Editor’s Note: This is the first of five installments in a story documenting the creation and passage of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The second installment is available here, the third installment is available here, the fourth is here, and the fifth is here. The story is based on more than 21 hours of interviews with more than two dozen people involved, including lawmakers, staff, and human rights advocates. An audio version of the story is available here. Dispatch members can download a PDF of the full report here.

Introduction

Gulzira Auelkhan sat in a room in Midland, Texas, with the people who helped her escape a genocide.

Across from her were American federal law enforcement agents. They had traveled to her new Texas hometown to ask about the roughly 15 months she spent in 2017 and 2018 in concentration camps in Xinjiang, a northwest region of China. They also wanted to know more about her experience being forced to work in a textile factory by Chinese authorities.

With Kazakh activist Serikzhan Bilash translating, Auelkhan, an ethnic Kazakh, told the Americans about the horrors she faced in the camps. She told them about the gloves she and hundreds of other women had to sew for long hours each day, under harsh working conditions. She told them about being driven to the factory early each morning, when it was still dark outside. They were expected to sew 20 pairs of gloves each day, she told them, with the threat of punishment looming if they could not meet quotas.

She spoke about how the women at the factory had only 40 minutes in the day to eat meals and were otherwise under close scrutiny, without the freedom to get water or leave their work. She told the Americans about how she wasn’t paid what she was promised for her labor. She recognized the name of the textile factory—a short bus ride from the camp—and gave other details to the agents from the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security.

“They were very deliberate, very intentional,” says Bob Fu, the Chinese American founder of China Aid who contributed to the rescue effort that culminated in Auelkhan and her family coming to the United States in early 2021.

Just a couple months after arriving in America, she was assisting investigators who wanted to eradicate forced-labor products flooding U.S. markets. Fu was present for the interview, which he says happened at China Aid’s office in April 2021. It lasted hours.

Auelkhan is far from alone in her experience of forced labor in Xinjiang. Her testimony, research from experts around the globe, and reporting from news outlets in recent years have laid bare the facts. China’s genocide in Xinjiang has another purpose, beyond cultural extermination: profit.

Since 2014, the Chinese government has forcibly detained more than 1 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other Turkic Muslim minorities in concentration camps in Xinjiang. These camps—and the larger region, which is now a suffocating police state built around advanced surveillance technology—are home to unspeakable horrors, according to survivors. The Chinese government has subjected Uyghurs to forced abortions and mass forced sterilizations, slashing birth rates. Chinese officials methodically stamp out religion and tradition, aiming to instill reverence for President Xi Jinping in their stead.

Prisoners face inhumane conditions, crowded together without adequate food or medical care. Men and women who escaped from the genocide have testified before Congress and in news interviews about being tortured and raped by guards in the camps. Chinese officials cut detainees off from family members without the means to communicate and with no idea of when or if they might be granted freedom. Many of those who are released aren’t able to go back to their homes: Instead, the Chinese government forces them to work in other parts of China.

The camp survivors who do go home return to families and neighborhoods completely changed. Day and night, police continue to watch them.

The threat of being thrown into the camps hangs over every action. Innocuous behavior like installing a messaging app on a phone, abstaining from alcohol, growing a beard, buying more groceries than usual, briefly studying abroad, or having a family member who lives in another country all raise suspicion.

Chinese agents live in Uyghur homes, forcing families to speak in Mandarin rather than Uyghur. Some women say they have been sexually assaulted by these agents, with no possibility of recourse. Authorities expect neighbors to report on each others’ activities. They make children inform on their parents’ religious observances and reading habits.

Amid all this, the Chinese government has bulldozed thousands of religious sites, mosques, and cemeteries, aiming to wipe out a culture’s historic connection to the land.

It’s a humanitarian nightmare, inconceivable in cruelty and scale. And it is being perpetrated by a country with tremendous economic power.

You probably own something made with Uyghur forced labor.

