With the U.S. presidential election mere weeks away, tariffs have become a frequent topic of discussion and, unfortunately, an even-more-frequent source of misinformation. (See, for example, last night’s debate.) For that reason, I’ve decided this week to dedicate an entire column to busting the most common tariff myths I see repeated online—and by a certain Republican presidential candidate—each day.

For you Capitolism diehards out there, some of this will sound familiar because we’ve dug into these myths piecemeal in previous columns, so please accept my apologies in advance. (Since you’re getting around 3,000 original words more than 45 weeks a year, however, you’re still probably getting your money’s worth.) Nevertheless, it seems worthwhile and (again unfortunately!) necessary to publish this updated, consolidated version for the non-diehards and, ahem, their many misguided friends.

So, away we go.

Myth 1: Foreigners Pay Protective Tariffs

Perhaps the silliest of all tariff myths is the one Donald Trump keeps repeating. By law, a U.S.-based person or company importing a product into the country will be liable for paying any tariff (tax) owed on that product. In theory, however, the ultimate burden of those taxes—who actually pays—will depend on whether a foreign seller wants to stay in the U.S. market so much that he’s willing to lower his price enough to offset any tariff amount being applied to his product. In the case of, say, a 25 percent tariff on a widget that used to be sold for $100, a foreign widget seller could lower his price to $80 to offset the $20 in new tariffs that a U.S. importer paid when it entered the country, thus keeping the widget’s total price at $100. (American consumers rejoice!) However, if the foreign seller doesn’t lower his price, then someone in the United States will ultimately be paying the tariff (so, $25 on a $100 widget), with no exceptions. (The Tax Foundation’s Erica York patiently walks through these choices in a recent Cato Institute essay.)

How tariffs’ “economic incidence” shakes out in the real world will depend on lots of things, such as an exporter’s profit margins, the type of product, and whether there are reasonable alternative markets or products available elsewhere in the world. And it’s not all or nothing—often importers and exporters share a tariff burden.

For Trump and his fellow American protectionists, however, there are two big problems with the “foreigners always pay” argument. First and foremost, a tariff paid by foreigners can’t also protect domestic manufacturers (like Trump says his tariffs did) because the total import price ($100 in the example above) won’t change after the tariff is applied and thus won’t change the purchasing decisions of still-price-conscious Americans. Thus, George Mason University economist Don Boudreaux explains (emphasis mine):

A protective tariff serves its purpose only if the importer passes on at least part of that cost to its customer. The very purpose of tariffs is to increase demand for domestically produced goods by raising the prices that consumers pay for imports. A tariff that doesn’t raise prices paid by consumers doesn’t protect domestic producers.

You can’t have it both ways.

Second, we now have piles of real-world evidence showing that American companies and individuals bore almost all the Trump-era tariffs’ economic burdens, whether as additional import taxes or higher prices of both foreign and domestic goods (more on the latter in a sec). Along with the many first-person accounts of companies and individuals paying these tariffs and often passing them on to U.S. consumers, York summarizes the extensive economic research showing a “near complete pass-through of the 2018–2019 tariffs”—on steel and aluminum, on Chinese imports, on washing machines, on solar panels—to American companies and consumers.

So, yes, in theory foreigners can pay (indirectly) U.S. tariffs, but not if the tariffs protect American manufacturers. And foreigners most definitely haven’t been paying Trump’s tariffs over the last few years. We have (and probably would do so again).

Myth 2: Protective Tariffs Don’t Increase U.S. Prices

It’s similarly misguided to claim, as some misguided souls recently have, that protective tariffs don’t increase U.S. prices. The basic logic and economics here are again straightforward: If tariffs didn’t increase import prices, then they wouldn’t protect U.S. companies from that foreign competition; and if those U.S. companies were already selling at or below the import price, then they wouldn’t need a tariff to change American importers’ and consumers’ behavior. (Nobody—not even me—is “buying foreign” just for the fun of it.) By forcing importing firms to either pay a tariff or switch to more expensive U.S.-made goods, protective tariffs will push the domestic market prices of those goods higher than they’d otherwise be. If they didn’t, then they wouldn’t protect anything.

