Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

When Gavin Newsom was waging his primary bid to be California’s governor, he promised voters on the campaign trail in December 2017: “You’re going to have the opportunity to elect the next head of the resistance.” After steamrolling his Democratic and Republican opponents in 2018, Newsom governed with exactly that vision in mind.

At the end of his first year in office, Newsom released a video depicting himself and Donald Trump as cartoon characters in a Mario Kart-style race: While “Donald Trump continued on his horrifying course of attacking our institutions and our fellow Americans,” Newsom said in the video, Newsom was beating Trump by enacting policies like free community college, a moratorium on the death penalty, and tighter gun-control laws. California under his leadership, Newsom said, was “the resistance with results.”

Newsom continued to burnish his resistance credentials over the following years. Amid the Covid lockdowns in April 2020, Newsom said the pandemic was “absolutely” an opportunity for a new progressive era in politics. When the Supreme Court’s Dobbs abortion decision leaked in May 2022, Newsom castigated fellow Democrats for not fighting Republicans hard enough, and at the end of 2023, he positioned himself as a resistance leader by debating Florida GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis on Sean Hannity’s prime-time Fox News show. At the start of 2024, a law signed by Newsom expanded Medicaid in California to all illegal immigrants.

But in the opening months of Trump’s second term, the former self-styled leader of the resistance has made headlines not by fighting Trump but by seeming to retreat from the excesses of progressive politics.

His primary forum has been his new podcast, This Is Gavin Newsom, which debuted on March 6 with special guest Charlie Kirk—the Trump acolyte and leader of the MAGA student-group Turning Point USA. “I love watching your TikTok, which is next level,” Newsom told Kirk, adding that his 13-year-old son was excited when he heard Kirk would be a guest.

The big news out of this first episode was Newsom’s apparent shift to the right on the issue of transgender rights. Letting biologically male athletes who identify as female compete in girls’ and women’s sports is “deeply unfair,” Newsom told Kirk. Even among Newsom’s “own friend cohort, people are saying: ‘The hell is going on? Why aren’t you calling this out? When did this happen?’” Newsom blamed California’s progressive policy on transgender athletes on a law that predated his governorship.

He went on to say that former Vice President Kamala Harris’s position on transgender issues cost her dearly in the 2024 election. The Trump TV ad saying “Trump’s for you; she’s for they/them,” Newsom said, was “devastating. Devastating. Devastating.” (The ad began by showing a clip of the popular radio host Charlemagne tha God saying: “Kamala supports taxpayer-funded sex changes for prisoners.”)

“She didn’t even react to it, which was even more devastating,” Newsom added, before pointing to the lopsided polling on the issue. “Illegal incarcerated individuals getting taxpayer-funded gender reassignment surgeries—that is a 90/10 [issue], not an 80/20.”

Gavin Newsom“Our unity against Trump is not increasing our trust. It’s not helping the Democratic brand.”

The progressive backlash to Newsom was swift. Rep. Sara Jacobs, who represents California’s 51st Congressional District, accused Newsom of “abandoning” transgender kids for “political expediency.” The president of the Human Rights Campaign, the powerful LGBT interest group, accused Newsom of a “betrayal” of “vulnerable communities.”

But the Democratic Party’s problems go far beyond its position on transgender rights, Newsom has contended. He says the party is too insular and needs to learn from successful right-wing communicators, which is why he has hosted MAGA figures like Kirk, Steve Bannon, and Michael Savage on his podcast. “We have to have some humility in terms of where we are,” Newsom said in a March 18 episode with Tim Walz, the Minnesota governor and 2024 Democratic vice presidential nominee. “Our unity against Trump is not increasing our trust. It’s not helping the Democratic brand.” During a March 28 interview on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher, Newsom called the Democratic brand “toxic” and pointed to Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book Abundance, which, Newsom said, “lays out a very damning picture of liberal governance.”

To some, Newsom’s political posturing means one thing.

