Scan the headlines of any major media outlet and you’re bound to see a fulsome condemnation of the way state legislatures pick their district boundaries. It’s an interesting phenomenon given the relative monotony of the process over the years. Every decade, state legislatures use the results of the census to redraw congressional and state legislative districts. Sometimes this is done with a divided government, sometimes it is done with one party in charge. In every case, it is done with political considerations in mind.

This had been the case even before adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1787. Partisan apportionment was known to the Founding Fathers—Patrick Henry actually attempted, unsuccessfully, to gerrymander James Madison out of the first Congress.

In 1811, Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry—a signer of the Declaration of Independence—approved a bill adjusting the state's legislative districts to enhance the power of the Democrats and weaken the influence of the Federalist Party. And thus was born “gerrymandering.”

And so it went for the next two centuries. But Democrats have been making the case that it’s a national evil that must be extinguished since 2010, when Republicans swept state and national elections in the aftermath of the Obamacare debacle.

Going into the 2010 elections, Republicans held “trifectas” (governorship and both chambers of state legislatures) in only nine states. After those midterms, they enjoyed total control in 22 states, reaching a high of 26 states in 2018.

Since then, Democrats have filed lawsuit after lawsuit challenging the GOP maps.

It wasn’t a secret that handing state legislatures to Republicans would put them in charge of drawing new district boundaries. In October 2010, Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne noted that a GOP wave could put Republicans in the driver’s seat, writing that a red wave “will have an important impact on the drawing of district lines for the 2012 House elections.”

“The more legislative power the Republicans have, the better their chances of drawing maps that elect more Republicans,” Dionne wrote.

And voters went ahead and put that trust in GOP hands anyway.

One would think that after nearly 250 years, partisan reapportionment would be more widely accepted as the least fraught way of drawing new districts. But politicians, knowing that nobody outside of the occasional editorial board really cares about the issue, stay mum, thinking the issue will burn itself out. But that leads to mass disinformation about what gerrymandering is and what the alternatives would potentially be. And the truth is, the alternatives all come with their own downsides.

I have been writing about partisan reapportionment for over a decade. In 2012, I predicted all of the sturm und drang that we were going to see in the future. I wrote:

Mark it down—in 2022, there will be reporters aghast at the partisanship endemic to the reapportionment process. There will be much hand-wringing and furrowed brows among members of the party out of power. The only good news—they will have forgotten by 2032, when the all the same stories will be written again.

Back in 2001, I even played a hand in crafting maps as a state legislative employee. So I’ll go through a few of the most prominent anti-gerrymandering arguments and why they’re generally bunk.

Gerrymandering locks in permanent majorities.

If Republicans over-gerrymandered congressional districts after the 2010 census, they did a terrible job. In 2018, they lost control of the House of Representatives, and voters gave Democrats control of the House again in 2020.

That is because events and candidates matter just as much as voting projections. As I wrote in 2017, if the state of Wisconsin were considered a congressional district, it would be a solidly blue one: Before 2016, it hadn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since Ronald Reagan’s blowout in 1984.

But in 2016, events took over and the quality of the candidates mattered. A solidly blue presidential state went for Republican Donald Trump as the GOP triumphed in a wave election. Part of this is because voters liked the way Trump fought. Another part is because the voters of the state loathed Hillary Clinton (she was drubbed by Bernie Sanders in the earlier Democratic primary).

As Hillary Flammond counseled in Top Secret!, “Things change, people change, hairstyles change, interest rates fluctuate.” People make their voting choices based on any number of factors, including the quality of candidates, the issues they value the most, and the national mood.

Nothing in politics is static. Yes, you can pack more Republicans in one district and more Democrats in another, but people move, political movements come and go, and both good and terrible candidates run for those seats. Thirteen of Wisconsin's 72 counties have voted for Donald Trump, President Barack Obama twice, Gov. Scott Walker three times, Senate Democrat Tammy Baldwin in 2012 and Senate Republican Ron Johnson in 2016. Voters in these areas are all over the board.

