The longshoremen’s union is threatening to shut down most of the U.S. economy by conducting what would amount to an act of war if a foreign power did it: a blockade of the ports.

But what’s really important is my baby-formula situation.

Oh, I’ll get to the strike, too: This is Bad Economic Ideas week.

Kamala Harris, who wishes to become president of these United States, talks a lot about “price gouging,” a phrase that in the mouth of a politician simply means, “price increases that are politically inconvenient for me.” There isn’t really any such thing as price gouging in an ordinary market—as long as buyers have the option of saying, “No,” sellers do not have the unilateral ability to set prices—and I don’t know whether Harris talks that way because she is an economic ignoramus or because the monopoly that really worries Democrats is the one Republicans are trying to establish in the market for imbecilic populist horse pucky. (Hey, Cleetus: Where’s that Mexico-funded wall you rubes were promised?) It doesn’t really matter which it is—a bit of both, I suspect.

Thing is, I could use some price-gouging right about now.

Like a lot of people in my particular neck of the woods, my family got a “boil water” notice on Monday—flooding from hurricane rains caused water-quality issues. (Short version: Stream and ponds overflow, water runs through agricultural land and such into reservoirs, increasing the possibility of waterborne infections.) Unfortunately, I got the news right after mixing up the enormous batch of baby formula that we need to get through a day with triplet boys. Out went the formula, down the drain. I stopped by Big Lots and picked up the last 20-odd bottles of water before the local stores were stripped entirely.

Right now, there’s not so much as a stray bottle of Dasani in the cooler by the registers at the local Home Depot.

I’m not much use in the kitchen, but I can boil water. We have one of those little electric kettles, which we use to heat up water for warming up bottles of formula and for making Mrs. W’s tea and my Nescafé. (My brother-in-law, whose all-purpose enthusiasm is terrific, has one of those espresso machines that are as complicated to operate as a Gulfstream and cost about as much. I have jars of Nescafé and, if it’s going to be that kind of day, a Mr. Coffee with a great big pot. Is the coffee from the fancy espresso machine really that much better than my instant coffee? Hell, yes it is. But mainly when it’s somebody else going to the trouble.) We make a lot of formula. And I don’t want to boil the water. Yeah, it’s ridiculous to take shockingly expensive organic European frou-frou baby formula and make it even more expensive by using Glaceau Smartwater to make it. But that’s how I want to do it, and I’m willing to pay for the inputs.

But I can’t. Because there’s no water to be bought.

Virginia, where I live, has anti-“price gouging” laws, which are nice and vague: All you have to do to get on the wrong side of the law is offer “any necessary goods and services at an unconscionable price” during an emergency. What is an “unconscionable” price? Basically, whatever the politicians say it is. The result of price controls is pretty much always the same, and it isn’t that you get the goods at the price to which you are accustomed: It is that you can’t get the goods at any price. Supply and demand are real things that exist independent of the law and, when they are out of joint, you get shortages. Dumb laws are one potential cause of that.

I’m not saying that the price-gouging law is the only reason somebody isn’t out there selling gallons of distilled water at the idiotic price I’d be willing to pay for them right now. There are other reasons: Stores may hesitate to mark up prices appropriately during a crisis because they are worried about irritating their customers and subsequently suffering long-term consequences that cost them more than the extra they’d make selling at higher prices—bigger margins on a handful of goods for a few days in limited number of locations probably wouldn’t contribute very much to the bottom line at Kroger or Walmart. Keeping a stockpile of bottled water to sell at higher prices during an emergency would impose warehousing and transportation costs and would pose logistical challenges, since the related emergencies are difficult to predict with any great accuracy. There are transaction costs to changing prices for a few days and then changing them back. Informal prohibitions (corporate inertia, fear of public criticism) may prevent businesses from preparing for emergencies in a way that is socially useful but unpopular. Lots of reasons.

Did you know you can wear out a pretty good electric kettle every six months or so?

As I argued in my conversation with Victoria Holmes when Harris first started talking this nonsense, what we call “price gouging” is not only an acceptable practice but a positively good one. Unusually large profits create incentives for preparing for emergencies and coming up with innovative ways to serve the needs of the public in difficult circumstances. Big corporations are great at that kind of thing—but we typically see it only in their philanthropic activities. The people at Coca-Cola know how to get their product everywhere—everywhere—which comes from years of accumulating local knowledge and building up cooperative relationships, and so, if you are looking to distribute life-saving medication to far-flung villages in Africa, the Coca-Cola network is invaluable. The federal government may not have done a terrific job after Hurricane Katrina, but Walmart did. And philanthropy is great—but if you want real innovation and big changes in the overall material standard of living, nothing drives those like the quest for profit.

Of course, the quest for a bigger payday drives things other than innovation and investment—extortion, for example.

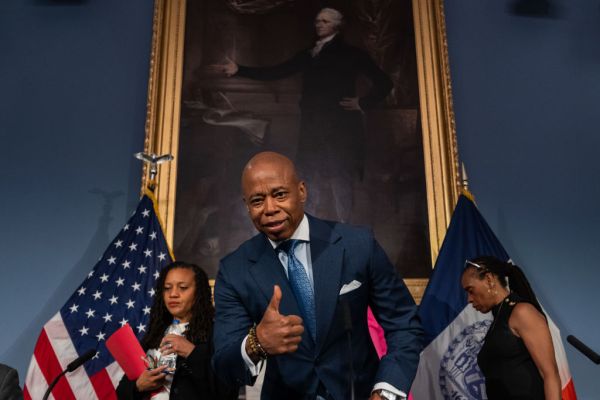

The boss of the longshoremen’s union is threatening to crush the U.S. economy unless companies agree to stop investing in innovation and technology—because that may mean fewer jobs for longshoremen. International Longshoremen’s Association goon-in-chief Harold Daggett is a real piece of work, saying:

When my men hit the streets from Maine to Texas, every single port locked down. You know what’s going to happen? I’ll tell you. First week, be all over the news every night, boom, boom, second week. Guys who sell cars can't sell cars, because the cars ain’t coming in off the ships. They get laid off. Third week, mall starts closing down. They can’t get the goods from China. They can’t sell clothes. They can’t do this. Everything in the United States comes on a ship. They go out of business. Construction workers get laid off because the materials aren’t coming in. The steel’s not coming in. The lumber's not coming in. They lose their job. … I will cripple you, and you have no idea what that means.

I’d like you to imagine those words were spoken by a banker instead of a union boss—a banker who controls all access to credit and funds in the nation’s ports and who therefore has the power to shut them down because he has a monopoly—not a phony-baloney “monopoly” that means he has 45 percent market share in some important business but a real monopoly, one created by the government in the form of a law that says everybody at the ports has to do business with that bank. That kind of monopoly is what the longshoremen’s union has—and what many other unions have, too—a monopoly created by politicians for the benefit of their political clients. Unions are supposed to enjoy the privileges they have because they serve an important public interest.

“I will cripple you.”

Does that sound to you like an organization operating in the public interest?

There used to be a political party—a political movement!—that understood the value of competition in the labor market and the inherent corruption of government-chartered monopolies.

What’s the difference between “price gouging” and union-organizing? If Bill wants $10 a bottle for water, you can go down the street and see what Bob is charging. Unions impose high prices that firms really cannot say “no” to. It is literally an offer you cannot refuse.

The throughline—the necessary thing in both cases—is competition.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.