I have a pet theory about what’s really wrong with these United States: too many banks. Or, more precisely, too many bankers at too many institutions that aren’t banks but act like banks, abandoning their core missions to concentrate on banking or banking-adjacent activities.

American Airlines stinks on ice in part because it isn’t really an airline at all—it is a credit-card company that owns some airplanes. While those planes may fail to take off or land on time 19 times out of 20, you can be sure that 27 times out of 20 the flight crew will turn up the volume on the loudspeakers and try to sell passengers some credit cards. The U.S. government at its worst is indistinguishable from a bank, trying to pilot society by remote control through subsidized credit for everything from college tuition to so-called green energy.

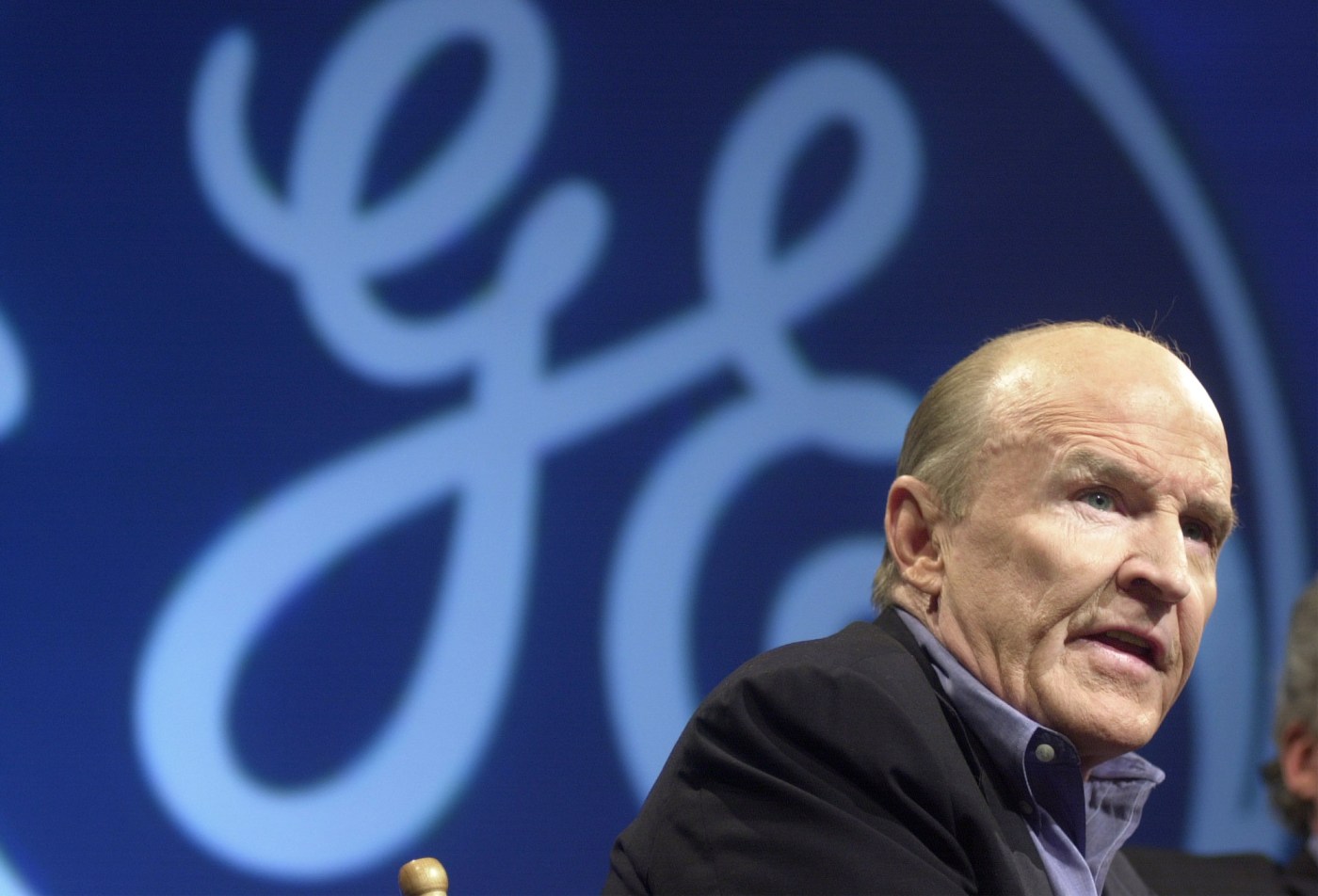

And then there is the sorry story of General Electric, as told by noted business journalist William D. Cohan in Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon. (Cohan’s publishers must have real faith in the book: You’ll notice that the company’s name does not appear in the book title, and its logo appears on the cover only as 18-point shadow text.)