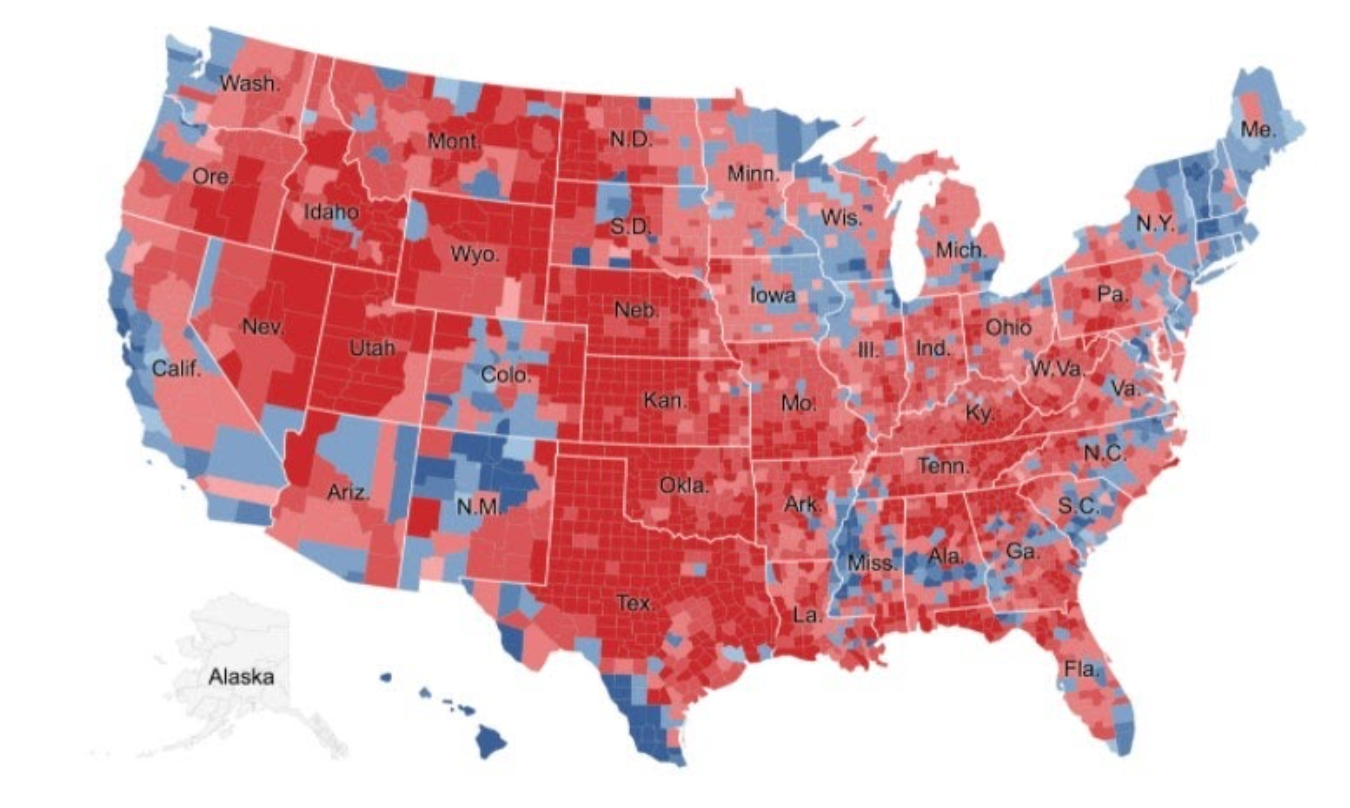

And, of course, there is the difficulty in dividing up seats “fairly,” given the places Republicans and Democrats choose to live. Democrats are typically packed densely into large cities; Republicans tend to live in rural, sparsely populated areas. Look at any presidential election map, like this one from 2020, and America looks like a sea of red:

This makes carving out “fair” districts nearly impossible. Imagine drawing a competitive district in Detroit or Chicago or Washington, D.C., where Democrats win with 90 percent of the vote. This is further compounded by court rulings that protect minority voting rights—segregationists in the South used to dilute the black vote by carving up minority communities; now maps must guarantee a certain number of majority-minority districts in order to protect voting rights for people of color, who overwhelmingly vote for Democrats. Every 10 years Republican maps are subjected to court tests to maintain minority voting power. And virtually every time they pass the test.

But, again, things change. People relocate, traditional parties morph into different parties, and people get elected to Congress that previous generations wouldn’t believe are qualified to hold office.

It’s a Republican dirty trick.

Just this week, the Washington Post reported on a new map from the New York legislature that gave Democrats a huge advantage, yet managed to publish an entire article without the word “gerrymander.” Just weeks before, the g-word made it into the headline of a Washington Post story about Ohio’s GOP-led redistricting. But hundreds of years of evidence has shown us how laughable it is to argue Democrats haven’t done and wouldn’t today do exactly what Republicans have done upon taking control of government.

Take Wisconsin, where in 1982, the Democratic legislature and Republican governor, Lee Sherman Dreyfus, clashed over maps, leaving the matter to a three-judge panel. But that year Dreyfus lost, and in 1983, Democrats and new Gov. Tony Earl wiped the year-old maps clean and redrew them to their liking. It would be another 11 years before Republicans would hold one of the houses of the legislature.

(After the election of 2010, in which Democrats lost control of the Senate, Assembly, and governorship, some Democratic operatives even planned to ram through new maps before Republican Gov. Scott Walker could take over in January.)

“Aha!” say Democrats. Redistricting is different now because we have computers and it is easier for Republicans to carve up districts based on voter data.

This is nonsense. It is generational narcissism to believe that the current crop of legislators are somehow smarter or more devious than those in the past.

Back in 2001, my colleagues used computers to draw maps that are every bit as surgical as the ones drawn 10 years later, only the legislature was divided between Democrats and Republicans. Eventually, the maps were settled by the courts—but each side used GPS software to maximize its own advantage. It was only in 2011, when Republicans had full control of the legislature, that using maps and data became a threat to democracy.

