GREENEVILLE, Tennessee—Friday was turning to Saturday when the Tennessee Valley Authority did something it had never done in its 91-year history: It sent residents a “condition red” warning that one of its 49 dams was in danger of an “imminent breach.” Everyone near the Nolichucky Dam, seven miles south of the eastern Tennessee town of Greeneville, needed to evacuate.

After nearly three days of nonstop rainfall on September 25, 26, and 27, and as the outer bands of Hurricane Helene pulled the storm’s center from the Gulf of Mexico up into southern Appalachia, the little dam that for 111 years had slowed down the waters of the Nolichucky River was withstanding a flow rate of nearly double that of Niagara Falls.

The men who anchored the concrete structure through 2 feet of sand and into the river’s dolomite bed in 1912 and 1913 could scarcely have imagined the force it would stand against more than a century later. Their main objective in building the dam wasn’t to hold back the Nolichucky so much as it was to harness its waters to bring the wonders of electricity to the region.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)—the federal New Deal-era energy utility—manages 49 dams stretching from northern Alabama to southwestern Virginia, and as far east as North Carolina. In its entire existence, it had never experienced this kind of massive deluge in the tributaries feeding into the Tennessee River. But then, the flooding that submerged much of southern Appalachia was no 100-year flood. TVA’s data revealed that the rain that fell over the Nolichucky River watershed was equal to about a once-in-5,000-years rain event. Put simply: The Nolichucky Dam had never withstood anything like that before.

Nothing in the region since the advent of historical records had.

By the time the center of the storm had made it to the southern Appalachians, 10 inches of rain had already fallen in the previous two days in some places. When the rain stopped on September 28, the National Weather Service had recorded more than 30 inches of rainfall in one North Carolina county. Places like Spruce Pine and Hendersonville in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains saw upward of 20 inches. Much news coverage has focused on the devastation to property and life in Asheville in Buncombe County, which received more than 17 inches of rainfall: At least 42 people there are confirmed dead, some residents are still without running water, and some businesses and schools remain closed.

Across the region, trillions of gallons of water rushed down from the mountains, into creeks and rivers like the Nolichucky and Pigeon rivers in Tennessee, and the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers in North Carolina, which in places erupted from their channels and destroyed anything in their paths. The U.S. Geological Survey recorded more than 400 landslides in the region.

The National Weather Service’s summation of the damage in Yancey County in western North Carolina reads like the summaries of several other mountain counties:

Major to catastrophic flooding of streams, creeks, and mainstream rivers. Widespread wind damage occurred on top of devastating floods. Widespread trees and powerlines were downed. At least hundreds of homes and businesses were flooded, with many likely destroyed. Widespread road closures, bridges completely wiped out, and roads completely washed away. The extent of landslides are unknown, but pictures and videos would indicate that landslides were very common, especially along steeper slopes.

The latest death toll for the Carolinas, Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia stands at 224, with at least 26 people in North Carolina still unaccounted for.

Recovering from a disaster that not only erased homes and livelihoods but plowed river channels into new paths will take lots of grit. In the National Weather Service’s post-Helene impact reports, each affected county’s summation ends with the same basic prognosis: “Communities were essentially cut off from society due to roads being washed away. Several small communities will likely have to be completely rebuilt. Recovery will take months, if not several years in the hardest hit locations.”

After Helene, the question for the region is the same question the Nolichucky Dam faced the night of September 27: Can it hold and, if so, how?

“There are a lot of communities that are just totally cut off,” Amanda Held Opelt, a writer and musician who lives north of Boone, North Carolina, said a few days after the storm passed. “They’re like islands.”

Life in Appalachia has always been shaped by the land itself. Appalachian communities and thoroughfares aren’t laid out in grids and right angles. Instead they sprung up along the creeks, rivers, and ridges that form the region’s spine. Small coves and valleys—often known as “hollers”—tucked into the folds of mountains and waterways have become their own communities as the region’s population has grown over the last two centuries. “In each of those hollers, it’s kind of like your neighborhood or your subdivision in a way,” Michael Moore, a physical therapist in Boone, said. “Each holler is named after a guy who settled it or built everything back there.”

The physical isolation the land itself imposed has resulted in a sort of cultural isolation for some Appalachians: A more hardscrabble way of life, cut into the mountains’ clefts and in foothills and that requires independence and resourcefulness for getting the most out of the land, can look very different from life in other parts of the U.S. (and give rise to stereotypes such as the idea of the dumb hillbilly). No doubt some are attracted to it because they seek isolation and simplicity. Some are here because their familial roots run deep. Some are here because this may be the only place they know. “There’s kind of this judgment that if you live in such isolation, you deserve it,” Opelt said of some sentiment toward Appalachians and natural disasters.