Xinjiang has a massive role in the global economy, particularly in textiles. Xinjiang produces 85 percent of Chinese cotton and one fifth of the world’s cotton supply. The region’s energy industry is also large. Estimates indicate nearly half of the globe’s polysilicon, a material required for manufacturing solar cells, came from Xinjiang in 2020.

Given the complexity of global supply chains, products with components sourced from the region are difficult to avoid, even when consumers are being careful about their purchases. A mass-produced electronic device might have one small component from Xinjiang, or a company might buy cotton from the region before workers sew articles of clothing in a different country.

In 2018 and 2019, reporting from journalists and researchers began to reveal the sprawling scope of the Chinese government’s use of forced labor in Xinjiang, touching some of the largest brands in the world. Not only is the Chinese government forcing masses of unjustly detained people to work in factories connected to its concentration camps, it is also sending Uyghurs to work in agricultural fields and factories in other parts of China. Research and news reporting have implicated companies such as Nike, Kraft Heinz, Adidas, Calvin Klein, Coca-Cola, Costco, Patagonia, and Tommy Hilfiger. Recent reporting indicates these transfers are only ramping up, even as Chinese authorities are trying to keep the scope of the programs more secret.

As the evidence mounted, American lawmakers itched to respond. By late 2019, members of Congress felt it was time to shore up the United States’ longtime ban on importing products made with forced labor and prevent American dollars from contributing to the Chinese government’s genocide. But it would be an uphill battle. Congress would have to overcome a persistent lobbying campaign by large corporations and resistance from factions in the White House. Lawmakers would also have to make sure such a bill was powerful, so businesses could not easily evade it. And they would need to make difficult concessions to reach a version that could ultimately pass both chambers.

After nearly two years of work, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act passed in December 2021. Its most important provision—a ban on imports touched by Xinjiang, with the potential for exemptions if companies can clearly prove their products are free of forced labor—goes into effect this week.

The law won’t solve the problem of forced labor in China, and it hasn’t ended the genocide. But it presents a meaningful tool for the United States to respond and to pressure the Chinese government to end its brutal human rights abuses. It also means companies will have to more closely examine their supply chains. American consumers may soon have more peace of mind that they aren’t buying items made by people like Auelkhan, in circumstances of extreme suffering and oppression.

Advocates hope the rest of the world will learn from the process of passing the American law and quickly follow suit.

1. Beginnings

It was years in the making, but it started in earnest with a question.

“Do you believe that the U.S. should ban all imports from Xinjiang?” Rep. Jim McGovern asked. It was October 2019, and McGovern was chair of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC). The panel had convened for a hearing on forced labor in the region, home to Turkic ethnic minorities. In asking that question, McGovern offered the first public glimpse of what would become the most significant China legislation in more than two decades.

McGovern was frustrated with the business community’s inability—and, all too often, unwillingness—to rid their supply chains of forced labor. He and the other lawmakers on the commission were looking for how Congress could make a tangible difference.

“That’s a hard question,” said Amy Lehr, an expert in human rights at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. She had co-authored a report on forced labor in Xinjiang published the day before the hearing, and she was well aware of how deeply it permeated global supply chains.

“It will obviously have significant immediate economic repercussions,” she told the panel.

McGovern said he’d had conversations with American companies, and they weren’t trying hard enough to determine if forced labor contributed to their products.

The normal methods businesses use to identify and rid supply chains of forced labor had long been difficult and unreliable in China, but Xinjiang is its own beast. It is impossible for companies to do due diligence in the region. Third-party auditors have no guarantee of access to worksites, nor can they be certain that workers aren’t being intimidated to discourage them from raising alarms about labor conditions. The situation only grew more dire as China expanded its network of concentration camps and factories in Xinjiang.

By the time the lawmakers on the CECC met for the hearing in 2019, it was clear that all goods touched by the region were suspect.

Testifying before the commission, Nury Turkel, current vice-chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom and a high-profile Uyghur advocate, answered McGovern’s question about banning all imports from Xinjiang unequivocally.

“Yes. In one word, yes. That’s necessary.”

