Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

One of the worst aspects of the social media era is the convenience of impulsivity. It’s not merely that it is easier to say unwise things publicly—although it is—but that it is easier to say anything publicly. Impulsive posts are a poor representation of people not just for what they choose to say but also for what they choose not to. While many posts about events merely reflect how emotionally charged a person was in a given moment—subject to the unceasingly capricious vicissitudes of life—their social media presence is viewed as a full and exhaustive accounting of the rigorous application of their principles. This gap between arbitrary emotional whims and a perceived logical coherence paints a deeply distorted picture of ourselves.

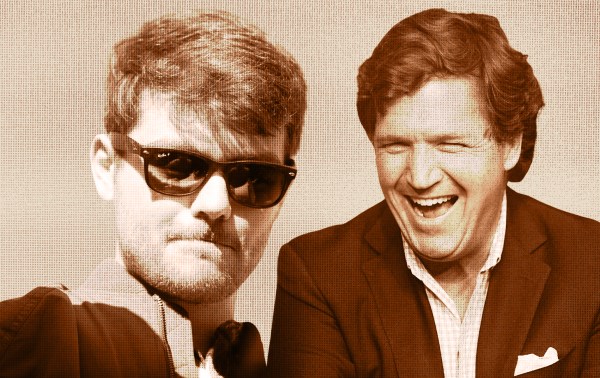

The criticism runs, “If you cared enough about X to post about it, and you did not post about Y then you must not care about Y. And we all can agree Y is worse than X.” Some of those who care deeply about suffering in Gaza are forced to explain why they have not shown similar outrage over other ongoing atrocities, for example those in Sudan or Burma. Similarly, those who were moved by the assassination of Charlie Kirk are forced to answer for silence or insufficient outrage in response to other assassinations or attempts, other instances of gun violence, police brutality, or the aforementioned devastation in the Gaza Strip.

This desire to hold up insufficient outrage as proof of hypocrisy or selective commitment to principles misunderstands the human condition. Adam Smith, in his work The Theory of Moral Sentiments, draws an interesting comparison: He juxtaposes our dour yet composed reaction to the news of an earthquake devastating the population of China with the calamitous reaction we would have to the news that we would lose our “little finger” tomorrow:

If he was to lose his little finger to-morrow, he would not sleep to-night; but, provided he never saw them, he will snore with the most profound security over the ruin of a hundred millions of his brethren, and the destruction of that immense multitude seems plainly an object less interesting to him, than this paltry misfortune of his own.

Smith asks, given the facts of this natural reaction, would we trade the lives of those millions to save the finger? The obvious nature of the answer makes Smith’s point. The fact that our emotions drive us in one direction and our virtue drives us in the other reveals the nobility of human nature. We cannot change our emotions; we can merely choose how to respond to them.

When considering the death of Charlie Kirk, it is not confounding that Americans would be moved by the assassination of a political pundit on their own soil. Such a murder is often more jarring than other tragedies because of what it says about the state of our society. It signals a fragility in our culture of freedom of speech and a lack of safety in holding strong opinions. It tells Americans that one need not be a high-ranking government official to be the target of political violence. All Americans have opinions—one could argue this is important to being American—and an act that makes them feel unsafe doing something as mundane as sharing those opinions is bound to affect them on an emotional level.

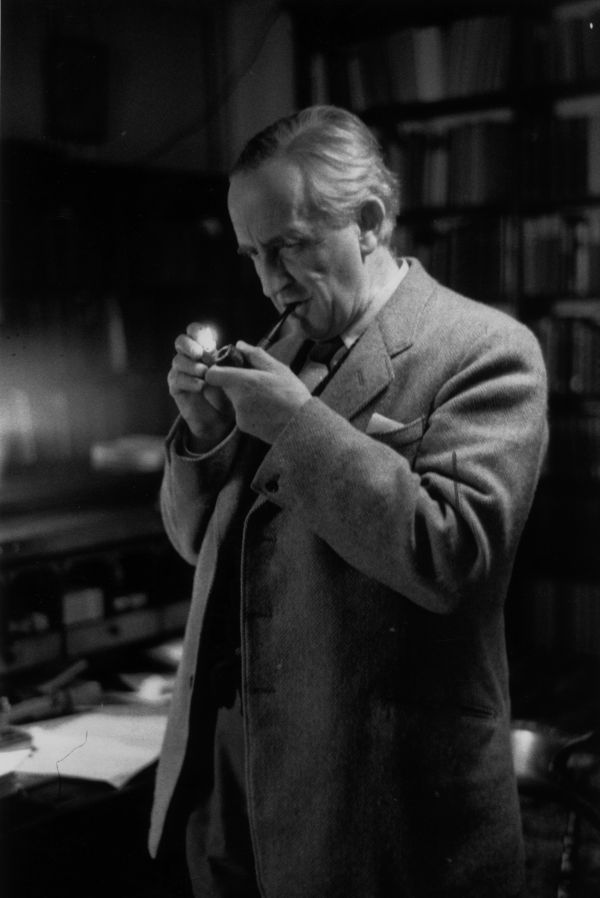

To me, a person who strongly disagreed with Kirk and who believed his work spoke to the worst tendencies of our culture, the assassination is a tragedy. And those on the right with whom his message resonated have even more reason to feel discomfort. Someone they admired, whether that admiration was well-placed or not, lost his life for the content of his speech.

People are moved in confounding ways. We need not look further than the unpredictable selection of movies that bring us to tears to understand this. Why do I choke up at Raksha’s speech to Mowgli when he is forced to leave the pack, but remain unmoved as I casually read through the tally of devastating events taking place across the world every morning? I have not the slightest clue.

Social media has become a reflection not of the precise application of reasoned principles, but of the erratic directions in which our emotions pull us. And so, it is a terrible medium through which to judge who people actually are. Whatever the event is that ignites people’s passions, it is a manifestation of what feels like their little finger. It is not the hierarchy of how they view the tragedies of the world, but what affected them in that moment. Their silence on a given issue or in response to a given event does not indicate tacit approval of it, but rather ignorance about its existence, a lack of emotional salience, or that they merely had something better to do than pontificate when they came across a post about it. Choosing to speak about one thing does not mean a person cares only about that one thing.

Humanity does not contain the capacity to universally commiserate with all the world’s suffering. Such a burden would crush anyone attempting to bear it. As opposed to keeping a running tally of tragedies to gauge whether someone’s outrage is properly proportional, why not have compassion for a human response to a tragic event that, for reasons that are both intractable and irrelevant, hit home with them?

The death of Charlie Kirk is a tragedy, full stop. The deaths of civilians in Gaza is a tragedy, full stop. The slaughter on October 7 was a tragedy, full stop. The assassination of a Minnesota lawmaker and her husband this summer was a tragedy, full stop. Any death of a young black man at the hands of law enforcement is a tragedy, full stop. Tragedy either is or isn’t: It is a waste of time to compare the devastation of one tragedy to another. And so there is only one reasonable response to people moved by a particular event: compassion. They are not saying that they would trade millions of strangers across the world for their little finger, but simply that they are strained by its loss. As anyone would be.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.