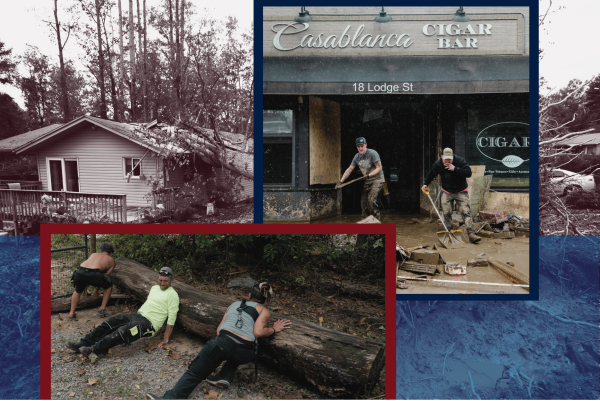

That pockets of Appalachia are sparsely populated, geographically isolated, sometimes materially impoverished, and susceptible to health and substance abuse problems is not news. The destruction created by Hurricane Helene, however, is illuminating a resourcefulness that has always been there but hasn’t been needed to this degree for generations.

That recovery has had to begin with regaining access to places and people still mucking themselves out of the mud and debris. The September 27 flooding severed the two main arteries connecting Tennessee to North Carolina. Interstate 40, which curls through the mountains between Knoxville and Asheville, closed that day when parts of it crumbled away. Farther north, the same thing happened to I-26, which runs from the highlands in northeast Tennessee to Asheville. Hundreds of smaller thoroughfares remain closed. After Helene’s historic floods destroyed interstate and country road alike, individual cities and communities were cut off from each other. Asheville, a city of nearly 100,000 people, was completely isolated for several days because of roads and bridges being gone or underwater.

The hollers and coves in the mountains were even more isolated—and some still are. What became most important in those situations were neighbors helping neighbors.

Opelt went with teams from her church to Spruce Pine and Bakersfield, some of the hardest hit spots in rural North Carolina, to help hike in supplies where roads were impassable and check in on folks who couldn’t get out. She was surprised to find even those who needed help were so upbeat—“Everyone I’ve met has been positive … smiling and laughing when we visited them”—and making use of the resources at hand. Some without power used cold creeks to preserve food that had been in their refrigerators, others used creekwater for washing clothes and even themselves. Neighbors shared produce from their vegetable gardens and fished with each other. “What I hope people have the opportunity to see is Appalachian resourcefulness—it’s a different kind of intelligence,” she said. “I see it as vitality and deep communal ties. You do not leave your neighbor behind.”

Moore spent several days of the first week after the floods volunteering on a chainsaw gang with other members of his church. Many of the communities he worked in—Valle Crucis, Banner Elk, Newland, Minneapolis, Cove Creek—have only one way in or out, and those arteries were destroyed by flood waters or the massive amounts of debris that swept through the mountains’ crooks and crannies.

Michael Moore“We don’t know how much of the road is there structurally. You’re driving around trying to stay away from the shoulder on either side because you don’t know how hollow it is underneath.”

Moore said in places like these, getting through the “marriage of trees and powerlines” represented one of the biggest challenges for volunteers looking to reach people cut off by the storm, as did the roads themselves. “We don’t know how much of the road is there structurally,” he told The Dispatch. “You’re driving around trying to stay away from the shoulder on either side because you don’t know how hollow it is underneath.”

All over the region, volunteer fire departments and small country churches became the nerve centers for recovery: temporary landing zones for helicopters bringing in supplies; a staging area for bottled water, medications, food, and other basics; and the hub for volunteers like Moore fanning out into the nooks of the Blue Ridge. Volunteer firefighters become de facto emergency response coordinators, and pastors and churchgoers become civilian quartermasters.

Four days after the worst of the flooding hit, Moore and his chainsaw crew stopped in at the Frank Volunteer Fire Department in Newland one day for lunch. Outside, a convoy of cars lined up with volunteers waiting to pick up bottled water, jars of peanut butter, and MREs. A small, two-seat helicopter landed to grab a batch of supplies to take to its next stop. “They were there for maybe two minutes and they were up in the air again,” Moore said.

Inside, he estimated somewhere between 100 and 200 people picking up supplies, dropping off supplies, and building meals to take out to those who needed them. “There’s dirt and mud everywhere,” he remembered. Inside, three or four women in T-shirts, jeans, and boots fixed plates for any volunteers who looked hungry. They piled brisket tacos, cheese, beans, rice, salsa, and chips on a plate for Moore—and like a doting grandmother kept piling it on, even when he said he had plenty. “They don’t know my name, but to them I’m darlin’,” Moore said.

He saw the same generosity at churches his team members stopped at to coordinate where they were needed for clearing roadways. Pastors directed them to where the needs were and helped people in the community connect with supplies coming in.

