We’ve entered the Twin Peaks phase of public opinion research for the 2024 election: widely open to various interpretations and, at the end, more annoying than charming.

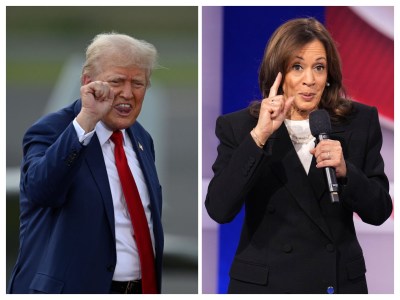

In an average of high-quality national polls, Vice President Kamala Harris leads former President Donald Trump by 0.2 of a point. A blip. Basically nothing.

Polls haven’t been this tight at the end of a presidential race since 2012, when incumbent President Barack Obama had a similarly gossamer-thin advantage over challenger Mitt Romney. But, while the polls were tight, the race was not. Obama won by nearly 4 points nationally and cruised to an 332-206 Electoral College win when he overperformed the polls substantially and Romney barely missed his expected number.

In 2016, the race didn’t look nearly so close as it had four years before, but that wasn’t right either. The nominees of both parties outperformed their polls, but Trump beat his number by a point or so more than Hillary Clinton, enough to nick her in the Democrats’ must-win states of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Four years later, the race looked like a blowout, but was actually pretty close. President Joe Biden could have won without the two traditionally red states he flipped, Georgia and Arizona, but those were very close, and in the weakest of Biden’s must-wins, Wisconsin, Trump came within 0.6 of a point.

It’s been 16 years since a presidential race a week out from Election Day looked like what it ended up being.

So, is this a race that looks close but isn’t, or are we heading for a deadlock like we haven’t seen since the start of this century?

I could tell you what appears to me to be more likely to happen, but that’s all it would be: a hunch based on appearances. And you probably have your own hunches.

Republicans, as is their traditional mode, are wildly overconfident about their chances for victory, a tendency intensified by the stunning upset of 2016. Democrats, as much traumatized by 2016 as Republicans are buoyed by it, are also reverting to their traditional preelection posture: panic and despair.

Unlikely as I am to change someone’s mind about something unknowable and, for one more week, unprovable, here are the best arguments for why Trump and Harris each will win, starting with the party out of power:

Why Trump Is Sure to Win

The swing state shift: If there’s been one motif running through my coverage of this campaign, it’s the swing state shift: the 1.7-point Republican lean of the seven swing states—Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin—compared to the nation as a whole. If Clinton could get nicked in the Upper Midwest while winning by more than 2 points nationally, Harris looks like dead meat if the polls are right.

If the states stay in roughly the same order as they have in the previous two cycles, that would be something like 292 electoral votes for Trump. A little extra boost in the polls, and he’s at 313.

Bad vibes: The sitting president has an approval rating of, basically, soggy french fries. Many people will still accept him as better than nothing, but 58 percent would rather pass. His vice president is running for a four-year term, and while the same poll finds her with a substantially higher favorability rating than her boss, by about 10 points, she is still very much tied to an unpopular status quo.

And while Harris has substantially closed the gap with Trump on the question of which candidate would be better for the economy, overall views of the current economy remain decidedly poor. Harris is slightly less personally unpopular than Trump—who remains basically stuck underwater—but still represents change. If Republicans had a pure change candidate instead of one that was a change back candidate, this advantage would probably be much more pronounced. Even so, as Hillary Clinton learned in 2016, in periods of voter dissatisfaction, it’s better to be the out party than the in party.

Error message: Republican’s confidence is very much rooted in Trump’s back-to-back overperformances compared to national polls. So this one is pretty simple: The polls always underestimate Trump, therefore, if Trump is already at nearly 48 percent nationally, even a modest amount of polling error against him would put Trump in a national popular vote victory and a relatively easy Electoral College win.

We can say that there’s no clear partisan correlation over time to historical polling error, but if Trump is two-for-two on final result versus polling performance, the obvious bet is that he will do it again. And since he’s so much higher in the polls now than he was at this point four or eight years ago, Trump needs very little to get where he needs to be.