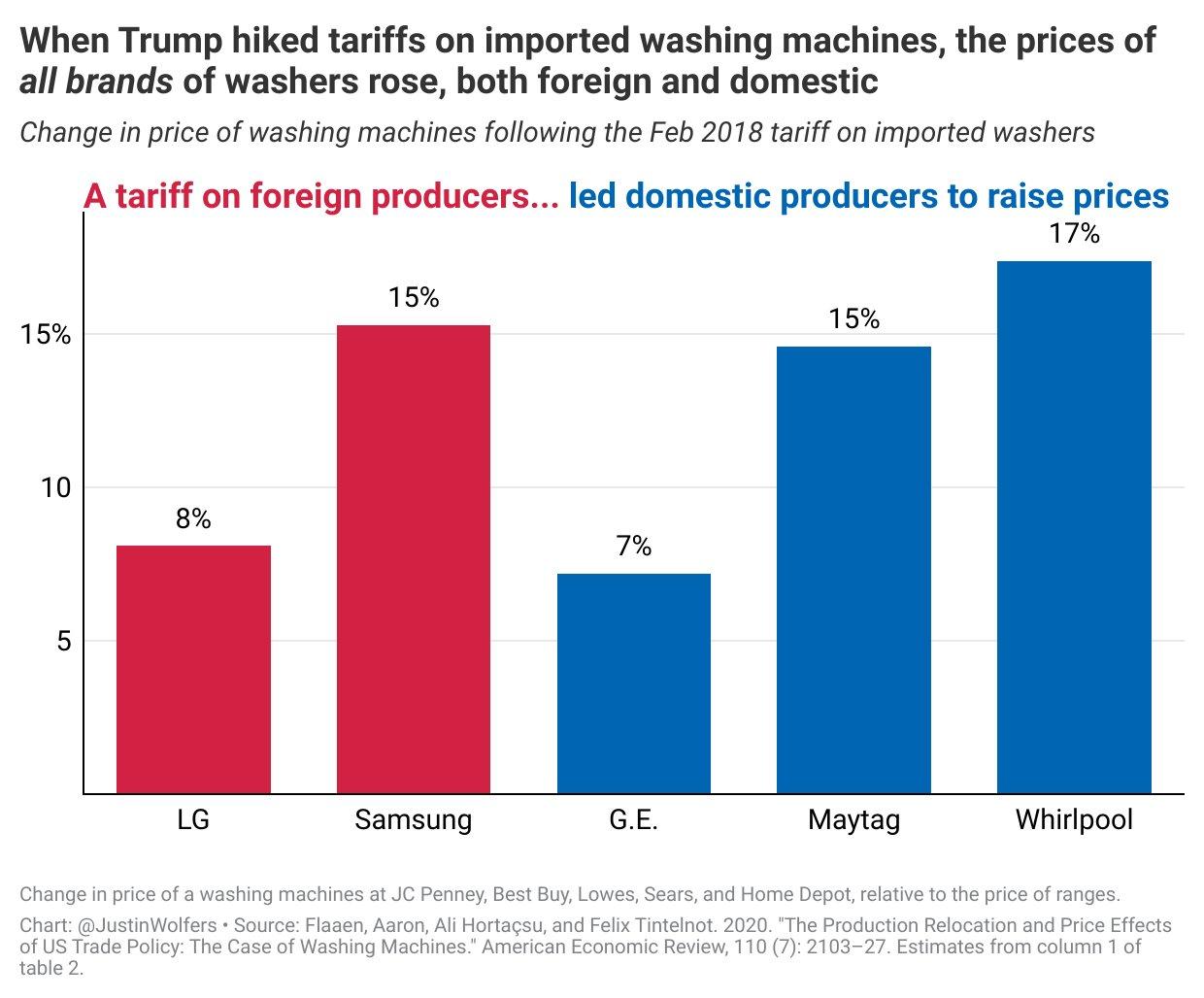

Furthermore, high or unpredictable tariffs can reduce potential supply and give domestic producers more market power over U.S. consumers who, thanks to the tariff, have fewer alternatives, and this can and often does increase the prices of the American-made goods even higher than they were before the tariff. These kinds of price-boosting effects are precisely why U.S. manufacturers—like this guy—lobby for tariff protection. And we see them all the time in the economic data.

For example, Obama-era tariffs on washing machines, a recent paper showed, didn’t raise U.S. prices because they weren’t protective. (Korean companies simply moved to other countries to avoid the tariffs.) Trump-era tariffs on those same goods, by contrast, were global and did significantly raise U.S. prices of both washers and dryers by about $90 each.

The U.S. International Trade Commission’s 2023 review of those tariffs found similar price effects through 2022 and helpfully added that the Trump administration itself expressly defended the tariffs in 2018 on the grounds that they’d increase both import and U.S. prices. (The ITC’s report also helpfully pointed out that the tariffs didn’t save the incumbent U.S. companies that sought protection and instead boosted new Korean-owned factories elsewhere in the country.)

As recently summarized in this blog post, numerous other studies of the Trump-era tariffs—by academics, think tanks, and U.S. government entities—have found that they increased both import and U.S. prices by significant amounts. I even saw this firsthand as an attorney representing U.S. companies that imported and consumed newly tariffed goods and were suddenly facing not only high tariff bills from U.S. customs but also higher price quotes from American alternatives.