“Churches have done a great job of trying to gather resources,” Moore said. “Everybody knows everybody—nobody goes unaccounted for. It’s like they’re family.”

Back across the mountains in Tennessee, what lies immediately downstream of the Nolichucky Dam near Greeneville is much like what lies upstream of it: homesteads, farms, bridges, schools, and people. As September 27 turned into September 28, Helene’s flooding had already killed 14 people upstream of the dam and three people downstream. It had destroyed six bridges spanning the river. A break in the dam would further imperil the small communities immediately downstream and their residents.

TVA’s river management specialists were watching from their headquarters in Knoxville throughout the night. The Nolichucky River flows into the French Broad River, which eventually flows west into what’s called the Douglas Reservoir, before forming part of the headwaters of the Tennessee River. One of TVA’s main objectives with its tributaries such as the Nolichucky is to manage—for both power generation and flood control—what flows into the Tennessee River near Knoxville and mitigate disastrous flooding that plagued its watershed prior to TVA’s creation by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But there was nothing TVA could do to ease pressure on the Nolichucky Dam. It’s a passover dam, meaning TVA cannot open spillways to regulate how much water passes over it and downstream. What the river does, the river does.

Darrell Guinn leads the river management team in Knoxville. From its monitoring center on September 27, his analysts were crunching numbers on flow rates and water volumes, while also using forecasting models for rainfall amounts to try to predict how much higher the water in rivers like the Nolichucky would get. But so much rain had fallen in North Carolina and was shooting down into the Nolichucky so fast, existing forecast modeling wasn’t accurate with actual water levels.

“It was outpacing anything we had ever seen before,” Guinn said. “There was no calculation for them.”

In such events, Guinn’s team is in constant contact with dam technicians and safety teams on the ground, along with local emergency management officials who decide if and when to evacuate residents. But that night, with power transmission lines and cell phone towers down across the region, those teams faced many of the same communication problems that plagued everyone else. “We were working to send folks to the nearest place that had cell service, them taking that phone call … and from there going back up to the dam, relaying that information,” he said.

The problem for TVA personnel monitoring the Nolichucky Dam was that between unprecedented water levels, upstream water-level gauges having been destroyed by flooding, and the fact that it was after dark, it was impossible to gauge whether the dam was holding.

In Greeneville, which sits on the northern side of the mountains from North Carolina, John Kitsteiner had a unique perspective on the disaster. An Air Force veteran, Kitsteiner runs the emergency department at Greeneville Community Hospital and also oversees Greene County’s EMS personnel. The physician spent most of the time immediately after the Nolichucky River crested in the ER. The initial flood divided Greene County—five of the eight bridges spanning the Nolichucky were either destroyed or deemed too unstable to use—and kept many of his staff members stranded at home.

One of Kitsteiner’s nurses, 32-year-old Boone McCrary, didn’t wait around to get stranded. After the Nolichucky began to rise on September 27, McCrary, his girlfriend, and his dog got in his small fishing boat and set out searching for people he had heard needed to be rescued. At one point, the river pushed him toward a bridge and eventually swept him under. His girlfriend was able to escape, but emergency workers found McCrary’s body 21 miles downstream four days later (his dog’s body was found later too).

McCrary was the only flood-related fatality in Greene County.

Five days after the worst of the flooding, it became clear to Kitsteiner that the bigger needs in his community would be the longer-term recovery and restoration. He and a physician’s assistant at the hospital knew how dire Asheville’s situation was, so they drove through the mountains to see how they could help. “I can go shovel mud. It is not beneath me to do that,” Kitsteiner said. “But I want to offer my services at the peak of what they’re able to do, at the greatest extent that they can give.”

As they got into the outskirts of Asheville, Kitsteiner said the damage didn’t initially look that bad. But they encountered more and more debris and eventually arrived at a wall of vehicles strewn over the road and buildings moved off their foundations. Down a side street they spotted a rescue team among the mess and stopped to offer help. “They were waiting for cadaver dogs and excavators,” he said. “They knew there were bodies there, but it was going to take a while to get them.”

Kitsteiner and his colleague moved on, and eventually found their way to a local school serving as a disaster response center. When Kitsteiner asked how he could help, organizers asked if he could set up a walk-in clinic to serve a part of town that had no other clinics operating. Kitsteiner said he was in. “The people we spoke to were on fumes,” he said.

He and the PA returned to Greeneville and began making phone calls and posting messages on social media asking for medically trained volunteers. Soon he had a team coordinating volunteers, building a website for the clinic, and organizing donations, including some from the company that runs his hospital, Ballad Health. Within days he had more than 200 physicians, nurses, and other volunteers asking to help—more than he could accept.

The state of North Carolina granted Kitsteiner an emergency provisional medical license, and a week after his initial trip to Asheville, the clinic opened, providing free care for any medical ailment it can—the first such clinic to open in West Asheville after the floods.