If you believe Trump is sure to win, you likely think that pollsters have not been able to fix the problems of low response rates among Republican-leaning voters. If that’s so, Trump may be headed for the biggest Republican victory in at least 20 years.

Cultural lag: During the brutal battles over gay marriage at the beginning of the century, progressives were frequently confounded by the fact that the non-white voters who were typically part of their coalition did not join them in the drive for marriage equality. Fiscally liberal and dovish on foreign policy, many black and Hispanic voters still jumped offsides when it came to cultural issues.

So when we see Donald Trump doing better with black men, a key constituency for Democrats, one wonders if Harris’ gender might be part of the story. Even if white America is ready for a female president, could it be that minority voters are not? Republicans’ closing argument on transgenderism and other wedge issues seems aimed directly at these men.

You don’t need the long-debunked Bradley effect to believe that Harris is being hurt by a combination of her own gender and past culture war stances. Even if the polls are right on the money, we’ll be able to show how culture and gender made this race harder for her.

Why Harris Is Sure to Win

Normalized Trump: One of the most striking things about this election compared to the previous two is how little the polls have moved over the closing two months. The race has closed since mid-September as Harris ticked down 0.4 of a point and Trump climbed 1.6 points, but that was nothing compared to the wild swings of 2016 and 2020.

The reason for that seems to be that voters made up their minds far earlier this time than they did before. And that seems mostly to be a story about Trump, not Harris.

We’ve been wrestling with the same question for weeks: Is Trump running better or is he just polling better? Are Republicans more comfortable with Trump now—and more fearful of the alternative—than they were before and were ready in advance to back him?

In the past, 2016 most notably, there was a great deal of hemming and hawing among GOPers about whether they could support Trump, but in the end, almost all of them did. As we observed in the Republican primaries, though, this is a much more unified party than at the start of the Trump era. Polling error explains some of Trump’s past overperformances, but not all of it. The rest can best be attributed to Republicans coming home to roost, Republicans who were always likely to stick with their party.

If that’s the case, then it may be that Trump, the most famous political figure in the world, doesn’t have much more room to grow. And if he really is polling better rather than actually running better, Trump will end up, yet again, with about 47 percent of the national popular vote and, most likely, a loss.

Turnout is what?: One of the reasons that 2020 was so much closer than expected was the massive, record-setting turnout. Pandemic voting changes and Americans with more free time and a great deal of anxiety poured themselves into the election in a way we haven’t seen in the modern era.

While it seems reasonable that turnout won’t fall back to 2016’s rock-bottom levels, it seems equally unlikely that we will see 2020-level turnout again.

Once, as recently as 2016, lower turnout tended to be good news for Republicans, but as a series of midterm and special election victories have shown since then, Democrats seem to be the more reliable voters.

That’s certainly going to be less true for Republicans with Trump on the ballot, helping to propel the party’s new working-class coalition to the polls. But as Democrats’ coalition comes increasingly to resemble the old GOP model and its heavy reliance on suburbanites and high-propensity, college educated voters, lower-turnout races can work in their favor.

Page turner: As much as we can say that the forces of “change versus more of the same” work in Trump’s favor, there is no question that it’s not as clean of a question as it was in 2016.

Back then, Trump was very much the candidate of change. But, as we discussed above, this time, he is the candidate of change back. And while Harris’ ill-defined place in the American consciousness does make her an easier target for attacks on her character and fitness, she does retain some of the blank-slate quality that Trump and Obama enjoyed in their maiden voyages.

Republicans complain about her evasions and non-answers to even simple questions, but the intent is clear: to hold space for voters turned off by Trump to project their best version of her in their own minds. Indeed, the tension between her and Biden feeds into this larger narrative.

In open seat elections in 2016, 2008, and 2000, the winning candidate was the one who made the most convincing argument that circumstances would be different if they won. It’s a tougher play for a sitting vice president, but she’s going for it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.