Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

Over the past dozen years, American scholars have typically characterized China as a purely obstructive, or destructive, force in international affairs—one that has sought to undermine a liberal “rules-based” world order. According to the Princeton political theorist John Ikenberry, China’s leaders “don’t have an alternative international order.” They can “do damage to the system,” they can be “spoilers,” but they “can’t really be in the game of defining the next system.” Tufts’ Michael Beckley and Johns Hopkins’ Hal Brands claim that the “heart of Chinese strategy today” is “democracy prevention.” And Johns Hopkins’ Jessica Chen Weiss asserts that “China has no coherent, universal ideology.”

But is it accurate to see China as a mere wrecker of global order? Is it true that China has no world vision of its own?

Through a Cold War lens, Chinese political ideology equated with communism. The fall of communism therefore meant the collapse of China’s guiding worldview. And so it is easy to see today’s state-capitalist China as ideologically rudderless. Yet by far the most fashionable contemporary political and legal thought in China is, in fact, well grounded in readily identifiable Western theory. It is simply not the Kantian liberal theory that the American political class was weaned on, consciously or otherwise—the sort underlying Francis Fukuyama’s famous declaration in 1989, the year the Berlin Wall fell, that American-style liberal democracy represented “The End of History,” or the culmination of mankind’s three millennia of experimentation with political governance.