Yet Kitsteiner and his team weren’t content to let patients come to them. Three days after the walk-in clinic opened, it began sending medical teams to isolated hollers in the mountains to help people who still couldn’t make it out. Each team consisted of a physician who could write prescriptions, one or two nurses, a medic, and a non-medical volunteer to help with logistics and paperwork. The teams treated any acute medical conditions they could, wrote prescriptions for those who needed them, had the scripts filled at a pharmacy near the walk-in clinic, then delivered them to the patients.

John Kitsteiner“There are a lot of people in our community that were out doing as much as they could, literally digging their neighbors out of the storm damage and the flood damage.”

The clinic has since ended its operations as other medical facilities came back online, but its existence was a function of Kitsteiner and his colleague seeing neighbors—albeit across-the-mountains neighbors instead of across-the-fence neighbors—in need and rallying others to help. Most of his volunteers were from his eastern Tennessee community, though many from western North Carolina joined too—along with some from other parts of the country who saw Kitsteiner’s pleas on social media. “There are a lot of people in our community that were out doing as much as they could, literally digging their neighbors out of the storm damage and the flood damage,” Kitsteiner said. “And as Greene County started to get their heads literally above water, they started looking for other ways they could help the community.”

Barry Bales, who has won more than 15 Grammy Awards and been the bass player for Allison Krauss & Union Station for more than 30 years, has seen that same Appalachian neighborliness. Instead of living in the country music capital of the world, he lives in southern Greene County on a farm that has been in his family since 1882. His home was spared from the flooding, but it became a nerve center of its own in which he helped coordinate resources in the area, including with Kitsteiner and the Asheville clinic. Two days after the floods hit, Bales was, like most of Greene County, without water to his home. When he heard about a bottled water distribution effort at a nearby volunteer fire department, he and his family went to help. The fire chief put Bales’ wife and son on a firetruck that set off in a caravan to deliver water to people who couldn’t get to the distribution site.

He credits volunteer firefighters for taking it upon themselves to care for their people. “That’s what is special about this part of the world,” he said. “And I think this kind of spirit is ingrained.”

And especially in a situation when creeks swelled to rivers, isolating entire neighborhoods or hollers, it became incumbent on local people to mobilize since help from outside would be long in coming.

“Hillbillies can get things done,” Bales said. “And they are.”

The historical hillbilly caricature of shoeless mountain men toting their jugs of moonshine—and the more contemporary stereotype of overall-clad, gun-toting farmers trekking into town for a trip to the Dollar General—by definition exaggerate the reality of the region. But confronting isolation played at least a part in inspiring a bunch of hillbillies to build the Nolichucky Dam in the first place. It exists because leaders in Greeneville and neighboring cities of Jonesborough and Johnson City saw the promise of hydroelectricity and took it upon themselves to bring it to more of the area. In 1912 those municipalities formed the Tennessee Eastern Electric Company and the same year broke ground on the dam. In October 1913, its electricity lit up homes here, many for the first time, before ceasing those operations in 1972.

Helene’s destructive force exacerbated the already-present isolation in Appalachia. And overcoming that isolation was so much of what Appalachians have done in the recovery since. It’s a familiar story to those who live here.

“It has been topographically and geographically isolated,” Kitsteiner, the Greeneville physician, said. “As we’ve had roads and railways built up around the mountains, a lot of areas got bypassed and felt isolated for generations. Not completely, but just always lagging a little bit behind. And there was always a sense that you really had to rely on your neighbors more than being able to jump on a road or get out if things got tough.”

That—and the region’s innate independent spirit—are obvious in the roving doctors looking for people to treat, legions of chainsaw gangs clearing a path through downed trees, and resourceful neighbors using the land itself to preserve what they had until help arrived. “This area has a higher percentage of people who have those traits,” Kitsteiner said. “And I think we really capitalized on them during this disaster.”

Opelt put it a bit more simply: “I’m just seeing Appalachians do what Appalachians do.”

When TVA issued its condition red for the Nolichucky Dam late in the night on September 27, no one—not dam safety professionals, not volunteer firefighters evacuating residents, not engineers and analysts in a Knoxville high-rise, and not the people whose homes stood downstream—knew whether that 111-year-old concrete structure would be there in the morning.

But the dam held.

Now in Appalachia, as deaths are counted and damage is assessed, the focus turns to recovering, reopening, and, when it comes to things like basic utilities, restoring. “The danger to life and limb has passed for the most part, and it’s mostly about debris removal and cleanup and rebuilding,” Bales told The Dispatch. “For somebody that might have been displaced, or if their home’s not intact and they don’t have the ability to heat with wood, up there in the mountains winter’s coming sooner than later. …”

“There will be lots of long-term needs. But there are so many good people.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.