Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

Weeks before the 1984 presidential election, a writer excoriated the Democratic Party’s nominee, Walter Mondale, for his “capture” by “special interests” like labor unions and domestic industry to promote devastating protectionist trade policies.

“Although protectionism may create jobs in some industries, these gains will be largely, or perhaps completely, offset by a reduction of jobs in other industries because of protectionism's ripple effects,” the writer argued in an op-ed for the Christian Science Monitor, highlighting the negative effects on America’s farmers, exporters, and defense industry. The writer lambasted America’s already existing “dizzying array of tariffs, quotas, voluntary export restraints, and other nontariff barriers on everything from steel, textiles, and shoes to motorbikes and machine tools” and suggested Mondale’s support for legislation requiring automobiles sold in the United States to have a high percentage of American parts and labor participation would “further skew, rather than make more fair, America's income distribution.”

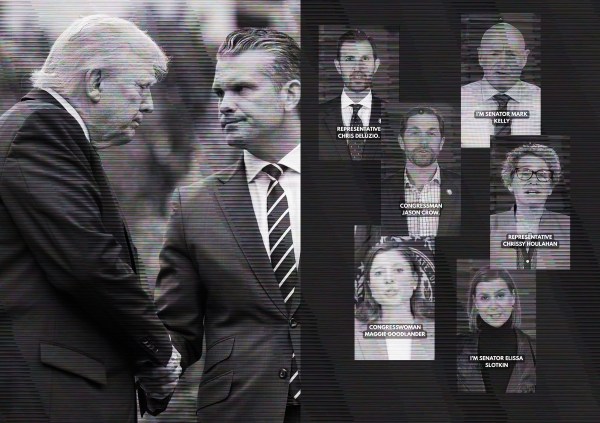

That writer was none other than Peter Navarro, a 35-year-old Harvard Ph.D. student who is now the chief and most strident adviser to President Donald Trump on behalf of the most damaging protectionist trade policies of all: tariffs. Beyond the 180-degree switch in Navarro’s views, a lot of the politics of trade have changed over the last four decades, including the fact that it’s the Republican Party, fully behind Trump, that is more closely associated with trade protectionism than the Democratic Party.

Just as it’s no longer Ronald Reagan’s GOP when it comes to foreign policy, constitutionalism, and free-marketism, it’s no longer the pro-protectionist Democratic Party of Mondale, Dick Gephardt, and organized labor.

Or is it?

Democrats, it seems, are having a public conversation about how exactly the party should respond to the Trump administration’s let-’er-rip tariff policy. If they’re not careful, it could metastasize into a full-blown intra-party debate, the winner of which could determine how Democrats develop their trade and economic policy for the 2028 elections and beyond.

The initial reaction to Trump’s tariff actions from leading Democrats has been reflexively oppositional. There was Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s reaction on social media last week to one of Trump’s boastful claims (amid a disastrous stock-market selloff in response to the tariffs) that the president’s trade policy would lead to bigger prosperity. “And the rich get richer,” Schumer tweeted, seeming not to take into account that everyone at the moment was getting demonstrably poorer. And last month as stocks began to falter following Trump’s first rounds of tariffs, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz claimed he was keeping an eye on the falling price of Tesla stock to “give him a little boost.” (Tesla, of course, is the electric car company owned by Trump ally and special government employee Elon Musk.)

Other Democrats are making more substantive challenges to Trump, primarily focused on the effect of these tariffs on the costs of goods and services. Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker has cast Trump’s tariffs as a “tax on working families” and a threat to his state’s agricultural industry, while Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro similarly characterized the administration’s policies as a price-raising blunder.

“This is super simple. Donald Trump pressed a button, raised costs, started a trade war with our allies, which is going to further raise costs on the American people, and it’s going to make people’s lives worse,” Shapiro told MSNBC host Stephanie Ruhle last week.

But there are still some of the old Mondale school in the Democratic Party, such as Rep. Jared Golden of Maine, who has won his rural district four times in a row despite Trump carrying the district in both 2020 and 2024. Golden has been cautiously supportive of Trump’s tariff policies, saying last week he was “pleased” with the president’s agenda so far and reiterating his support even after Trump paused the reciprocal tariff schedule on Wednesday.

“I’m happy he’s left the 10 percent global tariff in place,” Golden told my colleague Charles Hilu on Capitol Hill. “I’m happy he’s left the higher tariffs on China in place.”

Golden is not the only Democrat talking up the positives of tariffs. Take Gretchen Whitmer, the two-term Democratic governor of Michigan who, like Pritzker and Shapiro, is a potential contender for her party’s nomination for president in three years. She also hails from the home state of America’s legacy auto industry where the politics of tariffs and trade play a little differently than many other parts of the country. To that end, Whitmer visited Washington this week not to bury Trump’s tariffs but to praise, well, the idea, at least. In a speech Wednesday at the Council on Foreign Relations, she argued for a more measured and “strategic” employment of tariffs than what the Trump administration has done so far.

“As I’ve said before, I’m not against tariffs outright, but it is a blunt tool. You can’t just pull out the tariff hammer to swing at every problem without a clear, defined end goal,” she said. “Strategic reindustrialization must be a bipartisan project that spans multiple administrations.”

For a Democratic base looking to its high-profile leaders to take on Trump directly, Whitmer’s remarks were jarring. Bipartisan? Working with Republicans? Arguing that Democrats should offer a kinder, gentler version of Trump’s trade policy? (It didn’t help that Whitmer made an ill-advised stop at the White House and was unwillingly roped into a photo-op for Trump that her would-be Democratic primary opponents will be thrilled to use against her in a couple years.)

It was the substance of Whitmer’s speech, however, that prompted a direct response from Whitmer’s fellow Democratic governor, Jared Polis of Colorado.

“The ‘tariff hammer’ winds up hitting your own hand rather than the nail,” he tweeted Wednesday. “Tariffs are bad outright because they lead to higher prices and destroy American manufacturing. Trade is inherently good because both parties emerge better off from a consensual transaction.”

As nationally known Democrats go, Polis, with his western libertarianism, is more than a little heterodox—very few would go as far as he does in sounding like an out-and-out free trader. But there is tension between the Whitmer/Golden approach and the Polis view. Do Democrats seize the opportunity to be the party of trade liberalization now that Republicans have abandoned the concept? Or will they run as the smarter, better, more “strategic” trade warriors, unwilling to cede the issue of tariffs to the GOP when Sen. Bernie Sanders, a dyed-in-the-wool protectionist, is still commanding large crowds?

“Bernie having his finger on the pulse of this issue and his opposition to NAFTA was what won him the edge against Hillary in the 2016 Michigan primary,” is how one Democratic strategist familiar with the Wolverine State put it to me. “And that sentiment has remained the same.”

Perhaps, but the timing of Whitmer’s trade triangulation couldn’t have been worse. Between the Democratic Party’s thirst for more wins against Trump and the ongoing collapse of the financial markets in response to Trump’s actions, perhaps Pritzker and Shapiro have the savviest approach: highlight how Trump’s policies are hurting Americans, focusing on real, tangible economic conditions like prices, and leaving the more philosophical debates about trade policy for later.

“I’d counsel clients to keep the focus on Trump’s erratic and compulsive governing approach,” Dale Strother, a veteran Democratic operative, told me. “I’d make it clear Trump’s governing style is akin to a drunk driver weaving down the road barely missing ditches. Make it about Trump and increased costs of everyday items.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.