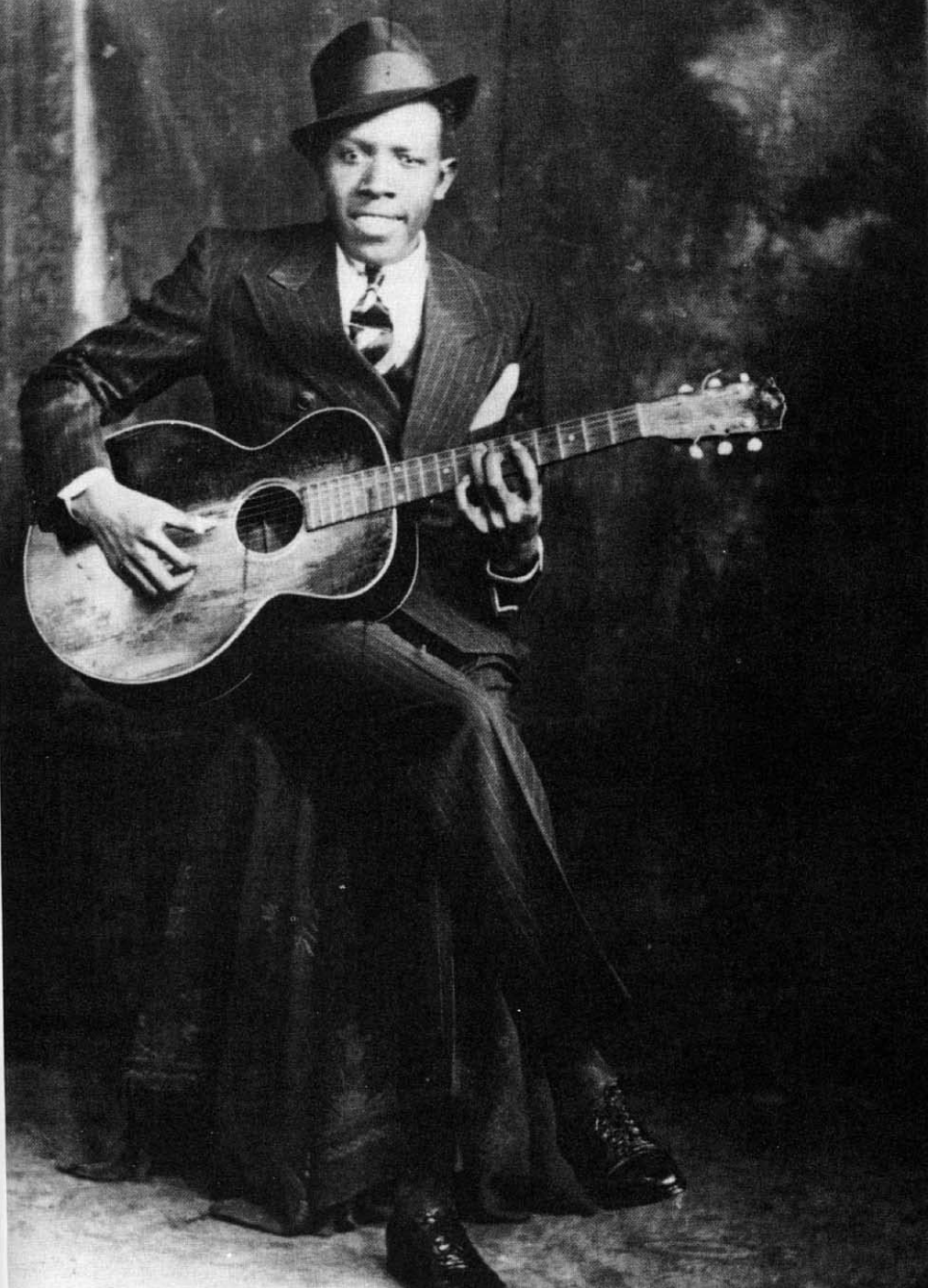

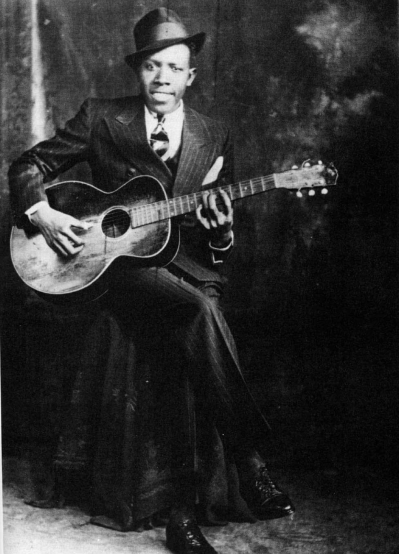

The story of Robert Johnson, one of the most influential blues musicians to have ever lived, is an enigma. His quick transition from novice guitar player to master of the craft is attributed to a deal with the devil. His cause of death at 27 remains murky and the site of his grave is uncertain. Even information about what Johnson looked like is slim—there are only three published photographs of him, the most recent revealed two years ago by a relative. The mystery does more than just add layers to Johnson’s story: It highlights the miracle that we even know of Johnson’s genius.

Johnson, born in Mississippi in May of 1911, was the youngest of 11 children born to Julia Major Dodds, the daughter of freed slaves. His conception was a result of Dodds’ affair with a field hand named Noah Johnson after Dodds’ husband fled Mississippi and his family to avoid being lynched over a dispute with white landowners.

The South that Johnson knew was two generations removed from slavery and the failure of Reconstruction—the era of Jim Crow was taking hold. Legalized segregation and lynchings led many black Americans to migrate north to safer conditions and more opportunities. But Johnson did not leave. Johnson stayed in Mississippi and picked up a guitar.

According to blues patriarch Son House, Johnson’s career did not begin well. His first performance in front of a live audience resulted in him being removed from the stage. Johnson responded by disappearing for around a year before returning to the juke joint where he had previously been ejected. After receiving permission to take the stage, Johnson shocked the bar patrons with the playing of someone who had, in a very short time, not only become a master of his craft but an innovator—a rapid transformation that led to the myth that Johnson had sold his soul to the Devil.

Johnson took his act on the road traveling and playing wherever he was given a chance—and in 1936, a talent scout for English-American music producer Don Law offered him some time in a recording studio. Johnson’s first recording session in November 1936 produced “Terraplane Blues,” a modest success that led to a second recording session in June 1937. Johnson recorded a total of 29 songs, including “Sweet Home Chicago,” “Cross Road Blues,” and “Love in Vain,” earning approximately $700 with no royalties in an era in which average annual income was approximately $1,150. While Johnson’s $700 was a nice reward for about a week’s work, it did not make him rich.

