We’ve spent a lot of time here at Capitolism documenting the many problems with U.S. industrial policy at the federal level—a lot. Among those problems is the risk that subsidies in one nation prod other nations to follow suit, thus setting off a “global subsidy race” that ultimately makes almost everyone worse off (especially once the tariffs get going). There is, however, another subsidy race that’s been going on for decades and, despite high costs and minimal benefits, seems to be getting worse—thanks in large part to new U.S. industrial policy.

This race, however, is happening among American states and localities, not different nations, and it’s the subject of my brand new paper (with Cato Institute colleagues Marc Joffe and Krit Chanwong). In it, we document the growth of state and local corporate subsidies—euphemistically called “economic development incentives” (because who could oppose that?!)—and show how oft-promised benefits usually fail to materialize, while oft-realized problems are significant yet usually ignored. We also explain why, despite all the evidence against these corporate incentives, politicians and many voters still love ’em. Fortunately, we offer some solutions—used here and internationally—that might end the race once and for all.

Documenting the Subsidy Race

If you’re reading this from the United States, you’re probably aware of economic development incentives in some form or another, and you might even be aware of how states and localities—regularly prodded by rent-seeking corporations—use incentives to compete for new investments in their jurisdictions. Perhaps most famous in this regard was Amazon’s HQ2 project, in which the company openly—and quite brazenly—solicited bids for subsidy packages from American cities eager to host the facility. And if you’ve ever seen a local politician bragging online about some new corporate office in your hometown, there’s a good chance a business incentive was attached.

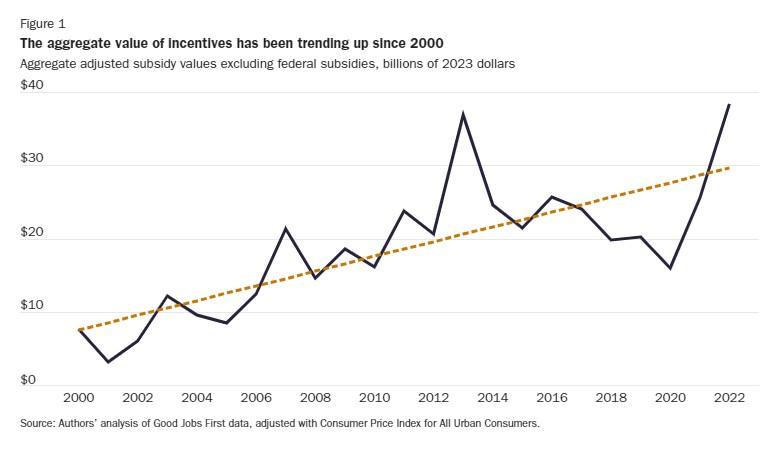

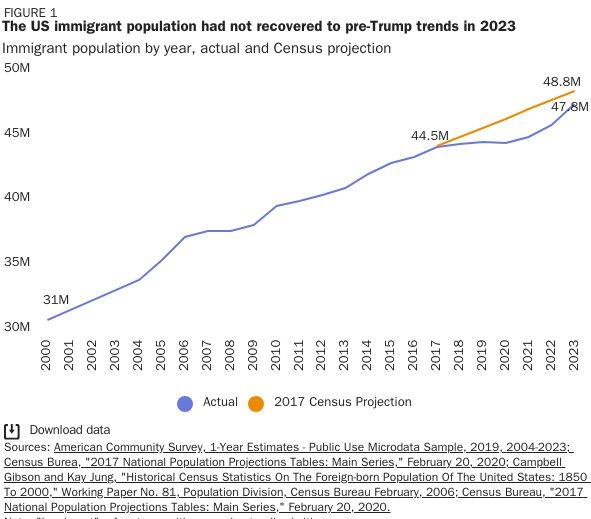

As we document in the paper, however, the “economic development” game is a lot more than just a few isolated anecdotes, with one popular measure showing nonfederal business incentives hitting almost $40 billion in 2022, up from just $7.5 billion two decades ago (adjusted for inflation):