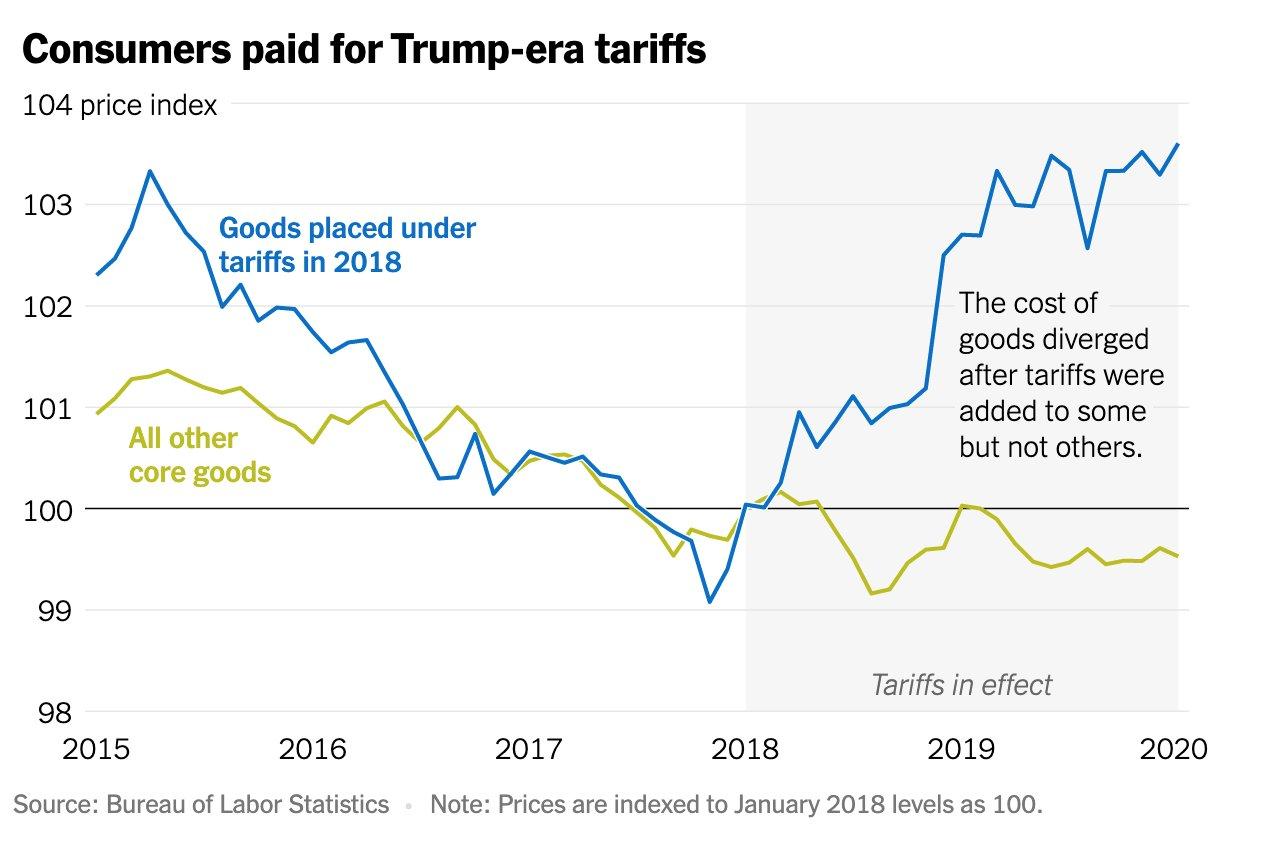

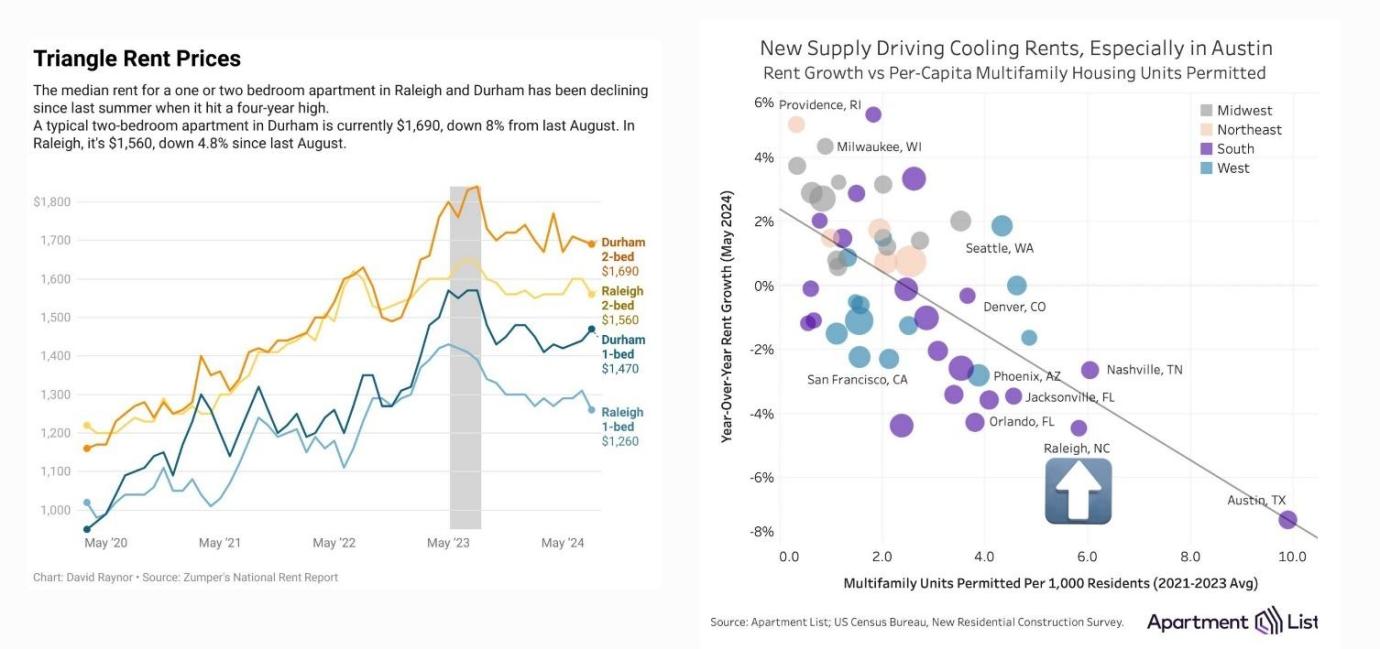

Anyway, here’s the killer chart from Steven Rattner making all of this clear:

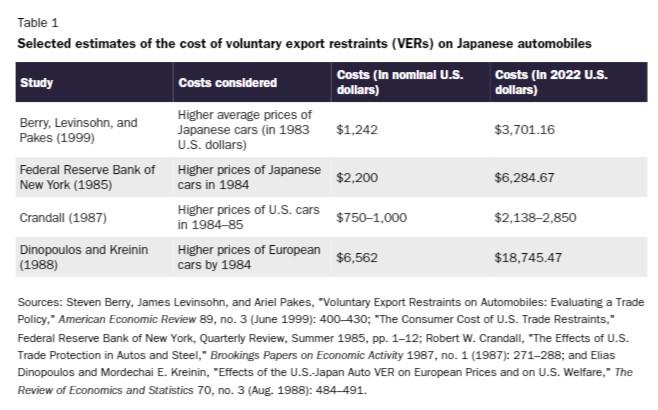

As I wrote in 2017, numerous studies of previous U.S. tariffs and other forms of protectionism, such as for Japanese automobiles during the 1980s, have found similar consumer costs:

Some tariff fans have countered these many studies and claimed that Trump’s tariffs didn’t actually increase prices because inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, was modest during Trump’s time in office, but this argument fails for two reasons. First, U.S. tariffs on specific products won’t increase the price of everything here (aka the “general price level”), as York explains:

When businesses and consumers pay more for tariffed goods, they have less to spend elsewhere, which reduces demand for other goods. Combined with currency fluctuations, that means tariffs primarily affect relative prices, as opposed to the overall price level. And further, the goods that faced higher tariffs comprise a relatively small share of the goods measured in price indexes, meaning that while pass-through [to consumers] was complete, it had a small effect on the overall price level in the United States.

Other things, such as monetary and fiscal policy and the general state of the U.S. and global economies, will also affect inflation and the general price level. Simply citing those superficial stats to defend tariffs’ lack of price effects is thus misleading or misguided. We have rigorous studies of these things for a reason, folks.

Second, whether end-consumers like you and me will see increased prices of tariffed goods depends on whether U.S. companies—importers, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, etc.—pass on the higher prices they’ve paid. In some cases, they don’t. (Maybe, for example, they prefer to maintain market share and thus decide to just eat the tariffs’ cost and accept lower profits.) This can spare American consumers, but—just like corporate taxes—it doesn’t mean the tariffs are costless because the companies paying have less money for hiring, investment, and so on. And none of this changes the simple, basic, and obvious fact that someone in the United States paid more because of a protective tariff. Again, that’s the whole point.

Myth 3: Tariffs Made America Great

This one also continues to get tons of attention even though it, too, has been repeatedly debunked. In short, the actual research on how tariffs affected the 19th century U.S. economy show the issue to be a classic case of correlation versus causation: Because tariffs were high during a period of rapid American growth and industrialization, so the argument goes, the former caused the latter. As economic historian Phil Magness explains in a recent Cato essay, however, such a conclusion is mistaken:

National conservatives often point to the high economic growth of the late 19th-century tariff era as “proof” of the American System’s success; however, this position relies on a misreading of evidence. As economist Douglas Irwin notes, “tariffs coincid[ing] with rapid growth in the late nineteenth century does not imply a causal relationship.” American System proponents failed to articulate the mechanism whereby tariffs contributed to this pattern, amid other complications. For example, many “infant” U.S. manufacturing industries they credit to tariffs began in the comparatively low tariff late antebellum era. Nontraded economic sectors such as utilities also saw faster growth rates and capital accumulation than import-competing manufactured goods in the late 19th century, defying the pattern that the protectionists would predict. Irwin summarily notes that hypothesized “links between tariffs and productivity are elusive.” The claimed correlation with growth is both exaggerated and likely spurious. There’s also evidence that the harms of late 19th-century protectionism outweighed the isolated benefits to selected industries on net. Economist Bradford DeLong identifies two such harms: (1) the loss of agricultural exports to Europe through symmetry effects, effectively harming farmers in order to prop up northeastern industries and (2) higher prices on imported machinery and other capital goods, which likely impaired the pace at which America industrialized.

Economist Vincent Geloso recently echoed Magnus’ conclusion, adding that the U.S. economy was already pretty great by the time its 19th century protectionist experiment began and noting some rather conspicuous cherry-picking by tariff defenders. Other research supports Magness’ and Geloso’s conclusions (findings and research summary at the link). In sum, U.S. tariffs imposed after the Civil War likely helped some American manufacturers and harmed others, but they were generally neither a major driver of nor drag on the sector’s and economy’s growth, which was instead driven by other, bigger factors, such as increasing productivity and an expanding labor force. Leaving aside the many reasons why the 19th century doesn’t tell us much about today’s global economy, the research gives us little other reason to try to repeat tariff history.