He added that the United States should encourage its trade partners to likewise ban Xinjiang imports to place coordinated pressure on China.

“This has to be a global effort,” Turkel said.

Adrian Zenz, a German researcher who has played a critical role in uncovering the scope of China’s atrocities in Xinjiang, also threw his support behind new restrictions.

“At a minimum, the burden of proof should be shifted to the companies,” he told the lawmakers on the panel. Zenz added that a ban on low-skilled, labor-intensive manufacturing items from Xinjiang was also feasible.

“This would send a much stronger message to Beijing than anything else,” he said.

The Chinese government is systematically and brutally trying to erase a people group. But what happens when a genocide is carried out by a country with colossal might on the global stage? We’ve witnessed the answer: Apathy from the business community and lethargy from policy makers. Despite designating the atrocities in Xinjiang a genocide in early 2021, the United States has not done enough to respond. And where America has taken significant action, it has come only after years of pitched lobbying between major corporations and human rights advocates.

This is the story of how the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act became law, marking the United States’ most consequential response to the genocide in Xinjiang to date. To see it advance, the bill’s sponsors had to battle business interests, overcome partisan tensions, grapple with the Biden administration’s climate priorities, and maintain public pressure on officials who were reluctant to get it done.

This account follows the 21 months from the forced labor bill’s introduction in March 2020 to final passage in December 2021. It is based on more than 21 hours of interviews with over two dozen people involved, including staff who shaped the legislation, lawmakers who sponsored it, and outside advocates who helped get it over the finish line.

The path to passing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act was an arduous one, even as the legislation ultimately won broad support across the political spectrum. It wasn’t clear at the beginning, or even close to the end, that it would actually become law.

Jonathan Stivers, who served as CECC staff director when the bill was introduced, was skeptical of its chances to begin with.

“I had no idea how far it was going to go,” he says. “I thought there was no way Congress was going to pass this. All the entrenched interests are going to come out in opposition to this.”

Stivers would know. He has spent decades working in Congress and on China policy issues. He remembers the October 2019 hearing vividly, having sat behind McGovern throughout. When McGovern asked the witnesses about barring imports from Xinjiang, Stivers listened carefully to see if any of the witnesses would give a credible reason not to go ahead with the bill the commission staff had been quietly contemplating. They didn’t.

Turkel, who testified at the hearing, says he wasn’t exactly surprised by McGovern’s question. In the months leading up to that exchange, Turkel had been on the other end of brainstorming conversations with the man who came up with the idea of a region-wide import ban in the first place: Scott Flipse, a longtime human rights policy hand who works on the CECC. Flipse has played a leading role in crafting America’s legislative response to China’s genocide in Xinjiang, so much so that Turkel has given him a nickname—“Thomas Jefferson of the Uyghurs.” Flipse’s idea for an import ban was a departure from the approach human rights bills often take—commissioning reports, statements of policy, and sanctioning officials responsible for abuses, for example. Instead, it leaned more into the uncomfortable world of trade policy.

“This bill may be the most significant legislative mandate, arguably, put in place by Congress to address some of the lingering issues in U.S.-China trade,” Turkel says.

After the 2019 hearing, the top lawmakers on the CECC were ready to take the idea to the next level. McGovern soon gave approval for the CECC team to finalize legislation he could introduce. Over the next five months, staff on the commission compiled a comprehensive report on forced labor in Xinjiang, including links to large companies. And they hammered out a bill to block items made with forced labor in Xinjiang from entering the United States.

“We were brainstorming a lot about this,” Stivers says. The CECC staff were concerned about how broad the implications might be.

“Whole supply chains will be totally changed. It’s like, oh my gosh. That’s a big thing. But the arguments are so clear. It’s so compelling and so clear that you have to do it. And then the question is: Could you do it? I mean, we’re not going to ban all trade from China.”

The centerpiece of the bill was a presumption that all products from the region are tainted by forced labor. Under the measure, all items made in part or in whole in Xinjiang would be blocked from coming into the United States. To obtain an exemption from the ban from Customs and Border Protection, companies with implicated supply chains would have to prove with “clear and convincing” evidence that their products are free of forced labor. Those exemptions were expected to be few and far between, given the realities of the situation, and the government would have to make any such decisions public.