“Your future is in Iowa,” Maher told Newsom, referring to the all-important presidential caucuses there. “Let’s dispense with the bullshit. … Are you gonna do it or not?”

“I don’t have any grand plans,” replied Newsom.

The California governor has, of course, harbored presidential ambitions from a young age. Newsom’s political patron, former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, recalled in a 2023 interview that the first time Newsom was elected to the board of supervisors in 1998: “One of his buddies proceeded to toast him, ‘Mister mayor, the next time we’ll be toasting this man on his birthday, he’ll be in the White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, and you’re invited.’ That was before he was anything.” As Brown said in 2023, when asked if Newsom has his eyes on the White House: “There is no way in the world anybody who’s ever met him would answer that question any differently. He would like already to be president.”

One big question now is whether Newsom’s post-election pivot is actually helping or hurting those presidential ambitions. Another question is whether he’s actually pivoting at all.

Newsom rises in California politics.

Gavin Newsom grew up in a politically connected San Francisco family. His father was a judge who was close to the Getty family, heirs to an oil fortune that bankrolled Democratic politics in the Bay Area, and his aunt married Nancy Pelosi’s brother-in-law. But Newsom attributes his ambition to his mother, who told him one day while he was having trouble with homework: “It’s O.K. to be average.” Newsom struggled—and still struggles—with dyslexia; his mother’s comment made him recoil. “I said, ‘No! That’s not going to work for me!’” Newsom told the New Yorker in 2018. “That may have been the most damaging thing she ever said to me. It gave me all my drive. I hate her for it—but I love her for it.”

After graduating in 1989 from the University of Santa Clara, he launched a wine-shop and restaurant business bankrolled by the Gettys. In 1996, before turning 30, Newsom got his start in politics when Brown named him to San Francisco’s parking commission; the next year Brown gave Newsom a vacant spot on the board of supervisors.

Newsom’s mother, who was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer and died by assisted suicide in 2002, urged her son on her deathbed to exit politics. As Newsom told the New Yorker: “The night before we gave her the drugs, I cooked her dinner, hard-boiled eggs, and she told me, ‘Get out of politics.’ She was worried about the stress on me.”

Newsom did not heed his mother’s advice. The next year, he found a way to parlay his spot on the board of supervisors to succeeding Brown as mayor—in part by promoting “Care not Cash,” a program to slash maximum cash payments to welfare recipients from $410 to $59 per month while pairing the cuts with more services (such as food and shelter), a position that qualified him as a centrist by the standards of San Francisco politics.

It was during his first year as mayor in 2004 that Newsom accrued his first bit of national fame by veering far to the left of the Democratic Party consensus when he ordered the city to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples in contravention of state law. Newsom's controversial actions resulted in a Harper's Bazaar feature in which he and Kimberly Guilfoyle, his wife at the time, were depicted as the “New Kennedys.” In the splashy photo spread, Newsom and Guilfoyle were sprawled out on a carpet embracing each other.

But courts invalidated the same-sex marriage licenses Newsom’s government granted, and top-level Democrats like Sen. Dianne Feinstein blamed Newsom for Sen. John Kerry’s presidential race loss in November of that year as referenda affirming marriage as a union between a man and a woman passed in every state where the issue made the ballot. On his podcast last month, Newsom said his own father, an “old Irish-Catholic from the west side of San Francisco,” thought he ended his career with his support for same-sex marriage. But Newsom ultimately felt vindicated when the U.S. Supreme Court declared a right to same-sex marriage in 2015 and the public came to overwhelmingly support same-sex marriage.

Now, Newsom is making national headlines yet again by seeming to be out of step with his party on LGBT issues. But on the issue of transgender rights, it’s not clear if Newsom is seeing around a corner—or painting himself into one.

Newsom’s comments about the fundamental unfairness of allowing male athletes who identify as female to compete on female sports teams logically implies the governor would take some executive action or support some legislation to address the injustice. But Newsom recently clarified he doesn’t have any actual policy prescription to address the issue of transgender athletes.