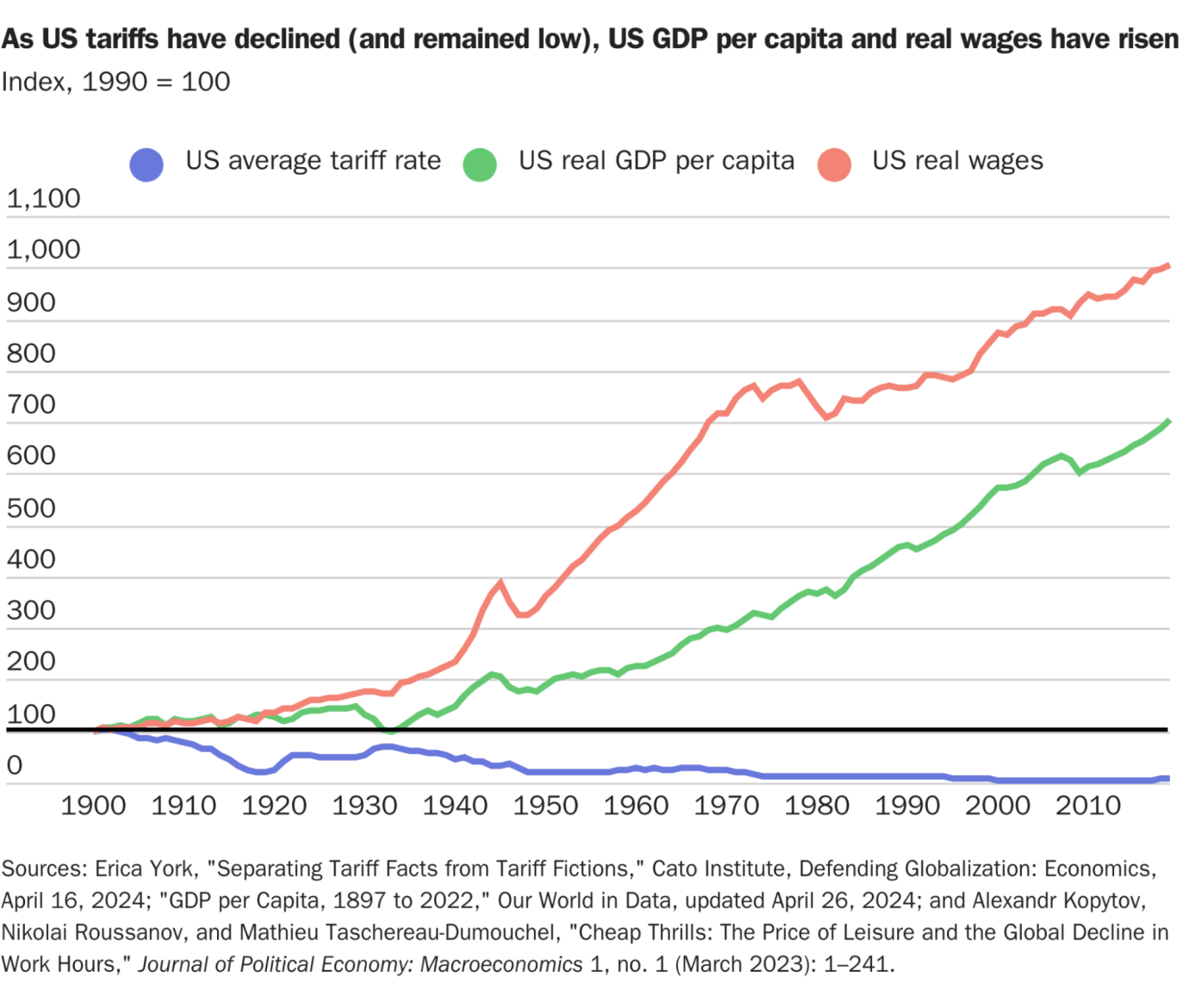

In reality, however, no one should expect tariffs—whether back then or today—to drive the U.S. economy, given all the other, bigger factors at play and the fact that trade just is a relatively small share of economic output. That’s why you’ll find few fans of trade liberalization claiming that it caused the rapid growth of U.S. economy and wages since the early 1900s, even though the former coincided with the latter:

This is, as we’ve discussed, what real economics is for—to look through the fog of superficial correlation and see a policy’s actual effects. It’d be nice if protectionists tried that out sometime.

Myth 4: Tariffs Can Reduce the Trade Deficit

This idea, another Trump favorite, also seems superficially plausible but again withers under scrutiny. York again starts us off with the economic theory:

Almost all [economists] understand that a nation’s overall balance of trade is driven not by trade policy measures like tariffs or free trade agreements but by deeper macroeconomic factors, including national saving, national investment, currency values, fiscal policy, demographics, and international capital flows. Given US and global savings and investment patterns, along with the status of the US dollar as the global reserve currency, the United States has run trade deficits for decades, regardless of tariff levels or other trade policy changes (which do not fundamentally alter the macroeconomic factors within or outside the United States).

In practice, research shows that tariffs can reduce both imports and exports, reducing a nation’s overall level of trade but leaving its trade balance unchanged in the long run. This occurs through four channels: 1) U.S. importers substitute to other countries not subject to tariffs, thus leaving import levels basically unchanged; 2) foreign countries retaliate in response to tariffs, thus reducing U.S. exports; 3) U.S. manufacturers pay more for tariffed inputs that make their products less globally competitive, thus reducing exports; 4) the U.S. dollar appreciates as fewer dollars are on the global market, thus reducing exports (which are now more expensive in foreign currencies). These effects depend on several factors, but in no case would tariffs substantially reduce imports and boost exports, thus trimming the trade deficit.

Even many protectionists agree with this conclusion, and the real-world data support them: Economists have looked at dozens of countries and found no strong, clear connection between tariff levels and trade balances; and, despite all the new U.S. tariffs imposed since 2018, our overall trade balance has barely budged.