Another key component of the proposal: language aimed at protecting American investors from unwittingly contributing to the atrocities in Xinjiang. Under new reporting rules, businesses would have to regularly disclose known connections with specific bad actors—producers of surveillance technology used in Xinjiang, those involved in constructing detention or manufacturing facilities, and other actors tied to human rights abuses in the region—to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

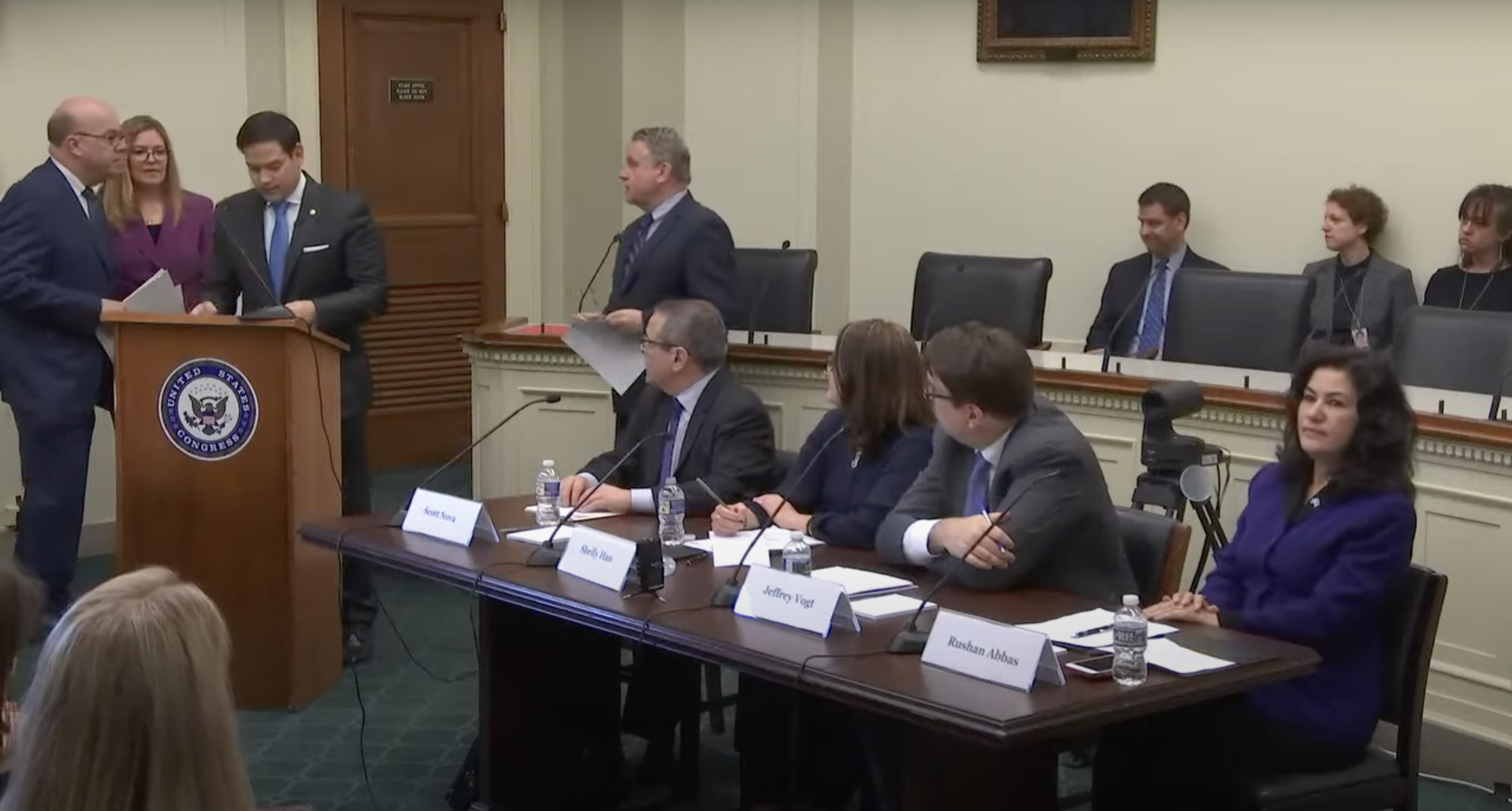

Stivers recalls some anxiety when McGovern, alongside then-CECC Co-Chair Sen. Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican, introduced the plan in early March 2020.