The recent spike in these subsidies is sure to continue in 2023 and beyond because much of it is, as we show, tied to U.S. industrial policy initiatives, particularly for electric vehicles and semiconductors, that were just getting going and have since offered trillions in potential subsidies for domestic manufacturers. Indeed, government officials at various levels (President Biden, members of Congress, governors, mayors, etc.) have repeatedly held joint public events or issued press releases touting each other’s support for the subsidized projects at issue. (The office of North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper even went so far as to directly contact the Biden administration—at Vietnamese EV maker VinFast’s request, naturally—about possible federal support.) Scratch almost any project linked to U.S. industrial policy, and you’ll probably find state and local subsidies underneath.

Our subsidy totals undoubtedly undersell just how much corporate welfare states and localities dole out each year. That’s because incentives suffer from a serious lack of transparency and because many are hard to quantify. On the former, for example, most states have limited disclosure requirements, and negotiations are often conducted in secret, away from the prying eyes of wonks like me. On the latter, subsidies take the form of not just things with clear budgetary costs (tax breaks, cash grants, cheap loans, etc.) but lots of other things that don’t easily show up in a budget line item (if at all)—“free” (taxpayer-funded) land, job training, infrastructure, or utilities; expedited regulatory approvals; and so on. Throw those things in too, and you can get subsidy totals of well more than $100 billion per year.

High Costs and Wildly Oversold Benefits

And this is just the budgetary cost. As we document, state and local business subsidies also raise numerous other—often invisible—costs, such as:

- Opportunity costs. Budgets are finite and especially limited at the state and local level because these governments can’t just print money or run big deficits. Thus, spending on corporate incentives necessarily means either less revenue available for policies benefiting the general public (e.g., tax cuts or infrastructure spending) or higher taxes to pay for the subsidies, which will likely mean lower economic growth.

- Competitor costs. Subsidies disadvantage local businesses that compete with subsidized, often out-of-state firms for customers and resources. Local incumbents might also face higher costs as their government-backed competitors acquire scarce local labor, materials, and other resources. And, because incentives are disproportionately awarded to larger, more profitable firms, these unseen effects may be especially damaging for newer or smaller companies.

- Deadweight costs. Subsidies cause companies to redirect resources from efficient and socially productive activities toward promoting less productive ventures (like this struggling New Jersey megamall) or seeking economic rents arising from place-based subsidies. Incentives also draw corporate money away from productive business operations and instead into the political system or toward expensive “site selection consultants” that negotiate subsidy packages and pit localities against each other. Money devoted to these rent seeking activities is money that can’t be devoted to capital expenditures, workers, or R&D, or returned to shareholders.

- Costly failures. Incentives often don’t achieve their desired outcomes or even go to companies that later fail entirely. Unused facilities at Fisker in Delaware, Foxconn in Wisconsin, Tesla solar in New York, and many others dot the American landscape, serving as multimillion-dollar monuments to foolish government planning.

- Eminent domain abuse. Business incentives are also often linked to the abuse of eminent domain authority, most famously when the town of New London, Connecticut, bulldozed numerous houses for a Pfizer facility that was never developed (and thanks to one of the worst Supreme Court cases in recent memory, was allowed to get away with it). While many states have since reformed their eminent domain laws to curb abuse tied to “economic development,” not all have—so the problem continues to this day (including near me).

Incentive programs also routinely suffer from other unseen costs associated with federal industrial policy, such as moral hazard, adverse selection, and policy uncertainty—phenomena that can also strain budgets, breed failures, and discourage private investment.

And for what?