Myth 5: U.S. Tariffs Can Boost the U.S. Economy on Net

This is a strange one, but I keep seeing it pop up online. Again, the theory here is clear: Applying a tariff to imported goods would raise its domestic price above the world market price, which helps domestic producers (boosting “producer surplus”) and hurts domestic consumers (reducing “consumer surplus”) while also generating some revenue for the government. However, the standard theory—shown in the graph below—is that the reduction in consumer surplus would exceed the increases in producer surplus and tariff revenue, producing a net loss in economic welfare (aka “deadweight loss”):

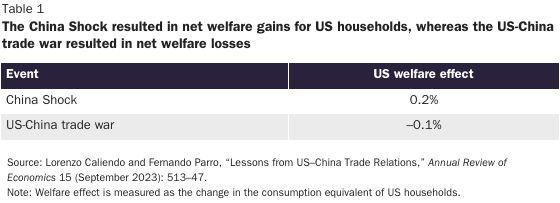

The empirical literature from dozens of countries over many decades again confirms the theory: In case after case after case—and regardless of the model used—economists have found that tariffs reduce national economic output and make a nation worse off on net, while tariff liberalization generally does the opposite. (One of the more popular trade models, if anything, understates the output gains from trade liberalization.) A recent economy-wide analysis of U.S.-China trade shows these diverging outcomes and explains why, even after the “China Shock,” economists remain tariff skeptics:

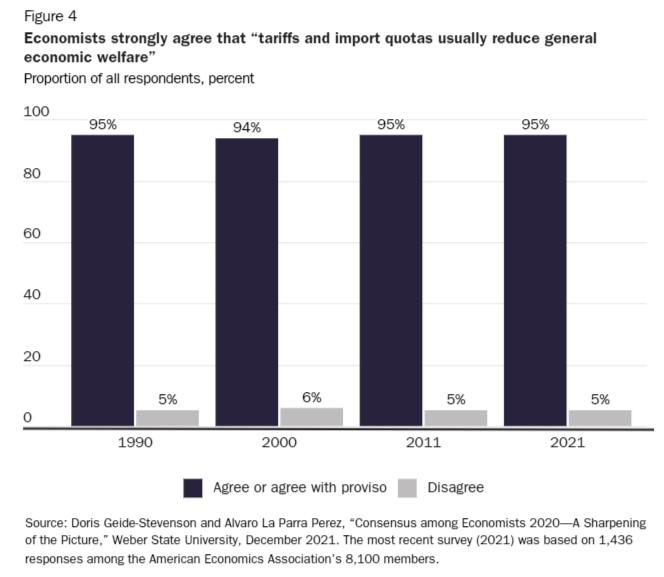

One can plausibly argue that tariffs’ modest economic costs are worth the even more modest gains they generate for certain workers and communities or for national security. (I disagree, of course, in part because small differences in growth really add up over time.) But arguing that the tariffs are themselves net economic winners is a nonsense take peddled by charlatans and overwhelmingly rejected by serious economists on the left, right, and center:

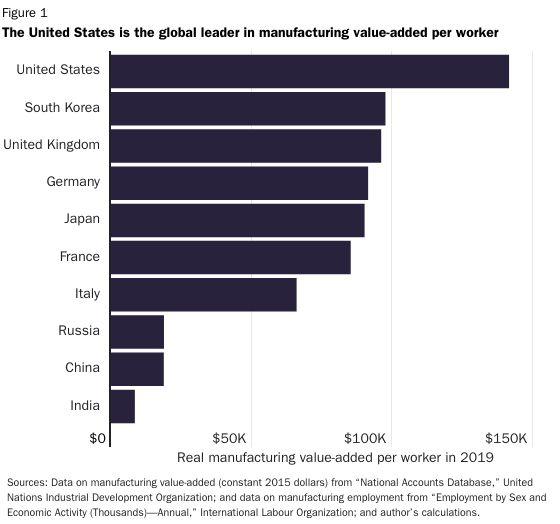

Myth 6: American Manufacturing Needs Tariffs to Compete

Another common claim is that—thanks to subsidies, lax regulations, cheap labor costs, and more—U.S. manufacturers simply can’t survive without tariffs, yet this too is absurd on its face. For starters, even after the Trump/Biden tariffs, average U.S. tariff rates remain relatively low (see below), and yet the U.S. manufacturing sector remains the second largest in the world and is today enjoying record-high industrial capacity. If low tariffs were somehow destroying the U.S. industrial base, they have a funny way of showing it.

In reality, many factors—such as our legal system and geography and a fairly reasonable tax and regulatory climate—support the manufacturing sector’s continued global competitiveness, but two warrant attention. First, relatively high U.S. manufacturing productivity (i.e., American workers produce much more stuff per capita than their overseas counterparts) means American factories can pay more and still beat out lower-wage competitors abroad without the need for tariffs, especially in higher-tech, capital-intensive industries like aerospace:

The U.S. economy’s other big strength here is its continued openness to trade, investment, and people (though this could certainly be further improved!). As we’ve discussed, U.S. policy generally allows American manufacturers to leverage global goods, services, investment, and talent in ways that many foreign manufacturers can’t. Foreign direct investment into the U.S. manufacturing sector is huge and beneficial; our inviting capital markets are the best in the world; and even the dreaded “outsourcing” can help American manufacturers expand their domestic operations and stay at the cutting edge. The United States can’t make everything on its own and can’t be No. 1 in all areas, but we’re doing pretty darn well overall—and we have an open policy environment to thank for much of that.

