“China is going to eat our lunch? Come on, man,” scoffed then-presidential candidate Joe Biden in 2019. Two years later, as president, Biden declared, “The Chinese are eating our lunch. They’re eating our lunch, economically. They’re investing hundreds of billions of dollars in research and development. … We got to compete.”

Mario Cuomo famously said that politicians “campaign in poetry, but govern in prose.” But in this case, the poet was closer to the mark. The Chinese economic rocket looks to be running out of fuel.

Chinese economic statistics have never been entirely reliable, but the last reported number for urban youth unemployment we have is 21.3 percent (it may actually be closer to 50 percent). One sign it will get worse: China recently announced it will no longer be publishing youth unemployment—or consumer confidence—-numbers.

China is also facing a ripening debt crisis and potential deflationary spiral. For decades, the Chinese government has encouraged real estate speculation and overinvestment. Millions of Chinese small investors and families responded by putting their eggs in the housing basket, which fueled massive bubbles, soaring home prices, and crushing increases in debt. Countless skyscrapers, airports, highways, even whole cities, are little more than white elephants thanks to state-directed overbuilding.

Now, the housing sector—roughly a quarter of China’s economy—is cratering. Falling prices, construction industry bankruptcies, and slower growth are scaring consumers out of spending and raising concerns about deflation.

Foreign investment in China is drying up as investors see even more contraction on the horizon and foreign firms—and even Chinese ones—move their supply chains elsewhere.

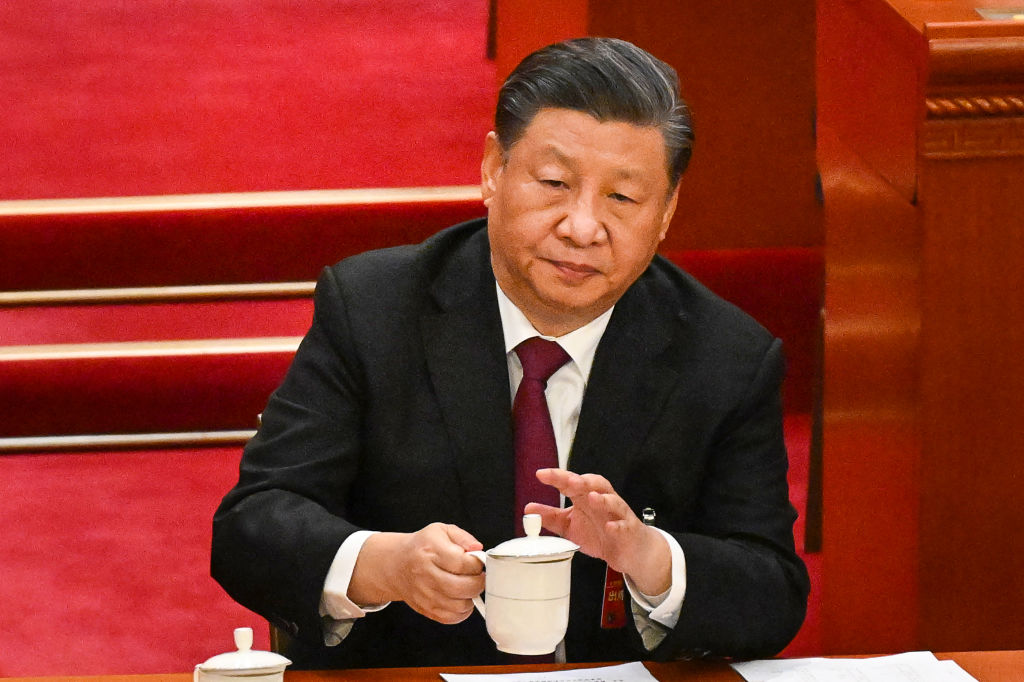

Xi Jinping, China’s proudly authoritarian president-for-life, has responded to these and other economic challenges by insisting that everyone should toughen up in the name of national “rejuvenation.” Young people need to “abandon arrogance and pampering” and embrace the Maoist spirit of self-sacrifice, which is why the state cracked down on decadent video-game playing. “Eat bitterness” he tells college grads while banning private test-tutoring, throwing many educated young people out of work in the name of social equality.

Xi believes China is rich enough to do what it needs to do—supplant the United States as the global leader and become an imperial hegemon in, for starters, its own neighborhood. Politically enforced internal discipline, military expansion, and consolidation of political and economic power in his hands is more important than additional economic growth. And by implementing such measures, he all but assures that the economy will get worse. Markets need reliable information and freedom to function, and information is joining economic freedom in lock-up.

In the 1990s, the “neoliberal” consensus was that economic liberalization would push China toward political liberalization. Today, that consensus is out of favor just about everywhere. But it’s increasingly clear that Xi agrees with that view—he just thinks political liberalization is bad. Which is why he’s so willing to tolerate economic contraction in exchange for Spartanism with Chinese characteristics.

It’s no coincidence that Biden claimed China was eating our lunch when he wanted to get his “American Jobs Plan” approved. In America, the argument for state-directed economic planning is always made in the language of “competitiveness.”

According to the simplistic binary logic of “competitiveness,” China’s economic woes should be good news for America. This zero-sum view sees GDP gains as points on a scoreboard, where our “wins” are their “losses.” But it doesn’t work that way. Contrary to a lot of bipartisan talking points, China getting richer didn’t make America poorer. And if China’s economy implodes, our economy will suffer as a result.

Policymakers have been struggling to define the Chinese challenge. Is it merely a competitor or a strategic adversary? The Biden administration has been clear that it would prefer to keep China an economic competitor and not a strategic or military adversary. And they’ve taken a number of praiseworthy steps to prevent the latter.

But it’s important to get the causation right. The Chinese threat is geopolitically and ideologically driven, not economically. Constraining China’s access to sensitive technology and buttressing alliances in the region is necessary not because of China’s money, but because of what the Chinese regime wants to buy with it. A rich, democratic, China would be good for everyone, especially China.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.