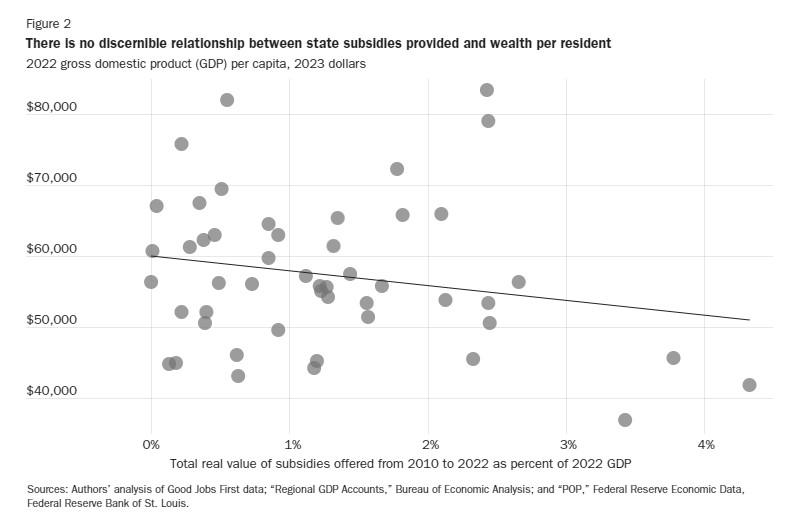

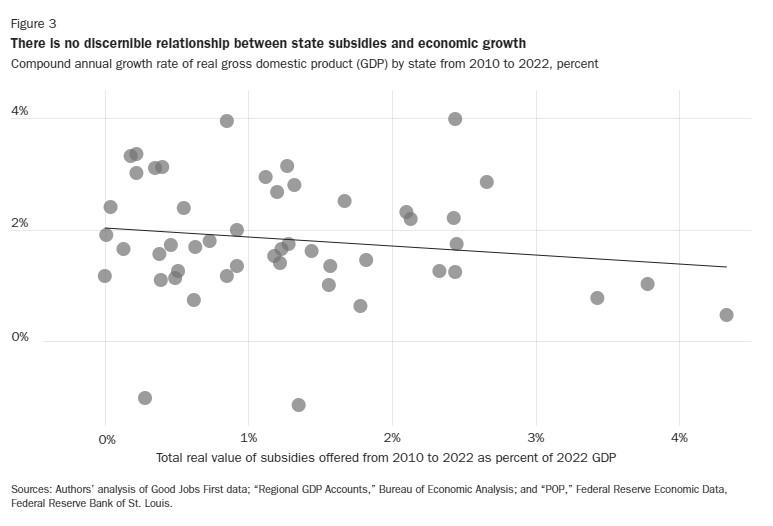

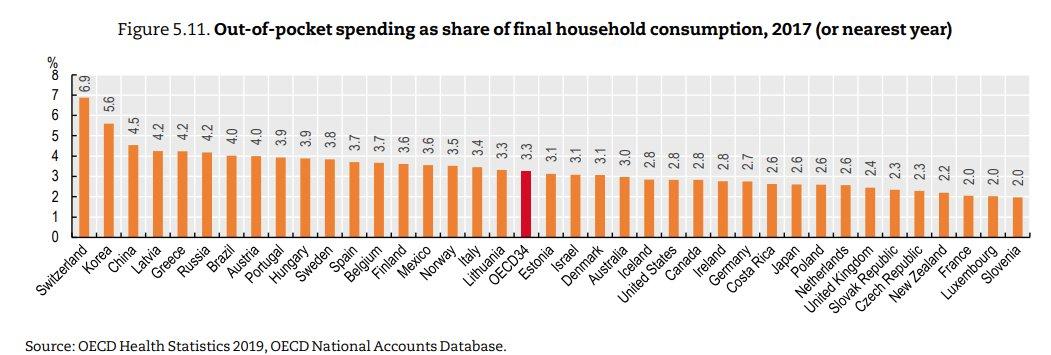

Well, if you listen to local politicians and other subsidy advocates, their pitch sounds a lot like the one made for subsidized sports stadiums: These magical subsidies will get us the company/jobs and all sorts of additional economic benefits that would never happen without the subsidies. Yet concrete and widespread evidence of these benefits ranges from thin to nonexistent. For starters, both academic research and company statements show that subsidies were directly responsible for only a small fraction of local investment decisions. In most cases, governments were simply duped into paying companies to do what they already planned to do, regardless of taxpayer funding. Furthermore, claims that economic development subsidies consistently generate “spillover” or “multiplier” effects for local communities (i.e., economic benefits that far exceed budgetary outlays) have little empirical support. Our own quantitative analysis shows, in fact, no strong relationship between state subsidy levels and economic output or growth. If anything, the relationship runs the other way—states that offer lots of subsidies tend to be poorer and/or grow less:

Rare exceptions do exist, and the correlations above of course don’t mean that subsidies caused the observed economic weakness. But the lack of any clear linkage between economic development incentives and, you know, actual economic development should temper subsidy advocates’ enthusiasm. If corporate incentives were as economically effective as politicians claim—generating big positive economic and social spillovers for a state economy—we’d expect to see a positive correlation between subsidies and wealth or economic growth. We don’t.

So Why Do State and Local Subsidies Persist?

These problems raise the obvious question of why business incentives exist and proliferate, and we see three main reasons. First, the aforementioned lack of transparency makes it difficult for journalists and skeptics to document and quantify subsidies, and thus to hold policymakers accountable for their costs or outright failures. For every much-publicized Foxconn there are dozens of other, smaller failures that never get reported in any systematic way. The data we used for our figures, for example, required hundreds of hours of internet sleuthing through things like news reports and financial statements because official, comprehensive figures aren’t often easily available. And even those totals are surely missing lots of things!

Second, state courts have continuously expanded what elected officials define as a “public purpose,” so that anti-aid or gift clauses in state constitutions no longer bar corporate welfare. As we explain, these constitutional provisions were intended to prevent taxpayer funds from being used for private gain—a term that should include handing out millions to private companies. Instead, public funds were supposed to be used for truly public purposes—roads, schools, parks, etc. However, state governments have consistently expanded the term “public purpose” to be vaguely defined as anything that might plausibly (and indirectly) benefit the general public, including economic development subsidies, and courts have regularly deferred to state legislatures in determining what “public purpose” means. As a result, 46 states have upheld the constitutionality of economic development incentives, thus opening the door wide open to their use.