This also gets to the other reason why tariffs can’t make American manufacturing great today: Around half of everything imported into the United States is stuff used by other U.S. manufacturers to make their products at globally competitive prices. Tax the former, and you hurt the latter—an outcome we just saw with steel and aluminum tariffs, which may have helped some steelmakers (via higher prices, of course) but ended up harming other industries and the manufacturing sector on net.

As indicated above, moreover, tariffs hurt U.S. manufacturers looking to sell abroad—via higher input costs, currency appreciation, and foreign retaliation. A 2020 Federal Reserve paper thus shows that “new U.S. import tariffs in 2018-2019 significantly dampened U.S. export growth” because American companies had higher input costs, and a brand new study finds that Trump’s proposed global tariffs wouldn’t help U.S. manufacturers on net for similar reasons (i.e., “across-the-board tariffs do not protect manufacturing jobs because the cost of imported intermediate goods increases, raising costs in manufacturing production”).

Finally, as economist Scott Sumner recently noted, tariffs would not only decrease imports and exports but “also tilt consumption away from goods and toward services,” thus causing the U.S. economy to eventually shift away from manufacturing to services. Overall, “the goods sector of the economy would be taxed at a much higher rate than the service sector, which would reduce goods as a share of GDP” (i.e., a smaller U.S. manufacturing sector overall).

Free lunches, it turns out, still don’t exist.