GE—the company that once boasted, “We bring good things to life”—helped bring to market world-changing products from the electric lightbulb to the jet engine. Yet it ended up being a company that mostly played with money through GE Money Bank, a subsidiary of GE Capital. And it did so with a genuinely spectacular level of incompetence.

GE Capital was involved in everything from private-label credit-card programs to automobile financing to—of course!—subprime mortgages, and GE Capital detonated a big enough bomb on the firm’s finances during the financial crisis that it nearly took down the entire company, which limped on until 2021, when its leaders that it was better to have three incompetently managed companies rather than one big one. That’s an ironic reversal for a former Frankenstein’s monster of a corporation that had typified the mania for acquisitions-driven growth under the leadership of Jack Welch.

When GE was finally taken off the Dow Jones Industrial Average, it was the last of the original lineup. But its shares constituted less than one-half of 1 percent of the index’s value. Some bank it turned out to be.

There are a handful of famous names indelibly linked to General Electric, and Cohan doesn’t leave any of them out. One is that of the aforementioned Jack Welch, who also is the subject of a new unsympathetic biography, one by David Gelles of the New York Times bearing the logorrheic title: The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America—and How to Undo His Legacy. (Gelles, New York City-born and Bay Area-raised, is also the author of a book about “mindfulness” meditation and its role in business; God save us from these coastal journalism-school graduates and their lamentations for “the heartland.”)

The biggest name associated with GE is that of Thomas Alva Edison, who seems to be diminished a little bit more every time his name appears in print. Cohan argues persuasively that the famous inventor had a minor role in the company, as he already was pretty well checked out and ready to move on to other things by the time the entity that became General Electric was really up and running. Edison still provides a useful anchor for Cohan’s exploration of the first phase of General Electric’s history.

The company was founded in 1892, when the success of a firm or an entrepreneur was measured not only in dollars earned but in patents granted. In fact, as Cohan tells the story, the chapters of GE’s story are those of Big Business more generally: from the Age of Inventors into what we might call the Age of Cartels. This was typified by GE’s implication in any number of price-fixing schemes and backroom collusion at the dawn of what President Eisenhower would call the “military-industrial complex,” of which GE was, for a generation, the corporate personification. From thence GE led the way toward globalization and financialization, and then into decline and incoherence, as the torch of innovation was passed to a new generation of firms and entrepreneurs of a kind mostly alien to the thing that Jack Welch and Jeffrey Immelt built.

And it’s “Jack” and “Jeff,” by the way—this is a book written on a first-name basis, for whatever reason. At least in part: Marconi, Edison, and Morgan are “Marconi,” “Edison,” and “Morgan”—we might read the transition from surnames to given names as marking the transition from Cohan’s history to his journalism. The journalism is no doubt more complete and better informed, but I found the history more interesting.

“GE is a company that matters in the world,” declared CEO John Flannery. “For a hundred and twenty-five years, we just tackled the biggest challenges the world faces. So light, flight, health—these are the absolute underpinnings of the modern world. It’s always been this mix of sparks of innovation with just sheer determination to succeed. It’s been a company that does things, solves things, lines things out, sweats the details. The harder, the better; bring it on.” So it may have seemed, for a long time—but by the time of the 2007-08 financial crisis, GE was a bank—or it was a half a bank, earning just under 50 percent of its profits from the bank it owned.

It also made many of its billions as a government contractor, a role in which it was occasionally guilty of quite significant fraud. The early 1990s saw the firm paying out one of the largest combinations of civil and criminal penalties for fraud in the history of federal contracting. The guys in white lab coats inventing cool new things in the basement were only a relatively small part of the story—so many little Edisons beavering away while the Jack Welches of the world slipped around in money like gladiators in blood. But the swashbuckling stuff is more exciting: As Cohan tells the story, Welch’s first big challenge at GE was figuring out how to make plastic coatings stick to copper wire—an interesting engineering challenge, no doubt, but not the sort of story that leaps off the page.

If GE did matter, why did it matter? One way of understanding GE is considering its role as a vessel for ideology. When the ideology of elite Washington was corporatism, GE was corporatist. When the ideology was Cold War liberal-internationalist, GE was Cold War liberal-internationalist. When the millennial ideology emphasized finance as a kind of magic machine for making money out of money, GE was a bank, or a half-bank.

