Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

First there was a spark, then there was a conflagration. There is some dispute about who fanned the flames.

Last Monday night’s opening monologue on Jimmy Kimmel Live! generated the spark. For the most part, it was immediately forgotten—except for a sentence about the assignment of political blame for the murder of Charlie Kirk:

“We hit some new lows over the weekend with the MAGA gang desperately trying to characterize this kid who murdered Charlie Kirk as anything other than one of them and doing everything they can to score political points from it,” Kimmel said.

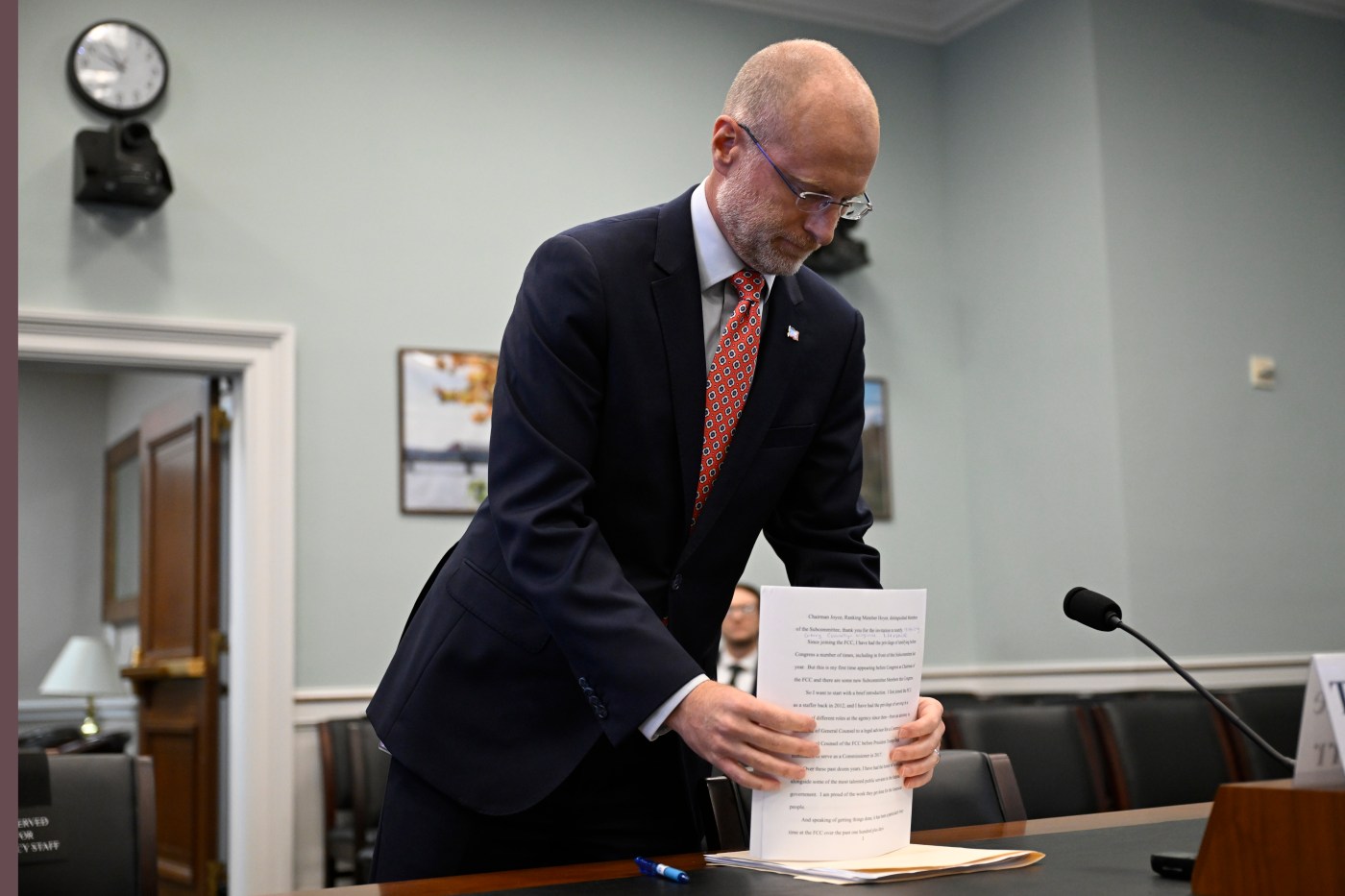

Brendan Carr, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), decided Kimmel’s account of the motives of “the MAGA gang” deserved FCC attention. Two days later, in a conversation with podcaster Benny Johnson, Carr suggested that the FCC might have to “take action” against the broadcasters who featured Kimmel’s show: “I mean, look, we can do this the easy way or the hard way,” Carr said. “These companies can find ways to change conduct to take action on Kimmel or there’s going to be additional work for the FCC ahead.”

Carr’s ill-concealed threat of regulatory action—his allusion to “the hard way”—extended not just to ABC, but its licensed affiliates as well:

There’s action we can take on licensed broadcasters. And, frankly, it’s really sort of past time that a lot of these licensed broadcasters themselves push back on Comcast or Disney and say, listen, we are going to preempt, we’re not going to run Kimmel any more until you straighten this out because we licensed broadcasters are running the possibility of fines or license revocation from the FCC if we continue to run content that ends up being a pattern of news distortion.

Just a few hours after Carr’s remarks, Nexstar—the owner of 32 ABC affiliate stations—announced that Kimmel’s show would be pre-empted “for the foreseeable future.” Shortly after that, Sinclair Broadcast Group—another station combine—followed suit. ABC then announced that it was pulling Kimmel’s show “indefinitely.”

In a subsequent CNBC interview, Carr explained why Kimmel’s remark deserved FCC attention: “It was appearing to directly mislead the American public about a significant fact at probably one of the most significant political events we’ve had in a long time—for the most significant political assassination we’ve seen in a long time.”

On Thursday, a different FCC commissioner made a novel argument about Carr’s statements. In remarks to the Free State Foundation, Commissioner Olivia Trusty suggested that the cancellation of Kimmel’s show was entirely independent of Carr’s remarks. “As we saw yesterday, Nexstar and Sinclair made a business decision to remove or at least suspend the Jimmy Kimmel show because they did not believe it was in the public interest for their viewers,” she said.