Myth 7: America Has No Tariffs, While Every Other Country Has Tons

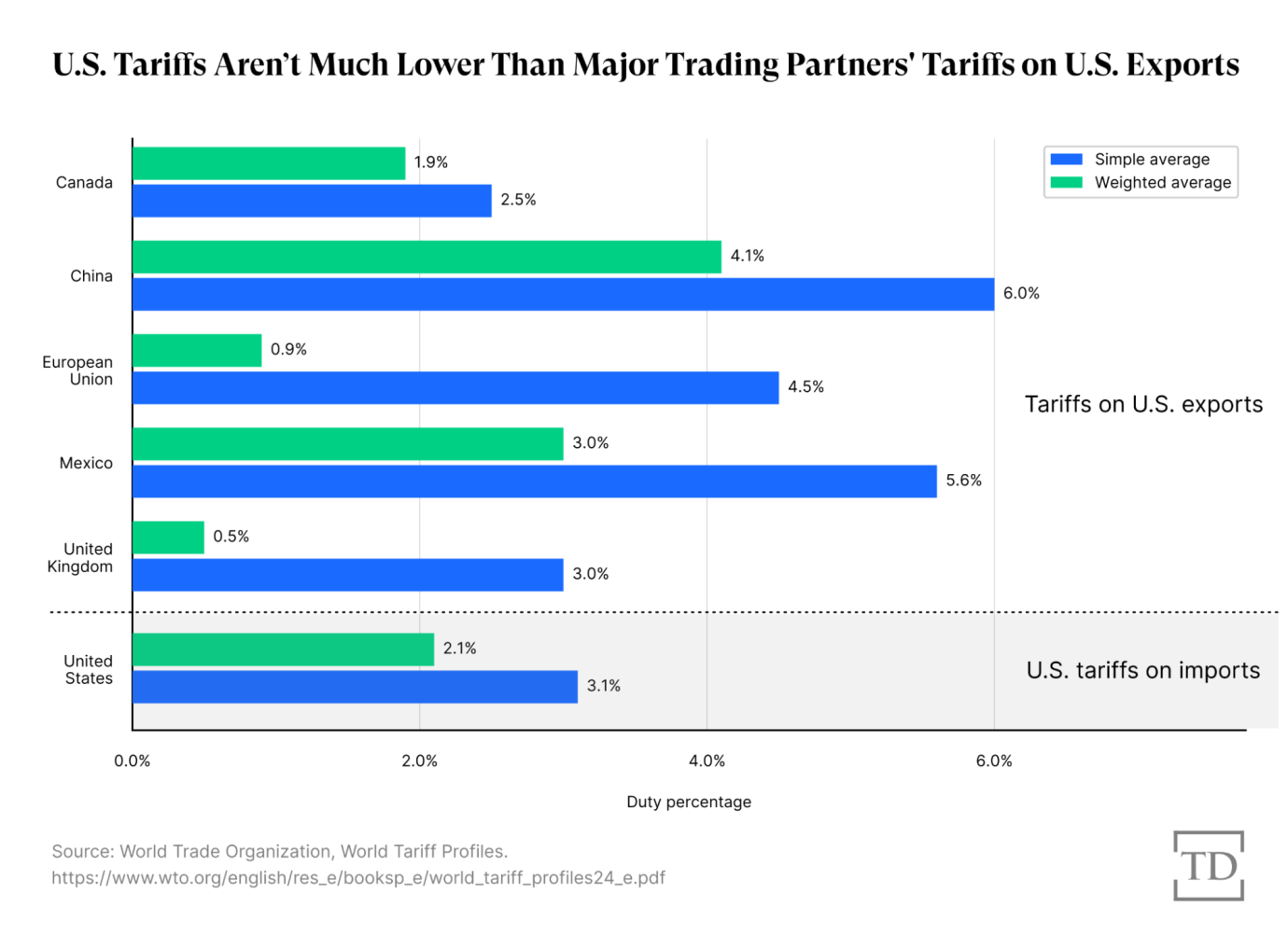

Even some tariff skeptics say this one, but it’s a half-truth at best. First, as the WTO’s tariff database shows, the United States has relatively low average tariffs but still applies high ones on lots of products, including certain foods, textiles and apparel, footwear, and other manufactured goods. In many cases, U.S. tariffs on these “sensitive” items are higher than those applied on the same U.S. goods in foreign markets. The WTO data also show that U.S. manufactured goods exports to our top five trading partners (Europe, Canada, Mexico, China, and the U.K.) in several cases face average tariffs at or below the average tariff rates (2.1 percent weighted average or 3.1 percent simple average) that the United States applies on imports. In the rest, the differentials just aren’t really big enough to get all worked up about.

Overall, World Bank data show that dozens of countries—developed and developing, big and small—have lower average tariffs (simple or weighted) than the United States does. We’re simply not some “free trade fundamentalist” outlier.

Even this benign comparison, however, overstates the “unfair” situation the United States supposedly faces because Washington uses many “non-tariff” measures to impede foreign competition. This includes subsidies, quotas, “Buy American” restrictions, the Jones Act (drink!), and regulatory protectionism like the FDA’s blockade on baby formula. We’re also one of the biggest users of “trade remedy” measures (anti-dumping, especially) and today apply more than 700 special duties on mainly manufactured goods like steel and chemicals.

It’d be great if foreign countries eliminated their trade restrictions, and U.S. trade agreements have been pretty effective in this regard. But given economic harms that U.S. tariffs impose upon Americans, there’s little good reason to wait around for other nations to do what we should be doing regardless.

Myth 8: Tariffs Are Good and Effective Negotiating Leverage to Achieve Real Free Trade (and That’s All Trump Wants)

And this brings us to the penultimate tariff myth of the day, that the United States can effectively use tariffs to create a world of “true” free trade (or something). Start with the most obvious three facts: 1) Trump-era tariffs are mostly still here (in original form or as still-restrictive “tariff rate quotas”); 2) no countries lowered their tariffs in response to new U.S. tariffs; and 3) several countries—China, Russia, the EU, India, Turkey, Canada, Mexico, etc.—actually retaliated with even higher tariffs on U.S. exports. (Some, such as Canada and Mexico, later removed their retaliation in response to the U.S. removing its steel and aluminum tariffs, but tensions persist.) As the National Taxpayer Union’s Bryan Riley notes, analysis of this retaliation shows that “a one percentage point increase in foreign tariffs was associated with a 3.9 percent reduction in U.S. exports.” So, Trump’s last tariff experiment got us less trade, not more, and we’re still paying for it.

These results are typical and just what I and others—ones not named Peter Navarro—predicted before the Trump-era tariffs were implemented. As I wrote years ago, history shows that U.S. tariffs and other protectionist measures have proven to be poor tools for opening foreign markets, doing so just 17 percent of the time they were used between 1975 and 1994. That’s because very few countries are dependent on the U.S. market (or the U.S. security umbrella) and because all of them are run by government officials who will prioritize their own domestic interests—economic and political—when new U.S. tariffs arrive. A failure to respond to those tariffs in-kind risks not only more tariffs but the appearance of geopolitical weakness before their own voters (and thus potential defeat at the ballot box). As one Canadian official just warned regarding Trump’s new tariffs, “Inevitably our government will be under enormous pressure to reciprocate. … So then we have a 10 per cent tariff on that volume of trade on American goods coming into our country, which is not particularly constructive.” Or as EU trade commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis put it, “We defended our interests with tariffs and we stand ready to defend our interests again if necessary.”

Yes, retaliation will hurt foreign officials’ economies and not everyone will retaliate, but many will because the political and strategic benefits of doing so will be viewed as far outweighing the economic and geopolitical costs.

Myth 9: Tariffs Can Replace the Income Tax

Nope.

Summing It All Up

An intellectually honest pro-tariff case would go something like this: Yes, U.S. tariffs have real and significant economic and geopolitical costs on net, but those costs are a necessary price Americans must pay to achieve a core federal government objective (typically national security). I do occasionally see this argument when it comes to China, but in general it’s most definitely not what most American protectionists are offering today. Instead, tariffs are a magical policy that’s all benefits and no costs. They protect American jobs and security, boost industry and innovation, and advance our strategic interests abroad with both enemies and allies alike. We can use them to solve any problem—even child care and the national debt!—and, perhaps best of all, foreigners will foot the bill.

You don’t need a Ph.D. to see some of the flaws in these claims. Think about this stuff for more than a second, and problems emerge: If tariffs make us money and boost the economy, why stop at 10 or even 20 percent? If tariffs don’t raise prices here, then how do they protect American workers from “predatory dumping” or “cheap labor” (or whatever)? If tariffs achieve Real Free Trade, then why do we still have so many in place, some for literally centuries? And on and on. Most of the myths shrivel in the dimmest of sunlight, yet they persist if not flourish. We thus shouldn’t expect that today’s dose of sanity will put an end to the nonsense—where demand exists, supply will follow—but hopefully it’ll make responding a little easier.

Chart(s) of the Week

No links this week, folks. Sorry.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.