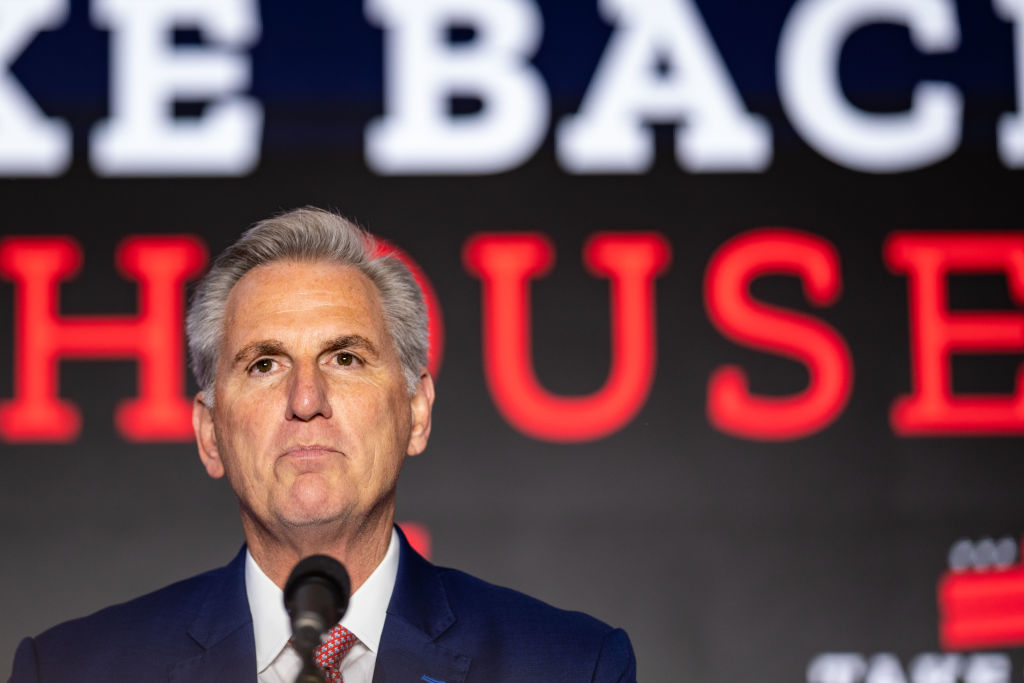

By early Wednesday morning, it remained unclear whether Republicans would retake the House. Yet one thing quickly became clear on Election Night: GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy’s path to becoming speaker will be a lot rockier than expected.

It could be days, or even weeks, before we’ll know the exact breakdown of seats. Yet the results on Election Night were undoubtedly disappointing for Republicans. Vulnerable Democrats like Rep. Abigail Spanberger won reelection as other expected GOP wins failed to materialize across the country.

McCarthy’s first challenge will be marshaling enough votes to get the speaker’s gavel. He needs buy-in from a House majority of 218 members, unless some lawmakers who would otherwise vote for someone else throw him a lifeline by choosing to vote “present,” a procedural work-around.

“A GOP House with only 228 or so seats seems like a nightmare for McCarthy, somewhere between unmanageable and ungovernable,” wrote Matt Glassman, a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Government Affairs Institute. “Even the Speakership vote sounds like a headache.”

McCarthy will face backlash from members who had expected far stronger results—he once suggested the party could flip more than 60 seats in these midterms—and his caucus could look elsewhere for fresh leadership. And if the California Republican manages to get the job, pulling together votes for legislation will be a pain as well.

A smaller margin for the House majority will make rank-and-file Republicans—particularly radical members who have power with the party’s base—even more potent. It’s a question of simple math: A smaller majority means fewer members need to band together to affect vote outcomes and call leadership positions into question.

House Republicans have had a fractious coalition for years, but their current divides in the Trump era threaten to grow out of control: A vocal contingent of far-right, Trump-aligned members oppose new military aid to Ukraine, for example. Senior policymakers in the party generally disagree, but it’s unclear who will win that fight.

Some members of the House Freedom Caucus also believe President Joe Biden and some of his Cabinet secretaries should be impeached—something McCarthy has pushed back on in recent interviews. Those clashes, and others surrounding government spending, could escalate and make it difficult for Republican leaders to hold onto power in a majority with very little margin for disagreement.

Democrats faced the dilemma of a small majority after the 2020 election, and it required deft navigation by the party’s leaders. But it is a far more perilous dynamic for leaders dealing with a divided government: McCarthy, if he does become speaker, will have to handle high-stakes negotiations with the White House to fund the government, approve must-pass defense authorization bills, and avert a debt ceiling disaster next year. Those negotiations—representing some of the only opportunities for House Republicans to craft law under a Democratic president—could become major showdowns and quickly turn an already fractious conference into utter chaos.

That’s why Josh Huder, another senior fellow at Georgetown’s Government Affairs Institute, toldThe Dispatch last week that McCarthy, if Republicans win the House, “is essentially entering an early retirement plan from politics.” That is, if he manages to win the speakership at all.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.