On March 27, U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon sent a letter to Newsom urging him to warn schools they could lose federal funding if they did not implement President Trump’s executive order requiring women’s and girls’ sports teams to be exclusively female. But during an April 2 press conference, Newsom dodged questions about McMahon’s letter and legislation on the matter.

“I haven’t even read it,” Newsom said of McMahon’s letter. Asked about bills voted down in committee the day before in the California Legislature to keep biological males from competing in women’s sports, Newsom said: “I didn’t pay any attention to the committee yesterday.”

He then said he doesn’t have any policy proposal in mind regarding transgender athletes. “We tried to figure out how to balance this. Is there a way to make this work?” Newsom said of the competing interests at play. “We literally were talking to some International Olympic Committee experts … We were trying to figure this out, and couldn’t figure it out. And that’s my point of view—that I just couldn’t figure out how to, quote, unquote, make this fair.”

This is an issue that could dog Newsom in a 2028 Democratic primary and general election—raising questions not only about his ideology but his authenticity and fortitude. It’s hard to see how Newsom would make it through a Democratic primary without saying whether as president he would revoke Trump’s executive order on women’s sports or sign the Equality Act, the sweeping LGBT rights legislation universally backed by Democrats in Congress that goes far beyond the issue of sports. While Newsom hit Kamala Harris for getting on the wrong side of a 90/10 issue by supporting “incarcerated individuals getting taxpayer-funded gender reassignment surgeries,” it’s not clear if he actually opposes or supports that policy in California. Asked if Newsom thinks anything can and should be done to end or limit funding for such surgeries, a Newsom aide simply told The Dispatch: “Like federal prison officials, California prison officials are required by law to provide healthcare.”

According to Garry South, a veteran Democratic operative who ran Newsom’s first campaign for governor in 2010, understanding Newsom’s 2025 comments on transgender rights requires seeing them in the context of his early support of gay marriage. “Newsom is someone who thinks outside the box and kind of prides himself on that,” South told The Dispatch.

While South said he doesn’t know if Newsom will launch a presidential bid, he believes that Newsom’s podcast would help him in a 2028 campaign. “I think the problem that any governor of California, or former governor of California, has running for president is just this sort of animus that exists out there in other states about California,” South said. “We’re LaLa Land. We’re the Left Coast. We’re the land of fruits and nuts.” The podcast, South said, would help Newsom prove he’s not “some kind of a flaky character.”

But other California political observers who have closely followed Newsom’s career say that trying to discern a 2028 political strategy in Newsom’s podcast may be overthinking it. “I don't know that doing what he's doing helps him run for president,” Dan Walters, a California political columnist for nearly six decades, told The Dispatch. “After years of watching this guy, I think he just craves attention.”

“It’s not Clintonesque triangulating,” Bill Whalen of the Stanford-based Hoover Institution told The Dispatch. “He’s getting clicks, he’s getting attention.” U.S. Rep. Kevin Kiley, a Republican who served in the California State Assembly from 2016 to 2022, shared that assessment of Newsom: “He's always shown a high level of interest in doing whatever will get him the most attention at any given moment,” Kiley told The Dispatch.

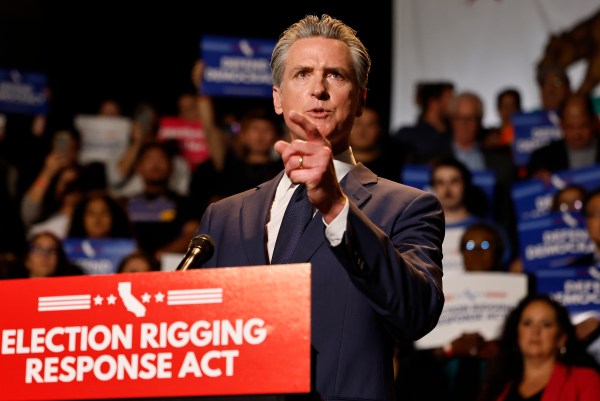

After the 2024 election, Newsom held a special session of the Legislature to “Trump-proof” the state, perhaps another sign he’d try again to lead the anti-Trump resistance. But after the session allocated $25 million for lawsuits against the Trump administration, Newsom’s focus shifted. “He eventually realized this wasn’t quite the vibe this time around, trying to out-compete one another for who can yell the loudest and be the face of the resistance,” Kiley said.