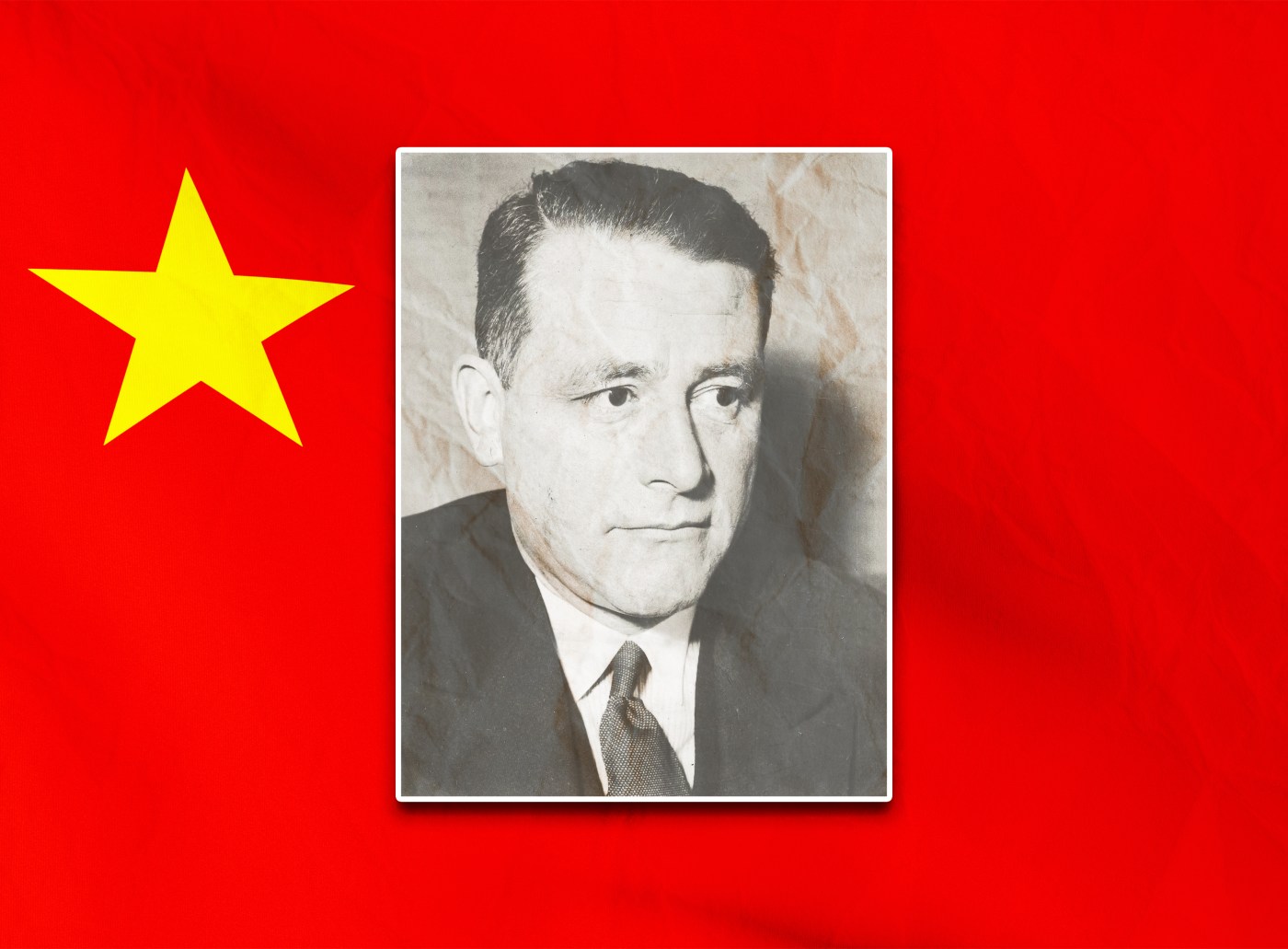

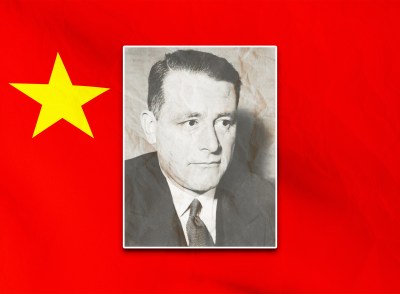

In Chinese universities, Karl Marx remains foundational, of course, and the study of his thought remains mandatory. Yet over the past 20 years, another German writer has helped to shape China’s ideological development. Improbably, he was an anti-Communist scholar and polemicist, a man who became known, and notorious, worldwide as Hitler’s “crown jurist.” His name is Carl Schmitt.

To be sure, followers of Xi Jinping’s pronouncements will not find reference to Schmitt, or indeed to the thought of any other favored Western political thinkers—no more than students of recent American presidents will find references to Locke or Montesquieu or Fukuyama. The job of identifying useful foundational thought is, everywhere, left to public intellectuals, who create the philosophical scaffolding for critiquing and justifying political actions. China is no different than the United States in this regard, save that its one-party system circumscribes the width and height of the scaffolding that may be erected safely—that is, without risk of harm to one’s career and life prospects. For Chinese scholars, Schmitt uniquely fits the bill.

Born to a devout lower-middle-class Catholic family in predominantly Protestant Plettenberg, Westphalia, in 1888, Schmitt rose to prominence as an incisive and deeply read scholar of constitutional law and European political history in the 1920s. His analytical thinking was shaped by bitterness and distress over Germany’s political and economic struggles under the post-World War I Weimar Republic—struggles that he blamed on a flawed liberal constitution that promoted paralyzing and divisive parliamentary proceduralism over the shaping of national unity under decisive leadership.

Schmitt opposed Hitler and the National Socialists until they actually came to power in 1933, at which point he joined the party and radically restated his views to accommodate its racial dogma and, in particular, its violent antisemitism. He defended Hitler’s execution of dozens of rivals after the so-called Night of the Long Knives in 1934, and recast German law in racial terms, arguing that the nation’s jurisprudence needed to be purged of Jews and cosmopolitan Jewish influence. But by 1936, Nazi SS and legal ideologues under Heinrich Himmler came to see Schmitt as an untrustworthy opportunist, and he himself was purged from the leading party legal organizations.