What should one make of this?

The FCC’s regulation of broadcasters is nothing new. In the middle of World War II, the Supreme Court determined that the FCC had broad authority to regulate the content of broadcasting. According to National Broadcasting Co., Inc., v. U.S., the FCC’s enabling legislation “puts upon the Commission the burden of determining the composition” of broadcast traffic. Indeed, the court has repeatedly affirmed its justification for the FCC’s immense power over radio and television broadcasters: In a 1969 opinion, Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, the court explained that—because of the scarcity of the broadcast spectrum—the FCC’s license revocations and control over content are consistent with the First Amendment. The court’s theory implies that, because of the scarcity of the spectrum, the FCC is allowed far greater regulatory authority over radio and television broadcasters than over cable TV stations and the internet—because the latter two don't use up the spectrum.

Over its lifetime, the FCC has exercised its authority over broadcasters in a variety of ways. Some of its choices are unexceptionable—for instance, requiring the disclosure of contest rules and of program sponsorship. The commission’s regulations prohibit the broadcast of “hoaxes,” but only if the broadcast involves the propagation of intentionally false information that will directly cause foreseeable and substantial public harm. The commission’s policy toward what it calls “news distortion” raises more substantial First Amendment concerns, but its own regulations require a “compelling showing” of “intentional falsification” before it can act.

As a matter of law, however, intentional falsification involving opinion is impossible. More than 50 years ago, the Supreme Court explained in Gertz v. Welch that, under the First Amendment, “there is no such thing as a false idea.” That means the government cannot ban the expression of opinions (for instance, opinions about whether capitalism is superior to socialism) or theories (such as those about who shot John F. Kennedy or Charlie Kirk). In contrast, sometimes the government can regulate the expression of factual propositions. If I accuse you of assault and battery, perhaps I have defamed you. But if I simply express my own speculative account of things—if I’m engaging in textual interpretation, literary criticism, or some other semiotic pastime—that activity falls under the protections of the First Amendment.