Another possible explanation for Newsom’s political posturing and cozying up to MAGA figures like Charlie Kirk, Steve Bannon, and Michael Savage is that he’s concerned about the Trump administration denying federal funding to the state. “The fires played an important role here,” Whalen said of the devastating wildfires that struck Los Angeles in January. Shortly before he launched his podcast, Newsom sent a request to Congress for $40 billion for wildfire relief, a request that is still pending.

On the April 4 episode of his podcast, Newsom spoke positively of his February 5 meeting with Trump at the White House to discuss the wildfires. “I think I was the first Democrat to sit down in the Oval with Donald Trump, and it was 90-plus minutes, and [White House aides] kept trying to extract us from one another. It was deeply engaging and personal,” Newsom said. “He’s incredibly charismatic.”

"He doesn't want conflict," Newsom added, before blaming the high-conflict Oval Office meeting between Trump and Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky on Vice President J.D. Vance.

When asked to explain Newsom’s more conciliatory approach toward Trump, South, the former Newsom aide, pointed to concerns about federal funding. As governor, Newsom has to “constantly be gauging whether his actions or even his rhetoric are potentially harmful to his own home state in terms of its relationship with the federal government and the Trump administration,” South said. “It’s easier for Bernie Sanders to be running all over the country doing anti-Trump rallies—and God bless him—but, again, he doesn’t run his own state.”

The notion that a politician as ambitious as Newsom might be motivated by something other than his own personal aspirations may be hard to believe, but it would at least provide some logical explanation for his 2025 political posturing.

Positioning for 2028?

It would be one thing for a Democrat with an eye on 2028 to break with his party’s base on one or two politically toxic issues, while simultaneously making sharp contrasts with Trump and Republicans in other areas. But Newsom hasn’t done the latter over the last couple of months. During his podcast with Steve Bannon, for example, Newsom sounded like someone trying to get through Thanksgiving dinner with a politically disagreeable family member without causing too much controversy. When Bannon brought up false claims about the 2020 election, Newsom didn’t challenge him.

Newsom does sometimes take aim at Trump on his podcast, but even then, he often sounds like he’s phoning it in. During the March 18 episode, shortly after President Trump defied a judicial order and sent more than 200 people to a brutal Salvadoran prison without due process under the Alien Enemies Act, Newsom offered a garbled critique:

What more evidence do we need to underscore this notion of, of, of these principles and what’s happened today with the Alien Enemies Act 1700s—and the deportation … and, I mean, this to me, of all the things that has happened during the Trump administration, the notion that you can completely disregard the federal court and literally challenge the court, and for me, just just blatantly in contempt of court. I mean, that's that's the cornerstone of this constitutional democracy.

Perhaps Newsom simply thinks he hasn’t found any solid ground on which to fight Trump. Perhaps he’s trying to placate Trump while tens of billions of federal dollars to his state are at risk. Whatever the case may be, Newsom’s transformation in 2025 from leader of the resistance to passive podcaster has revealed a potential 2028 presidential candidate—and by extension, a party—adrift.