“There is no real difference in the software capability now compared to 1991 (my 1st time),” former legislator Joe Handrick, who used to be in charge of redistricting for the Assembly, wrote to me on Twitter. “The only real difference is now it is free and available to all. The notion that the 2011 maps are the result of huge leaps in technology is pure myth.”

Further, the idea that the 2011 maps were historically gerrymandered isn’t backed up by any data. To prove apportionment bias, Democrats cooked up a formula they called the “efficiency gap,” which, in a lawsuit against Wisconsin Republicans, federal judge William Griesbach called an “unhelpful and dangerously misleading” metric for gauging actual electoral disparities.

As I noted in 2016:

Put simply, the “efficiency gap” measures how many votes a party “wastes”—in theory, the fewer votes a party “wastes,” the easier it is for them to translate their votes into legislative seats. Democrats say Republicans enjoyed an efficiency gap advantage of 13% in 2012 and 10% in 2014.

But even their own standard fails to show anything nefarious was afoot. Democrats glide right by the fact that the maps in place in the previous decade—maps drawn by courts, not by partisans—produced an average efficiency gap of 7.6%, reaching a high of 11.8% in 2006. Yet, miraculously, no lawsuit was forthcoming until Republicans took full control of state government.

Notably, with the maps drawn in 2001, Democrats and Republicans both held control of the Senate and Assembly, respectively, with Republicans gaining huge majorities in 2010. Since the 2011 reapportionment, the GOP majority has held about the same—but Democrats forget to remind everyone that the initial majority was earned under a bipartisan map.

Perhaps the most obnoxious argument Democrats use is to complain that the number of seats they win in the Assembly is disproportional to the total statewide Democrat vs. Republican vote. For instance, they note that in 2012, Republicans received 48.6 percent of the two-party statewide vote share for Assembly candidates and won 60 of the 99 seats in the Wisconsin Assembly. In 2014, the Republican Party received 52 perent of the two-party statewide vote share and won 63 assembly seats.

But just like there is no “national Senate vote,” there is no “statewide Assembly vote.” As I noted above, Democrats are often packed into heavily liberal geographic areas, where Republicans can’t even field a candidate. There are no commensurate areas that are that heavily Republican. Thus, if the GOP fields fewer candidates, the Democrats’ share of the total state vote will be artificially high. (Imagine, for instance, what the “national Senate vote” would look like if, say, no Republican ran for the Senate from California.)

Further evidence that it’s not just Republican trickery is the fact that Republicans frequently sue Democrats for their overtly partisan gerrymandering. Republicans have sued Democrats in states like Maryland, Nevada, and New Jersey alleging excessive partisanship in their apportionment process. All total, the Brennan Center found partisan gerrymandering lawsuits in 13 states and in five states, suits were filed by Republicans.

What is the remedy?

If you’ve gotten to this point and your reaction is “legislators shouldn’t pick their own voters,” then what is the remedy? How would we fix it?

Gerrymandering opponents offer nonpartisan redistricting boards as the way to guarantee fair maps. Some states have even set up laughable processes for citizens to submit their own maps, each of which will be read by fewer people than Snooki’s autobiography.

The problem, of course, is that “nonpartisan” boards are never devoid of politics. When California enacted a nonpartisan redistricting board, it didn’t take long for it to come under attack for overt partisanship.

Attorney Rick Esenberg put it well here:

"Non-partisan" solutions rarely remain non-partisan and often succeed only in driving the politics underground. It is notoriously difficult to drive the politics out of something that is inherently political.”

The other relief Democrats seek is for courts to micromanage the reapportionment process, a power which is explicitly given to legislatures in the U.S. Constitution. Democrats argue gerrymandering is a violation of their 14th Amendment protections, as packing people into like-minded districts dilutes their “one person, one vote” rights.

Thus, the maps have been challenged on partisan grounds, even though such partisanship has never been the basis for a successful challenge in the U.S. Supreme Court. Allowing challenges to partisan apportionment demands that judges all over America suddenly become political pundits, determining which candidate should "rightfully" win each legislative seat in every state.

Fortunately, in 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a lawsuit seeking to strike down partisan redistricting, deeming it outside their purview.

"We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts," Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the 5-4 conservative majority. "Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions."

“Excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust,” he wrote. “But the fact that such gerrymandering is incompatible with democratic principles does not mean that the solution lies with the federal judiciary.”

Roberts added that it would be impossible for the court to determine a workable standard to answer “the original unanswerable question (How much political motivation and effect is too much?).”

Roberts conceded that if partisan gerrymandering is getting out of control, there are legislative remedies. Laws can be passed. State constitutions can be amended. But the courts should not be responsible for picking legislators based on shady calculations that try to guess prospective voter behavior.

Would it be preferable if there were some magical system where legislative districts were drawn in a fairer, more understandable way? Of course it would. But this is the system we have—a system that has served America well since the 18th century. If you’re worried about the fairness of the apportionment process now, just wait until unelected, unaccountable bureaucrats are dictating your choices in the ballot box.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.