That distinction between fact and opinion is crucial here. According to Carr, Kimmel’s monologue tried “to directly mislead the American public about a significant fact.” But this is pseudolegal gibberish. The factual claim at issue, apparently, is that “the MAGA gang” tried to explain that they had no associations with Kirk’s assassin and to derive political benefit from that explanation. A minor problem for Carr’s account is that fact-checking late-night comedians is self-evidently an absurd way for the FCC to spend its time. A major problem, however, is that Kimmel’s statement is an opinion or a theory, not a statement of fact. That is because there is no way to prove whether Kimmel’s statement about “the MAGA gang” is either true or false: It is only a vague innuendo, not susceptible to verification of such matters as who the gang is or what their motives were. A proposition that necessarily is neither provable nor disprovable cannot be a statement of fact.

Nonetheless, it is easy to believe that Carr doesn’t actually care whether his claim about Kimmel’s monologue is legally well-grounded or not. It is not as if this has all been the subject of a formal dispute in court. It is all too plausible that (as has been reported) the managers of the various broadcasting companies were so alarmed by Carr’s pronouncements that they decided to hedge possible regulatory vulnerability by jettisoning Kimmel’s show. And there is reason to believe Nexstar’s concerns about the “offensive and insensitive” nature of Kimmel’s comments are not its central motivation for throwing him under the bus. Last month, Nexstar announced a $6.2 billion deal to acquire its competitor Tegna—another large TV affiliate enterprise—pending FCC approval. The money at stake makes the value of Jimmy Kimmel Live! look like pocket change.

Nexstar has denied that its decision was influenced by Carr’s remarks or by any considerations about its pending merger. Of course, there are good reasons to expect a conspiracy of silence. Just last year, the Supreme Court decided National Rifle Association v. Vullo, in which it announced that “the First Amendment prohibits government officials from relying on the ‘threat of invoking legal sanctions and other means of coercion . . . to achieve the suppression’ of disfavored speech.” Under Vullo, public officials are disallowed from “using the power of the State to punish or suppress disfavored expression.”

Nexstar has every incentive to avoid any intimation that Carr’s words influenced its decision; as Nexstar waits for the FCC to approve its merger, the last thing its managers want to do is suggest that the commission’s chairman did anything improper or illegal.

Nonetheless, the prospect that the broadcasters were reacting to Carr’s statements cannot be dismissed: The Kimmel cancellations look less like a collection of unrelated events and more like a series of fallen dominoes.

Few of us can be certain about what drives the decisions made in corporate boardrooms, but the prospect of the FCC stifling free expression is alarming. As law professor Richard Peltz-Steele noted, the cancellation of Stephen Colbert’s Late Show suggested that possibility. Did it happen because the FCC might otherwise have scuttled the merger of CBS’s parent Paramount with media company Skydance? Nothing but circumstantial evidence suggested the accuracy of that narrative.

In contrast, one can reasonably interpret Carr’s thuggish bluster about “the easy way or the hard way” as direct evidence of abuse of government power. That is strong evidence, even in the company of Trusty’s smoother and more elegant bluster—namely, her repeated insistence that the broadcasters’ decision was motivated by their own vision of the public interest.

The extraordinary discretion long held by the FCC has now culminated in extraordinary public remarks by the president that openly threaten the corrupt exercise of power. On Thursday, Donald Trump mused aloud about the prospect of future broadcast license revocation. “I would think maybe their license should be taken away,” he said, explaining that “all they do is hit Trump. They’re licensed. They’re not allowed to do that. They’re an arm of the Democrat party.” Revocation decisions “will be up to Brendan Carr.” Brendan Carr is too smart to concede the possibility that the FCC might be used to stifle differences of opinion. Trump, in contrast, is more honest about it.

When the FCC is chaired by an unscrupulous public official who appears eager to misuse its power and urged on by a president who is not even trying to hide his advocacy of the abuse of government power to shut down companies who have expressed disagreement with him—it’s time to rethink (or, better yet, shrink) the powers of the FCC.

“We are in the midst of a massive shift in dynamics in the media ecosystem for lots of reasons, again, including the permission structure that President Trump’s election has provided,” Carr said Thursday. “And I would simply say we’re not done yet with seeing the consequences of that.“

Such statements deserve to be taken both seriously and literally.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.