If Newsom has forfeited his title as leader of the resistance, how exactly might he run for president in 2028? It’s hard to see how the California Democrat could reinvent himself as a centrist given several other positions he’s held. For example, Newsom ran for governor on implementing single-payer health-care (but was thwarted by cold, hard math). On his podcast he’s tried to distance himself from the 2020 “defund the police” movement, but just last fall he was on the wrong side of a tough-on-crime referendum that Californians approved by a 37-point margin. And his attempts to blame others for the party’s “woke” turn don’t withstand scrutiny. “Not one person ever in my office has ever used the word Latinx,” Newsom said during his podcast with Kirk. He called the word an “out-of-touch fixation.” But CNN reported that Newsom himself had repeatedly used the word Latinx as governor.

Garry South suggests that if Newsom runs in 2028, he could campaign on his experience of being the governor of the largest state, in terms of both population and economic output. But it’s even harder to see Newsom running as a good-government Democrat than as a centrist.

Consider three California-centric issues that could haunt Newsom on the presidential campaign trail: homelessness, high-speed rail, and housing.

On homelessness, one of Newsom’s first major initiatives as mayor of San Francisco was unveiling a plan in 2004 to end chronic homelessness within 10 years. Twenty-one years later, California remains the worst state in the country for homelessness—accounting for 12 percent of the U.S. population but 50 percent of the unsheltered homeless population, according to Abundance, the book by Klein and Thompson. “To walk the streets of the Tenderloin in San Francisco or Skid Row in Los Angeles, is to stumble into the dystopia tucked amid the plenty of these cities. Tents line the buildings, feces line the sidewalks, needles crunch underfoot,” Klein and Thompson write.

On March 26, Newsom invited Klein on his podcast to discuss the failures of progressive governance. On the issue of high-speed rail, California has been trying and failing to establish for nearly 20 years—and the project is often described as the “train to nowhere.” Newsom told Klein he inherited longstanding problems. “We’re finally laying the tracks,” Newsom told Klein. “We’re gonna get the damn thing done.” But Klein persuasively made the case that the state doesn’t have the $36 billion in funding to complete a line in lightly populated central California, let alone the $110 billion needed to build an actually useful line from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Voters will be able to see the results—or lack thereof—with their own eyes in 2028.