“Here's something, and something significant,” Stivers says. “This isn’t just a new office in the State Department or a report. This is an import ban, more or less. This is a big deal.”

“We were nervous because we didn’t know what the response would be.”

On March 11, 2020, leading lawmakers on the CECC, congressional staff, and human rights advocates crammed together in a room in the labyrinthine Rayburn House Office Building. They had gathered to announce the introduction of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, but the mood was surreal. That week, Americans were starting to see how the coronavirus pandemic—which had already upended much of the world—would do the same in America. It was enough to inspire some angst among attendees, but the situation hadn’t yet escalated enough in the nation’s capital for staff to cancel the event.

“We’re all just learning how to do the fistbump, elbow-bump greeting,” Rubio quipped during his opening remarks.

One senior Senate Democratic aide remembers the number of attendees as absurd in hindsight; it was one of the most packed rooms he’d been in on Capitol Hill in years.

“The fact that it was as COVID was spreading was crazy,” he says. “But, we didn’t know. We didn’t know.”

The pandemic would make this unlike prior legislative pushes, but it only amplified a technology-fueled shift in legislating and lobbying that had already been apparent in recent years. Gone were the days of hearing room hallways packed with Gucci-clad lobbyists vying for their clients’ priorities.

This bill would emerge over email and video calls, aided by reporting from news publications and online messaging by advocacy organizations. And those organizations were essential. The plight of minorities in Xinjiang brought together liberal labor rights groups, religious freedom advocates, and conservative China hawks. Lawmakers and staff behind the bill all point to this broad overlapping of political constituencies as the primary reason the bill passed in the end.

“The coalition that mobilized around this was so important,” says the senior Senate Democratic aide. “It made it complicated that you had to get labor on the same side as Republican committee chairs. But the fact that we were able to bring so many people into the process and work toward an outcome was really key. And I don't know if it would’ve been possible if we had an issue other than a forced labor issue in China, because the political climate in D.C. right now is very amenable to tough-on-China stances.”

McGovern recognized that early on. At the event, he emphasized the diverse array of lawmakers and interest groups backing the effort.

“I’m hoping that the U.S. business community is listening carefully. We are together on this,” he said. “And I want to assure people that this is not merely a press release. We intend to push this bill through the various committees, move it to the House floor, move it to the Senate floor for a vote, pass it, and send it to the president for his signature.”

Even as the lawmakers and staff on the commission braced for corporate pushback, they knew they had a couple of important institutional advantages on their side. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has a strong record on human rights in China, stretching back decades, and if anyone was going to allow it to the floor, it would be her. It didn’t hurt, either, that McGovern chairs the powerful House Rules Committee. But important bills often get stalled in Congress or watered down into something meaningless before passing into law.

Rep. Chris Smith, the New Jersey Republican who cosponsored the House version of the forced labor bill alongside McGovern, said as much the day the measure was introduced.

“I’m for scrapping the filibuster at the earliest possible time because it so inhibits good legislation that often passes the House,” Smith told attendees. Those words would ring true months later, when the legislation got held up in the Senate. But the winding road to the bill’s passage was more unpredictable than its sponsors might have imagined at the outset. McGovern remembers he was optimistic about the bill’s odds, though, even if he wasn’t sure about the final outcome.

“I hoped it would pass,” he says.

“I wasn’t doing this for therapy. I was doing this because I wanted to make a difference. I thought what was going on was unconscionable.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.