Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

A few years ago, the Babylon Bee proposed a new model of the crockpot: “The Baptist.” The premise? “The Jacuzzi-sized Crock-Pot can prepare enough chili, stew, or questionably cooked chicken to feed thousands” and it is “large enough to carry out a full-immersion baptism.” Touché, Babylon Bee, touché.

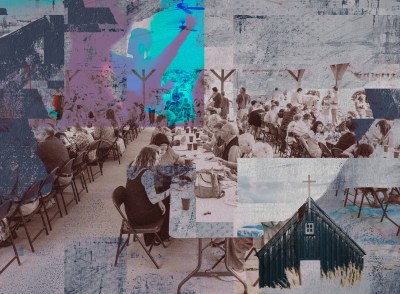

For as much as church-going Christians love to joke about church potlucks and what counts as a “vegetable” for their purposes (to be quite clear, macaroni and cheese belongs on the vegetable table, thankyouverymuch), they are a tangible way Christians show love to one another. Preparing food for these gatherings is inextricably connected to thinking about others in the congregation, praying for their needs, and loving them in this mundane yet concrete way. In our decidedly narcissistic culture (paging Christopher Lasch), church potlucks and meal trains are remarkably premodern and lovely ways of building community and fostering connections. Behold, the church is still putting on what second-century believers referred to as”love feasts.”

My church has a half-hour-long coffee and cookie fellowship every Sunday between Sunday School and worship. It may sound relatively simple, and I suppose it generally is. Someone brews coffee, and a couple of people bring baked goods. Yet, nothing is simple in a fallen world. Some members of the congregation may have food allergies, sensitivities, and illnesses. Several members (including my husband) have Celiac disease, an incurable autoimmune condition that treats gluten as poison to the body. Others have diabetes. A member who attended years ago could not consume any grain. So hard-boiled eggs and cheese cubes are now regular offerings, and week after week, the church ensures no one is left out. Every coffee hour or church potluck, something is set apart and labeled for every dietary need, no matter how bizarre.

There is a reason the early church referred to such potlucks as “love feasts”—none of this could happen without love. When my then 5-year-old overly enthusiastically enjoyed a particular dessert one Sunday, a few weeks later the friend who had prepared it made it again—with my child in mind. In this way, the preparation of food for communal gatherings is something not just practical but prayerful, as it brings us closer to seeing someone as they are in God’s eyes—unconditionally precious, lovely, and possessing genuine opinions, preferences, and needs. Indeed, sometimes people will say to someone outright: “I prayed for you as I was baking.”

But the hospitality of church potlucks extends far beyond the doors of the church and Sunday mornings. At any given moment, a meal train or several are connecting church members to a person or family in need—someone housebound because of illness, or a family grieving the loss of a loved one. Then there are more joyful reasons for these meal trains, such as the arrival of a new baby. These are my absolute favorite occasions, I confess. Rejoicing with families over new arrivals and sharing the table with them through bringing a meal is a delight. Each time I do, I’m reminded of the many meals my family has received over the years, such as when our younger two children were born or when we experienced a devastating pregnancy loss. Each time, we felt loved, seen, and cherished as part of a community that extended beyond our household. I still remember specific people and meals and conversations as a result. “I prayed for you as I was cooking” remains a constant refrain.

So why might this matter for American society at large, as opposed to just church-going folk? It is a good question to ask—and answering it shows certain losses in our society. I taught ancient history to college students for 15 years, and one of the most difficult concepts to explain was historical significance. Why is a particular event or person or concept important? Often the easiest way to explain it was to invite students to imagine a world without the idea or person in question. What might our society look like without church potlucks or meal trains and the general philosophy of hospitality?

The answer, as it happens, is right in front of us.

Those without a community with whom to share gatherings lose an opportunity to serve and be served in a way that is no less transcendent than physical. In theory, hospitality of the sort I have experienced in churches does not have to be particular to a religious community. Anyone can make coffee and bake muffins and have friends over. Anyone can decide to start a meal train for a friend who just had a baby. And I am sure some people do. Still, outside of churched circles, such habits are decidedly uncommon. Worse yet, they seem strange. A secular academic once remarked to a friend of mine about a (Christian) candidate his department had interviewed and did not hire, saying something to the effect of, “We knew we couldn’t hire a weirdo who would have students over to his house to have dinner with his family.” The comment reflects an increasingly common view. Except, in fact, this view is nothing new.

When early Christians gathered together—free and slave, men and women—to eat the same food and drink the same drinks, as we hear of them doing already in the book of Acts, they were breaking fundamental social taboos of the Roman world. In a Roman banquet, seating arrangements were decided by social rank. Food and drink were then served by rank as well, from best to worst–meaning the highest ranked were served first, and they also got the best quality of food and drink. Roman society was hierarchical and well-ordered: Every person knew his or her place. The most serious criticism we hear of the Lord’s Supper in the New Testament—Paul blasting the Corinthians who allowed some to get drunk and others to go hungry during the communal meal—is describing what would have been perfectly typical behavior for a Roman feast. But it was not what should happen at the Christian love feast.