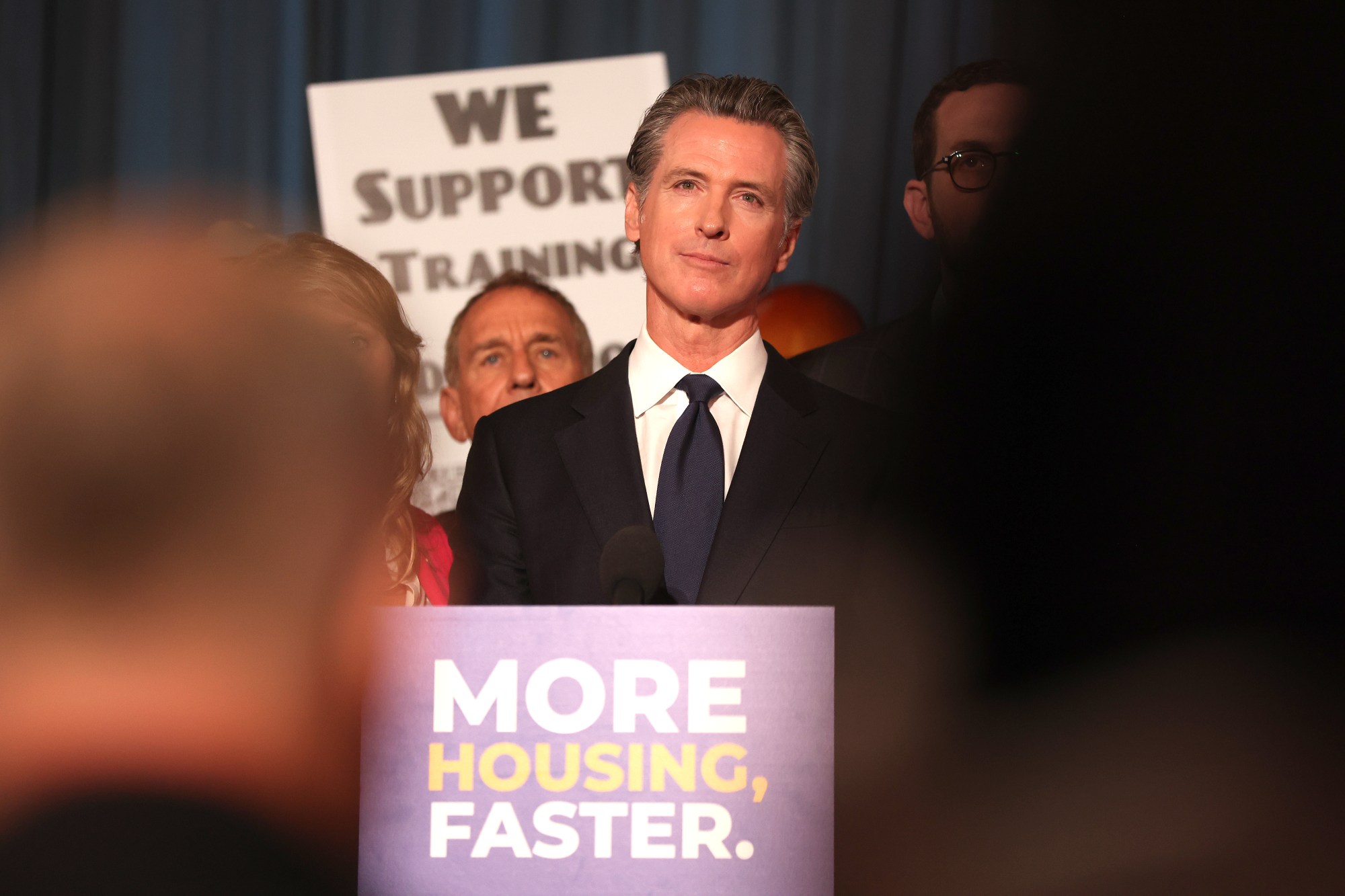

And what of housing affordability more broadly? While running for governor in 2018, Newsom identified housing as a top issue facing Californians, but entering his seventh year of his governorship, he’s failed to improve the quality of life in the state. As Klein and Thompson write: “[California] has the worst homelessness problem in the country. It has the worst housing affordability problem in the country. It trails only Hawaii and Massachusetts in its cost of living. As a result, it is losing hundreds of thousands of people every year to Texas in Arizona.” During his podcast with Klein, Newsom blamed the housing affordability crisis on things like zoning, local government, NIMBYism, and an environmental law dating back to the 1970s. When Newsom cited legislation California has passed during his tenure to address those problems, Klein noted laws to “fast-track” building simply weren’t delivering the promised results, in part due to environmental and other regulatory strings attached: While the city of Houston built 70,000 new dwelling units in one year, San Francisco built just 7,500 new units.

Newsom maintained there was “zero daylight” between Klein’s book and Newsom’s “own self-critique of my own state and my own performance.” Yet when Klein began to discuss how the bureaucratic problems plaguing California were also present in federal legislation signed by Democratic presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden, Newsom rose to Biden’s defense. “I don’t know what the hell more he could have done,” Newsom said of Biden.

“You are more defensive of Biden’s record than your own,” Klein said.

Newsom’s defense of Biden is yet another curious choice for a potential 2028 candidate concerned about how “toxic” the party has become. That toxicity is due in no small part to the unpopularity of Biden, but Newsom’s defense of him is at least one area where he’s remained consistent. “I’ve been spending plenty of time with Joe Biden in public and in private,” Newsom said during his debate with Ron DeSantis in late 2023, insisting Biden was mentally up to the job.

If Newsom can’t run as the courageous leader of the resistance, nor a successful good-government Democrat, nor a savvy centrist, perhaps he can claim the mantle of being a Joe Biden Democrat—right when the party is looking to turn the page on the man who paved the way for the return of Donald Trump.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.