After the war, Schmitt avoided prosecution at Nuremberg by arguing, successfully enough to make conviction uncertain, that he had been a mere legal theorist acting at the margins of the regime. He later attacked the trials as “victor’s justice,” and refused to cooperate with the Allies’ denazification program. This led to his barring from German university posts, although he continued to write and speak publicly until his death four decades later—in 1985, at age 96.

Schmitt’s wartime status as, in effect, the devil’s advocate naturally dampened his global academic following. For his analysis of liberal democracy’s weaknesses and vulnerabilities, however, he remains required reading. Here are some of the main arguments for which he is renowned.

First, “democracy” for Schmitt meant the unification of the will of the leader with that of a people. “Liberalism,” with its fetish for debate and reliance on the fairy tale that “law” could actually rule, was a barrier to this unification.

Second, “sovereignty” lay not in applying constitutional norms, but in leaders taking and implementing concrete decisions. In his most widely cited dictum, “The sovereign is he who decides on the exception”—that is, the person or body capable of declaring that the norms do not apply in a given exigent circumstance, and then acting outside of them.

Third, politics was inherently adversarial, and all states necessarily had “enemies,” understood as out-groups who represented a threat or potential threat. Whatever principles a state stood for—whether “freedom” or “the great nation of the whositwhats”—there would necessarily exist other states which stood for different principles, or different understandings of them.

Fourth, the advent of American-inspired “universal law” after World War II, though ostensibly promulgated to promote world peace, actually fueled existential total wars because of the implication that those who contravened it were outside of humanity and needed to be destroyed in its defense.

Fifth, a stable international order required regions under the stewardship of a dominant power, such as the Western Hemisphere under America’s “Monroe Doctrine,” which balanced each other out. Schmitt used this idea to justify Hitler’s efforts to “unify” Europe.

So, of what relevance is Carl Schmitt to today’s China? Over the past 20 years, both Chinese and Western followers of the country’s politics have noted the rise of “Schmitt fever” among Chinese intellectuals. This phenomenon is apparent in the graphic below, which tracks the soaring scholarly interest in Schmitt since 2003.

Why do Chinese scholars see engagement with Schmitt’s work as important? Since the late (pre-WWI) Qing dynasty, Chinese elites have considered the coopting of Western intellectual thought as an essential element in securing legitimacy abroad and commanding respect in a global order dominated by Western powers. The People’s Republic of China’s founding Marxist-Leninist ideology was itself, of course, a Western import, despite the fact that the Chinese Communist Party’s agrarian roots fit poorly with it. Chinese scholars have since proved their usefulness to the party by continuously providing it with new legal and intellectual bases for its ever-evolving economic and political priorities. By strategically appropriating copacetic Western thought on sovereignty, centralized authority, and state-led economic development, China’s rulers can confidently deflect charges that they are engaged in mere authoritarian apologetics.

An intense interest has thus emerged in laying a historically grounded political and legal framework for asserting a rising China’s rights on the global stage—and Schmitt is the perfect thinker to aid in the task. As a Western anti-liberal, he is a powerful foil to the Fukuyamist doctrine that liberal democracy has unique legitimacy and resilience as a universal organizing political framework.

Schmitt began to attract notable Chinese intellectual attention in the late 1980s, in the context of growing interest in so-called neoauthoritarianism—a contemporary form of governance that combines centralized political control with selective use of market-oriented reforms. In 1987, politics and law professor Dong Fanyu cited Schmitt to support the party’s assertion of authority in the face of ambiguities in the PRC constitution. Whereas constitutional preambles may have little or no legal relevance in interpreting constitutions in liberal democracies, Dong, citing Schmitt, argued that China’s preamble, which characterized the country’s legal system as an outgrowth of national liberation by the party, reflected a pre-legal existential act of founding that gives the document legitimacy. The larger message was that the party, as the fount of law, stood above it.