I do not fault Cohan for failing to have written a political book, but the political moments of GE’s history and the ways in which the firm served as a vehicle for distinct national ideologies at various points in its history seems to me more relevant to the story than are some of the elements Cohan chooses to emphasize, for example in his repetitious and slightly Freudian account of Welch’s semi-Oedipal relationship with his mother.

On that score, some language criticism, too: Cohan describes Welch as being “orphaned” after the death of his parents 15 months apart, but a married father in his 30s well into a successful business career is hardly an “orphan.” Welch says he cried for four or five days straight after the death of his mother, and Cohan somehow does not ask: “What was wrong with you?” Elsewhere, Cohan describes a particular business challenge as being “like trying to crack a safe with plutonium inside—one wrong click and the whole thing blows.” That isn’t how plutonium, or safes, work.

Readers will gain much from Cohan’s account of GM’s price-fixing shenanigans in the 1950s and 1960s, when the company led an off-the-books cartel to divide up the power-equipment business and prevent price competition after a round of steep discounts had left all the competitors in the industry struggling. But these cartels did not come out of nowhere: It was a commonplace of Progressive Era and New Deal thinking that government and business should work together to prevent “destructive competition,” and much of the business regulation of the late 19th and early 20th century was directed not at breaking up monopolies and cartels but at creating them (as with the Bell system) or causing industry groups to behave as proxy monopolies and proxy cartels (as in the old milk-pricing scheme). GE came to its position of greatest prominence in the postwar era, when government planning was at the apex of its credibility and when it was fancifully assumed that government could be organized around scientific findings and principles.

That big firms were expected to play a semiofficial role in national life was even expressed in their names: General Electric, General Mills, General Dynamics, the U.S. Steel company. Cohan is not entirely uninterested in the question of how GE fit into the ideological life of the country, but he doesn’t really dig deep. When people say, as they do, “We need to run the government like a business,” GE is the business they once meant.

But perhaps that line of inquiry seems too grandiose for Cohan, who seems more at home chronicling Jack Welch’s Mad Men antics, leaving the wife and kids at home to pick up young women in bars and then brawling in the parking lot with the men who turn out to be the husbands of his objects of desire. He is surely comfortable—far too comfortable—with business cant: Almost every business figure considered in this book seems to speak and think exclusively in businessmen’s clichés. The quoted language is in the main remarkably tedious.

One problem with books of this kind is that the authors sometimes feel the need to put in every single detail they know—every minor character and every minor character’s résumé. And Cohan knows a great many details: He worked with some of the characters in the book when he was a finance monkey at Lazard, and he does not suffer from excessive economy in narrative.

At one point in his career, Jeffrey Immelt decided to climb Mount Kilimanjaro with his daughter. Cool—a sentence? Two sentences? No, the reader will endure eight pages: Jeff feels like he has been a neglectful father, Jeff’s daughter is an assistant to Lorne Michaels and less of an entitled brat than Jimmy Buffett’s niece, Jeff plays golf but doesn’t work out very much, Jeff starts walking to the bagel shop but doesn’t give up bagels, Jeff cajoles his security guy into going along on the trip, the security guy shares his considerable back story, Will Ferrell makes fun of Immelt’s mountain-climbing ambitions, the security guy fights with his wife over a cruise they had planned for the same week, the security guy marvels at the fascination of his own life and the fact that he is on a mountain with the chairman of GE, they fly a small air wing to Tanzania, they climb, the security guy gets dehydrated and doesn’t take a wee for almost two days, they get to the top, they go back down, people stumble, people learn the Swahili word for “slowly,” people talk about how their legs hurt—seriously, that’s how this goes—Jeff calls his wife at the end and says he’s okay, Jeff calls to check in with the office. And we end up with: “Would the persistence he supposedly learned climbing Kilimanjaro help him cure what ailed GE?” That’s a lot of work to get to a vague question about the character development of a man who was, at the time of these events, old enough to collect Social Security.

There is a sense of padding in this book—which is a very long book not in any obvious need of additional stuffing. This is history as understood by Arnold Toynbee: “just one damned fact after another.” Does it add up to something other than a kind of very comprehensive corporate audit?

Toward the end of the story, GE CEO John Flannery says of the firm’s institutional investors: “They understand the importance of GE in the world.” I suspect William D. Cohan does. I am not entirely sure his readers will.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.