Fourteen months after Johnson’s final recording session, he died of unknown causes. His burial was undocumented, no autopsy was conducted, and his death certificate was not discovered for thirty years. His acquaintances only learned of his death by word of mouth. Rumors spread that Johnson had been poisoned. The plantation owner where he died believed the cause was syphilis. The world will never know the truth. Johnson’s final resting place is unknown, with three cemeteries claiming they have his true grave.

While living, Johnson did have his supporters. American Record Corporation, the label in possession of his recordings, continued to release singles of his music until 1939, when it was purchased by Columbia Records. John Hammond, a music producer, wrote about Johnson’s talent and attempted to track him down for a live music event at Carnegie Hall in December 1938 not realizing that Johnson was already dead. The concert would have put Johnson on stage with notable artists, including William James “Count” Basie and Benny Goodman. An event of that magnitude would have exposed Johnson’s talent to a larger audience. Instead, aside from some blues histories which mentioned Johnson in passing, his music went largely unnoticed for decades.

Columbia Records’ 1961 release of “The King of Delta Blues Singers,” a compilation of Johnson’s work, finally cemented his place in history, allowing a new audience of young, mostly white musicians to discover his genius. Since the album’s release, Johnson has influenced many legendary artists. Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and Cream have covered songs from Johnson’s small catalog. Eric Clapton, a founding member of Cream, recorded a full album of Johnson’s material. Clapton, in an interview with NPR in 2004, described being overwhelmed when he first heard Johnson’s music because it was “more powerful than anything else I had heard or was listening to.”

There have been many individuals in modern America who have achieved success despite incredible odds; few can claim to have more stacked against them than Johnson. Poverty, prejudice, and an early death robbed Johnson of the success he so richly deserved. We are lucky that the passage of time has changed that, and Johnson’s music is now easily accessible and celebrated. The forgotten man is now a legend.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.