In the 1990s, scholars such as Wang Lie and Liu Xiaofeng, seeking to counter the idea that Anglo-American-style rule of law and liberal democracy were vital to economic development, were naturally drawn to Schmitt’s writings. Between 1998 and 2002, Liu—an eclectic Swiss-educated self-described “cultural Christian” and defender of Maoism—brought himself into the mainstream of evolving CCP thinking through publication of a number of influential writings on Schmitt and his relevance to contemporary Chinese political economy. Promoting Schmitt’s ideas has since proven a surefire way for scholars to curry favor with the party—providing it with credentialed Western intellectual foundations for defending a political structure and pursuing policies which the West was deriding as a dead end. In consequence, not just writing about Schmitt, but adopting his abstruse, theologically tinged vocabulary and rhetorical style became the height of scholarly chic.

By 2006, most of Schmitt’s important work had been translated and published in Chinese. On the backs of such translations, master’s and doctoral theses on his thought soared between 2006 and 2010. This process represented a new generation of Chinese political and legal scholars weaned on Schmitt. Many of those scholars have since published in English as well as Chinese, reflecting their desire to spread their analysis internationally.

“The emergent ‘Sino-Schmittianism,’ as it has been called, is a body of thought which aims to turn Enlightenment thinking against the West—in particular, the United States—by showing liberalism to be merely a dead-end branch of Western thought pocked by logical flaws and hypocrisy.”

In 2018, Liu published an essay which posited a grand synthesis between Schmitt and Marx, with alleged implications for China’s “world-historic rise.” Referring to the title of Schmitt’s famous early postwar book, Liu argued that Eastern Marxism had brought about a new “Nomos of the Earth”—or spatial ordering of the world—in which the United States would “be squeezed out of Asia,” just as it had squeezed “Old Europe” out of the Western Hemisphere. No longer would the U.S. be able, self-interestedly, to designate the world beyond the Monroe boundaries to be a “free space,” as the European powers had once done with the world beyond Europe. China would close the Asian space, over which geography and history had bequeathed it leadership, to American interference.

The emergent “Sino-Schmittianism,” as it has been called, is a body of thought which aims to turn Enlightenment thinking against the West—in particular, the United States—by showing liberalism to be merely a dead-end branch of Western thought pocked by logical flaws and hypocrisy. It is also openly teleological in a way that Schmitt’s writing was not, presenting itself as a prophetic anti-Fukuyamist argument for the inevitable demise of American universalist ideology.

In sum, the writings of Carl Schmitt play an important legitimizing role for the CCP along many dimensions. Schmitt’s dissociation of “democracy” from liberalism, and his assertion that it requires cultural homogeneity, justifies the party’s characterization of its system as democratic. His insistence that liberal proceduralism, checks and balances, and guarantees of individual rights fuel disunity and threaten national security justifies CCP supremacy and imposition of a Han-majoritarian national identity. His contention that sovereignty resides in the person or body that can declare “exceptions” to the law—where the law is incomplete, or an obstacle to national security—justifies presidential and party rule. His support for a market economy guided by the visible hand of the state serves as an endorsement of its model of state capitalism. His rejection of the notion of “universal law” justifies the CCP’s dismissal of charges of human rights violations in Xinjiang and Tibet.

Internationally, Schmitt’s concept of Grossraum—or “great space” marking out a given region under the stewardship of a great nation—justifies its assertions of preeminence in the Asia Pacific. His related concept of the “pluriverse” of distinct national and regional political communities justifies these assertions in the cause of multipolarity. His insistence that politics is in essence adversarial, and that the identification and neutralization of enemies is a basic responsibility of the sovereign, justifies the party’s preemptive actions to weaken internal and external enemies. And his contention that postwar international bodies operate as disguised tools of American hegemony justifies China’s treatment of the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization as natural arenas for great power competition.

In the global battle for hearts and minds, Sino-Schmittianism enters the field with the millstone of having a Nazi for its standard bearer. But when it comes to predicting the course of political history, at least, Carl Schmitt, unlike Francis Fukuyama, has yet to be proven wrong.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.