measures (say, suspending Social Security payments) that would kick in six months before a shutdown crisis if the debt ceiling hadn’t been dealt with or a budget or appropriations bills passed. But those would suffer from the same shortcomings as any other similar measure—Congress could simply suspend it—and would also create some ugly incentives for outgoing members of Congress who might want to create a fiscal and economic mess for the next Congress. Returning to regular order rather than relying on stopgap measures would be preferable to the current ad-hocracy, but regular order isn’t a solution if it is not regular order in the pursuit of sane fiscal policies.

Under a debt-loving Republican president such as Trump and congressional Republicans who are afraid to assert themselves against him in any case and have almost no incentive to do so in the pursuit of unpopular policies (which budget-balancing measures always will be) or under a Democratic trifecta (in which no one would have any particular incentive to cut anything, though they might raise some taxes very modestly), the political pressure to impose fiscal discipline will never be half as strong as the pressure to keep borrowing and spending and keeping the gravy-train rolling down the tracks until it derails, which might not be for a very long time—or at least not until after the next election.

So what we most need is a way to manage our fiscal affairs without lurching from crisis to crisis—and what we do not have is a powerful political incentive to manage our fiscal affairs without lurching from crisis to crisis.

So far, the crises mostly haven’t been that bad. The occasional shutdown reminds the world that the United States is a country that is powerful not because it is governed well but because it is rich, and that the United States is rich in spite of its not being governed very well at all since around the time of the Eisenhower administration. In response, the world shrugs and sniffs and makes rueful little noises and wishes that its GDP/capita were more like ours and then goes on stockpiling dollars and investing in U.S.-based assets.

But that won’t be true forever.

Everybody knows what needs to be done. Nobody will do it. Anybody who tried to do it probably would suffer political annihilation at the next election. After the trainwreck, Americans will be looking around for someone to blame. They won’t need to look far.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.