Indeed, the original Greek word for fellowship that occurs in the New Testament—koinonia—bears hints of this sense of otherworldly community already. Originally a political term that occurs in such Greek political writers as Aristotle, koinonia referred to the obligations citizens had for their city-state. A related term, koinon, referred to military and diplomatic federations of states. The root meaning always denoted something shared, held in common. So we see the idea of church fellowship as the sharing of meals and companionship together. But, of course, there is a difference between the world of the Greek city-states and the Roman Empire that eventually absorbed them. Among other political terms the church had borrowed from the Greek city-states is the very word we use for church—ekklesia, which originally meant citizen assemblies. Except, only adult males who could afford their own armor could be members of these assemblies, just as they alone were part of the original koinonia. When the church adopted these terms to refer to its gatherings of all people—men and women, slave and free—it was a not-so-subtle proclamation: Our kingdom is not of this world.

Third-century apologist Tertullian explained the basics of these gatherings of Christian fellowship in his Apology, a defense of Christianity and of Christians he wrote for Romans bent on persecuting the church. The “peculiarities of the Christian society” include beginning and ending the feast with prayer, serving modest food, and not over-indulging unlike (he notes) feasts in honor of the pagan gods like Dionysus. Once concluded, these feasts send people out equipped in virtues that make them better Roman citizens: “We go from it, not like troops of mischief-doers, nor bands of vagabonds, nor to break out into licentious acts, but to have as much care of our modesty and chastity as if we had been at a school of virtue rather than a banquet.”

The Christian occasions of fellowship, in other words, form their participants to be not only better believers in their own faith but also better members of society—and therefore better Roman citizens. Tertullian does not shy from stating this last point outright. Christian hospitality is a radical school of the virtues rather than an occasion of overindulgence. All in all, the Roman Empire was a better place for having Christians in it.

In making these arguments at great length, Tertullian was responding to real accusations, some of which survive. A few decades earlier, in the second century A.D., Roman philosopher Celsus wrote a treatise, now lost, against Christianity. We know it from extensive quotations by Origen, the Christian thinker who wrote a detailed response. Celsus, it appears, wielded a number of arguments against Christians, whom he considered the enemies of the Roman order. But the argument that particularly stands out is the one against Christian hospitality. What are these “love feasts” they speak of, he asks. Could this be anything other than secret debauchery or scheming against the empire? For Celsus, just as for some secular observers today, ordinary Christian hospitality that welcomes all guests as equally worthy and precious seems scandalous, inappropriate, out of the realm of respectability. The results of such a view are depressing—quite literally.

In his 2019 book, Alienated America, journalist Tim Carney bemoaned the isolation and desperation of too many people in our society. Those lacking church connections were particularly at risk for such isolation and its worst consequences. Carney noted the rise of deaths of despair by tracking communities with high rates of alcoholism and drug overdose deaths. And this was before the COVID lockdown of 2020 and before the U.S. surgeon general declared loneliness an epidemic with deadly consequences. The situation has only gotten worse since.

We are an isolated society of isolated people. A Pew Research Center survey in 2023 reported that 8 percent of Americans “have no close friends.” If you think this is sad but not too bad, a 2024 report from the Survey Center on American Life stated that America is in the midst of a friendship recession. The recession, the report noted, affected those without a college degree worst of all: “Roughly one in four (24 percent) Americans with a high school education or less report having no close friends, compared to only 10 percent of college graduates.”

But I wonder also about the religious dimension of this lack of friends. Where else but in church might you meet people who feel an unconditional conviction that you are a brother or sister, and who want to feel your joys and sorrows—and celebrate them with food, when applicable? Where else, in these days when 5 percent of Americans spend even Thanksgiving alone, increasingly more Americans work remotely, and friends too often communicate with texts and emojis, would you get to break bread (gluten-free if needed) on a regular basis with people who know you deeply, are glad you are there with them, and would notice your absence whenever you are not there?

And what other structures might call you to think of others frequently ahead of yourself? Church hospitality, especially meal trains, requires an awareness of others’ needs, sorrows, and weaknesses, and their incorporation into our own busy days. This process requires knowing—and thinking actively—that yes, this family just had a new baby, which means they need prayers and meals. And yes, this person in church just had major surgery and will be homebound for the next month and will therefore welcome not only meals but visitors who stay and talk. Such a way of thinking is as radical today as it was in Tertullian’s day.

Needless to say, church potlucks and meal trains cannot solve every problem related to loneliness and isolation. Hospitality, while good, is not the ultimate good. Still, church hospitality—and churches in general—do much more good than many people imagine for the holistic health of individuals in a society where every practical structure is directed at isolating individuals from other human beings (although not from machines or bots). This hospitality is a beautiful reminder of a truth confirmed by both theologians and modern social scientists alike: We have been created for community. We do not belong to ourselves alone, and this is good.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.