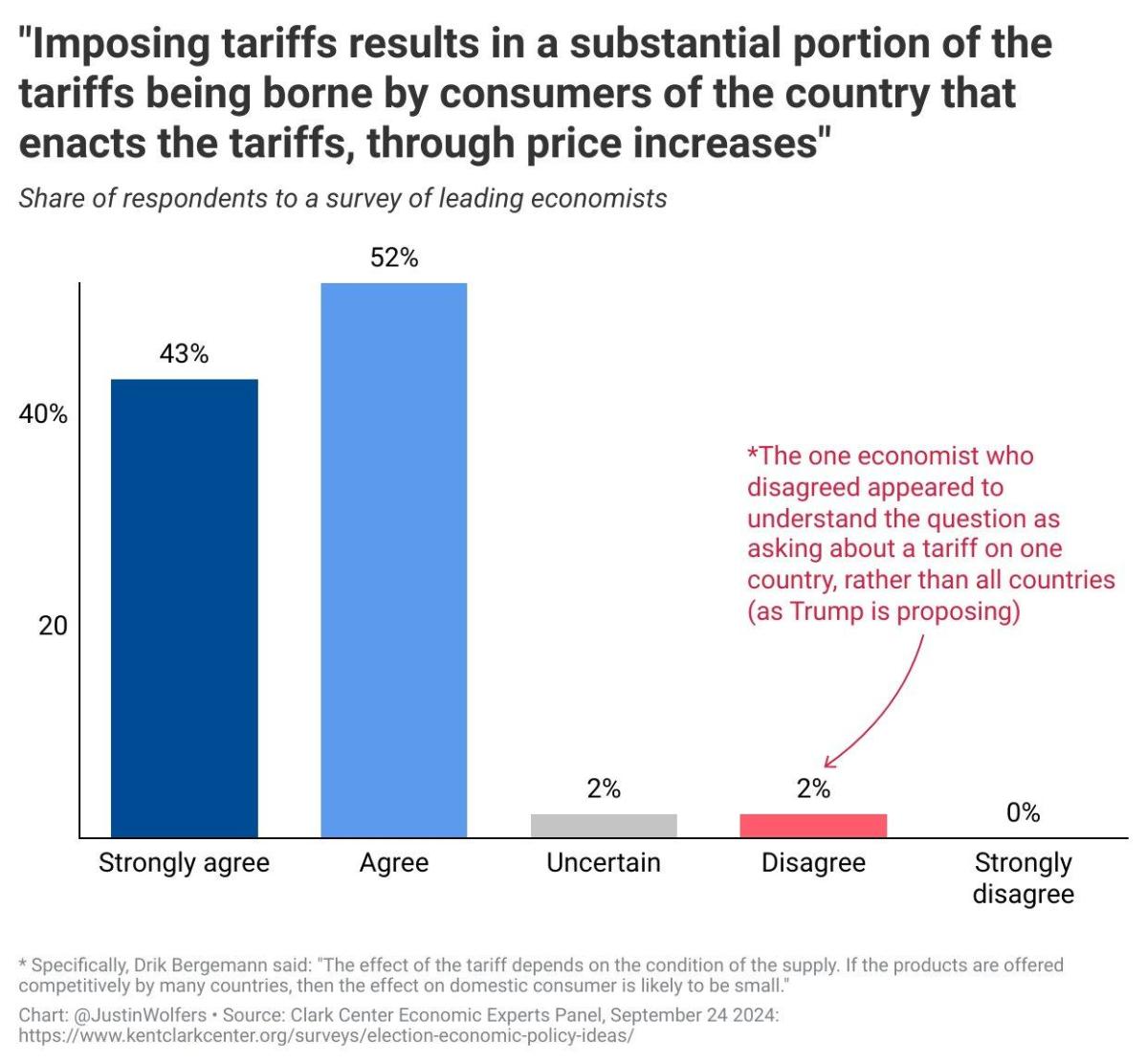

And that brings us to the third, probably biggest, reason why these subsidies persist: politics. As we discussed regarding stadium subsidies, voters tend to support these incentives:

As Bastiat explained almost two centuries ago, most people recognize the visible benefits of government actions while ignoring their invisible costs. Thus, it’s perfectly natural (annoying, but natural) for voters to reward elected officials who provide subsidies that generate tangible and highly visible outputs…while missing those same projects’ many hidden costs, especially opportunity costs like forgone tax revenue and lost economic activity. Research further shows that voters reward politicians for even trying to subsidize stuff (in the study’s case, corporate investment), so politicians have a strong incentive to do just that.

