When we were youngsters in the ’80s, a buddy of mine had one of those cars with a digital dashboard that seemed high-tech at the time. “Watch me hit the turbocharger,” he would say, and the speedometer would show us jumping instantly from 60 to 95. Of course, the little four-banger in that Reagan-era econobox wasn’t suddenly burning rubber around Loop 289 in Lubbock, Texas—he was just toggling between miles per hour and kilometers per hour. It was his favorite little joke: We all had crappy cars back then, as teenagers did.

Changing the units of measure does not change the reality of the phenomenon being measured. If your employer starts paying you in Japanese yen tomorrow instead of U.S. dollars, the number on the paycheck will be about 146 times what it would have been otherwise. But you aren’t better off—you’re just measuring your income by a different metric. (You’d probably be worse off, in fact: Changing those yen into dollars you can use will entail paying a fee, because transaction costs are a thing.) The thing about inches and centimeters and miles and kilometers is that you can switch from one to the other, but an inch is always 2.54 centimeters—the exchange rate is fixed. An inch is an inch is an inch.

But it’s different in economics, where a dollar is not always a dollar and is not always 146 yen.

You can measure your income in all sorts of ways and get different-looking outcomes. If you got a 10 percent raise last year, then your income is 10 percent higher as measured by U.S. dollars. But it’s a lot lower if you’re measuring in gold, which has gone up in price by about 30 percent in the past 12 months. Your income may be 10 percent higher in dollar terms, but it is lower in gold terms, in egg terms, in house terms, etc., and it is more than 10 percent higher if measured against shares of Astera Labs stock or a gallon of diesel.

The number on your paycheck, in an economic vacuum, doesn’t mean anything at all. Wages are meaningful only in relation to prices—it is not the number on the check that matters but what you can get with it. If a beachfront property in Malibu cost $50 and a Rolls Royce cost $10, then the guy who makes $14,000 a year is fabulously rich. But a “six-figure income” is less something to boast about when the median house sold costs more than $400,000. A seven- or eight- or nine-figure income was basically nothing in Germany in the 1920s, when the price of a loaf of bread hit 200 billion Reichsmarks.