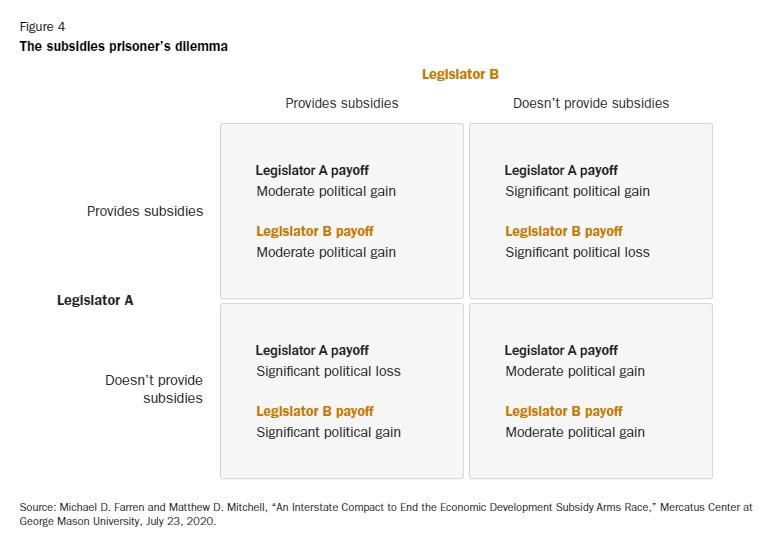

Economic development incentives also present a “collective action” problem for state and local government officials forced to compete against each other for scarce resources (here, corporate investment):

This creates a classic “Prisoner’s Dilemma” situation, in which two guilty prisoners being interrogated by the police would go free if they stayed silent, but, because each can’t be sure the other will keep his mouth shut, both end up confessing to minimize their jail time. Many economists and political scientists have applied this framework to corporate relocation incentives and two hypothetical legislators from different states. The optimal outcome for both would be to withhold subsidies, but because each legislator has no way of ensuring that the other will abstain and because one’s support of subsidies will make the abstaining politician lose votes/support, they both offer subsidies.

These political forces create a “subsidies arms race” among states and localities—one that is difficult, if not impossible, to stop without additional reforms.

The Only Way to Win the Subsidies Game Is Not to Play

Ideally, state and local governments would unilaterally eliminate all corporate tax incentives and subsidies, given their many problems. However, this result is—to put it nicely—highly unlikely in the near term because of all the federal subsidies in play and because the political temptation to continue these economic interventions is so strong. We therefore propose two incremental reforms that would likely limit the use of state incentives by a significant amount.

First, states and localities should enter into compacts to abstain from offering incentives. By assuring local lawmakers that their cross-border rivals will not offer subsidies to entice companies to move to, or remain in, their own jurisdictions, interstate compacts can short-circuit the “bidding war” problem that pervades current incentives policy and related political rhetoric. There are more than 190 interstate compacts in force today, and one is directly on point: Kansas and Missouri have agreed not to issue new subsidies to companies relocating from/to Kansas border counties to/from Missouri border counties. (Sadly, stadium subsidies aren’t covered.) The Coalition to Phase Out Corporate Tax Giveaways, a bipartisan group of state legislators, made a more ambitious effort to stop corporate incentives through an interstate compact, with proposed legislation in 15 states banning “taxpayer dollars to induce a facility in another state that has joined the agreement to move to the offering state.” So far, however, those bills haven’t progressed.

Internationally, meanwhile, the World Trade Organization agreements contain multiple subsidy discipline measures agreed by all 166 member governments, including the United States and all other large, industrialized economies, and incorporated into their domestic laws. These disciplines could serve as a guide for an interstate compact—or series of regional compacts—prohibiting or strictly limiting corporate incentives.

Second, state and local governments should significantly improve their reporting of corporate incentives. Laws should require state agencies to provide lists of all subsidies—grants, tax credits, loans, infrastructure, etc.—with dollar amounts by company, program, and agency in electronic spreadsheet form. They also should include not only the annual cost of an incentive, but also the accumulated cost to date and projected future costs. Finally, a transparency law might also require subsidized companies to report the number of jobs they agreed to create as a result of an incentive package versus the number they actually created (as jobs are a common metric for subsidy distributions and program success).

Of course, the best approach to state and local economic policy is to eschew special deals to individual companies and instead provide a better environment for all companies in the jurisdiction by lowering and simplifying business taxes, reducing regulations, accelerating permitting processes, and undertaking other free market reforms. In the meantime, however, these two reforms would go a long way to stopping the interstate subsidy race that all Americans are unfortunately, unwillingly, and mostly unwittingly playing.

You can read the full paper here.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.