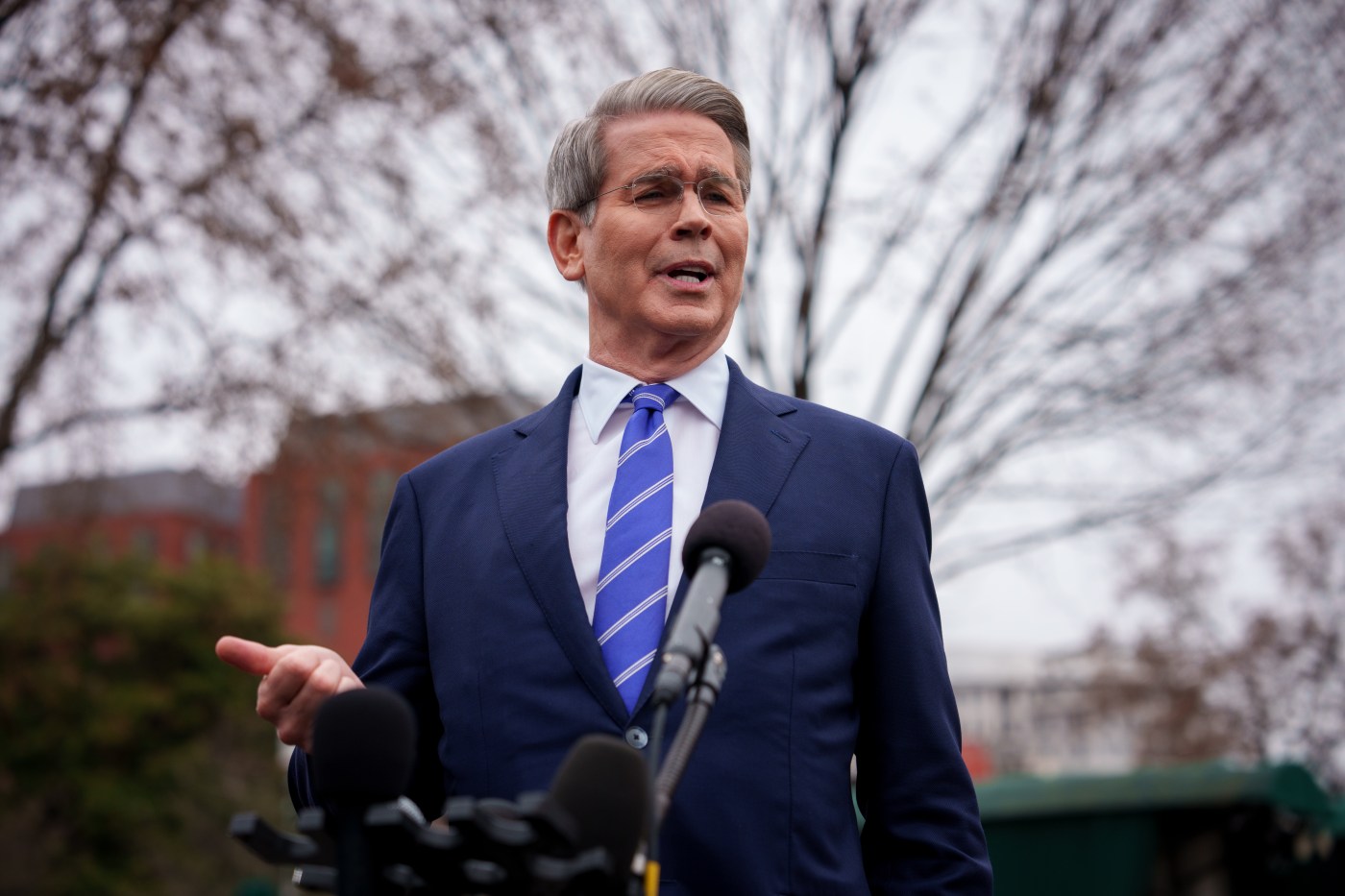

You’d think that this would not need explaining to a man such as Scott Bessent, the hedge-fund guy who currently serves as Donald Trump’s treasury secretary—because, of course, Mr. “Real America” hires his help from Soros Fund Management. But during a speech to the Economic Club of New York—whose members somehow did not laugh themselves into aneurysms—Bessent declared: “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American dream. ... The American Dream is rooted in the concept that any citizen can achieve prosperity, upward mobility, and economic security.”

“Upward mobility” is another way of saying “higher real wages,” “real” in this context meaning “inflation-adjusted,” i.e., higher wages relative to overall prices. “Cheap goods” is another way of saying “goods with relatively low real prices,” meaning goods with low prices relative to wages. It surely was not lost on the members of the Economic Club of New York, sniggering discreetly into their pinstriped lapels, that lower real prices and higher real wages are, in the technical terminology of academic economics, the same goddamned thing. I don’t mean that one is as good as the other or that one is a useful substitute for the other—they are the same thing in the same way that 3+2 is the same thing as 2+3.

Higher wages that aren’t higher relative to prices aren’t higher wages; lower prices that aren’t lower relative to wages aren’t lower prices. Each is measured in terms of the other.

I have not elected myself tribune of the plebs, but I think it is safe to say that lower-income Americans could stand to hear a good deal less from billionaire and near-billionaire hedge-fund dorks about how consumer prices aren’t high enough, that those “cheap goods”—products with low prices relative to Americans’ wages—are part of the problem. It takes a special kind of Ivy League-educated asshat—and there are a lot of them wandering around these fruited plains—to believe that Americans are being somehow victimized by the fact that the stores are full of things they want at prices they can afford.

In real terms, a decent pair of shoes costs an American worker a lot less than it did 50 years ago, and the trend broadly holds true for all sorts of goods ranging from technology (that Gordon Gekko brick of a mobile phone in Wall Street cost about $13,000 in today’s dollars and you couldn’t even use it to Snapchat your coke dealer) to cars, which not only were more expensive back in the ’70s and ’80s but also were absolute junk compared to a 2025 Honda Civic or a Kia Soul.

But it doesn’t hold true for a few things that Americans really care about: education, health care, and houses, among other goods. One of the things those products have in common is that they are not much traded internationally, though some of their components are. Which is to say, the things that have performed the worst in meaningful terms are the ones most protected from the pressures of globalization.

Education and health care are delivered to a considerable degree outside of competitive, market-driven transactions, and, like construction, their delivery is geographically constrained. Policy choices–from land-use regulation to various kinds of price controls–inhibit innovation, investment, and abundance in these markets. Location-dependent jobs have tended to be associated with better real wages for decades for obvious reasons—and, while those jobs are not easily offshorable, it is no accident that industries such as health care and construction have relatively large numbers of immigrant workers. Sometimes, work goes where the workers are, other times, it is the other way around. You can try to impose your politics on the marketplace, but the underlying market forces will work to reassert themselves wherever they can.

What Scott Bessent et al. do not seem to appreciate is that, in economic terms, the “American dream” they’re talking about would have been much better served if college tuition, health care, and housing had followed a price-quality-innovation path more like that of the iPhone and less like that of the U.S. Postal Service. That means more competition, not more protection. What Bessent et al. propose is to apply the same kind of suffocating protection to the U.S. economy as a whole that we have in the public sector and in dysfunctional markets such as housing, making our high-tech economy as innovative, affordable, and high-performing as the Philadelphia public schools or the St. Louis Police Department or the housing market in Palo Alto.

Is a more affordable mortgage or insurance premium “the American dream” in full? Of course not.

But, then again, neither is being bossed around by a semi-literate, porn-star-diddling game-show host and his dopey hedge-fund henchmen, who all seem to think what Americans really need is higher prices at Walmart.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.