Happy Sunday, happy September, and happy Labor Day weekend. Pronatalist arguments—that in order to be a well functioning society we need to be having more babies—are nothing new. But the resurfacing of Ohio Sen. J.D. Vance’s 2021 “childless cat lady” remarks has added a new, overtly partisan dynamic to the conversation.

Few religious Americans would argue that having more children won’t have positive effects for society as a whole, but today Hannah Anderson argues that our reasons for having children matter: Do we think having children is good because they help us right what we might regard as a wayward societal ship? Or is having children good because … it’s good to have children?

Anderson’s argument is a bit more substantive than that, and the words “grace and hope” factor prominently. On that point: Before my wife and I said “I do,” folks told us being married would reveal to us our own selfishness in spades. That was true, but in that regard, being a parent has eclipsed marriage (which before we had kids felt more like an 24/7 honeymoon with jobs thrown in). My own mistakes in parenting my four kids have underscored my often errant understanding of God. At times I am unloving or unkind to my children because in my folly I take him to be unloving or unkind. Other times I am too removed or uninvolved because I fail to see how much he cares for his people.

That’s why I appreciate what Anderson writes about bringing tiny people into this world and caring for them as best you can: It must be shot through with grace and hope, not agendas and culture-warring.

Hannah Anderson: The Unbearable Lightness of Choosing Children

For a campaign full of surprises, the 2024 presidential race has consistently returned to the question of reproduction and family formation. For Democrats (and, well, Republicans now too), the 2022 Dobbs Supreme Court decision offers a clear rallying cry to protect abortion access as well as IVF and other fertility treatments. Meanwhile Republicans are working to project themselves as the party of “family values” claiming that the left is anti-family and anti-children.

Looming behind the politicization, however, is a larger question about the role children play in our collective future—especially as birthrates continue to fall. In their recent book, What are Children for? On Ambivalence and Choice, co-authors Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman argue that children are no longer “self-evident” in the modern West. Instead, having children is now a choice that individuals must make. Additionally, the modern need to construct and project identity affects how we choose whether to have children. They, like us, must justify their right to exist. They must “make sense.” They must be “valuable.” At the very least, they must prove themselves worthier than other endeavors we might undertake with our lives.

Such utilitarian rhetoric is unsettling, but it is particularly insidious when it emerges from religious conservatives under the guise of “family values.” While the left weighs the choice to have children against questions of the fair distribution of resources, climate change, and even competing visions of feminism, some on the right advocate for children as a means of preserving a religious or conservative influence on society. As GOP vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance argued during his now infamous “childless cat ladies” interview:

The entire future of the Democrats is controlled by people without children. And how does it make any sense that we’ve turned our country over to people who don’t really have a direct stake in it? ... If we want a healthy ruling class in this country, we should invest more, we should vote more. We should support more people who actually have kids, because those are the people who ultimately have a more direct stake in the future of this country.

Simply put, children are good for the cause.

But such arguments invariably reduce real persons with real souls to political abstractions. At the time of Vance’s original comments, writer Elizabeth Breunig warned that once children become political talismans of the culture wars, they will not “retain their own essence for long; instead, they become symbols of other things—means to ends instead of ends in themselves.” In the same way, accusations against the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 as a real-life Handmaid’s Tale resonate with many people—not because it would actually force women to become surrogates, but because its underlying utilitarianism frames children as political commodities. Much of its policy is predicated on the assumption that “families comprised of a married mother, father, and their children are the foundation of a well-ordered nation and healthy society” (emphasis mine). It’s one thing to place the burden of the nation’s well-being on responsible adult citizenship, and another thing entirely to expect children by their mere birth and existence to carry that weight as well.

The danger of this kind of commodification is well-known to a particular type of “exvangelical” who grew up in the “Joshua Generation,” a movement predicated on the idea of raising up a generation of children who as adults could drive conservative values in the public arena. The movement overlaps with the QuiverFull Movement (as represented by the reality TV stars Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar) in which married couples forgo birth control for the purpose of having large families. The “quiver” in “Quiverfull” is based on a literal and over-actualized meaning of Psalm 127:3-5:

[Children] are indeed a heritage from the Lord,

the fruit of the womb a reward.

Like arrows in the hand of a warrior

are the [children] of one’s youth.

Happy is the man who has

his quiver full of them.

He shall not be put to shame

when he speaks with his enemies in the gate.

Now adults, those raised in these frameworks must wrestle with the possibility that they owe their existence not simply to the overflow of intergenerational love, but to a culture war.

In writing about the larger ambivalences toward childbearing, Christine Emba argues that none of the conventional explanations actually explain falling birthrates. While public policy and economic realities can make it either harder or easier to support a family, they alone cannot convince someone to have children. Instead, she suggests that the real problem is one of meaning, an uncertainty “about the value of life and a reason for being.” Vance and culture war pronatalists would likely agree, but they seem to find this meaning in the future and the struggle for cultural power. In his framework, those most committed to the well-being of the community’s future are those who choose to have children.

But framing the question of children as a choice may reveal an even larger paradox of modern life. While a woman may choose to become pregnant or choose to end a pregnancy—and fight for the right to do so—none of us come into the world through our own individual choice. Barring infertility, we have the “choice” to reproduce or not because someone else made a choice to reproduce before us. In the very act of creating, we confess that we ourselves were created. In giving life to another, we testify that our own life is a gift.

If our ambivalence toward children is actually rooted in a misunderstanding of our own origins and existence—of understanding life through the lens of choice rather than grace—then the meaning we’re seeking comes to us not only in the future. It also has already come to us in the past. Having forgotten the grace of our own begottenness, we forget how to beget.

Identifying the role that the past has on the present helps explain why pop pronatalism can appeal to those who come from familial instability as well as how it can accompany dramatic religious conversion and personal upheaval. Vance himself came on the national scene through his book Hillbilly Elegy, in which he explored his roots in broader Appalachia. In it, he paints a picture of economic struggle, disenfranchisement, social and relational dysfunction, and childhood trauma. But Vance’s story is also one of “getting out” and making his way up the social ladder through the military, Yale, his conversion to Catholicism, and eventually as a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, U.S. senator, and vice presidential candidate. Ultimately though, his is a story of struggle and survival, of utilitarian scarcity. That his own pronatalist vision takes the same tenor, focusing on rewarding individual choice and promoting the strategic survival of a particular cultural vision, is completely unsurprising.

But grit and survival are not grace and hope. And this distinction may explain why unhealthy religious communities that view children as a means to an end can get pronatalism so wrong even while healthy ones incubate the values necessary to welcoming children into existence. Healthy religious communities hold—in some basic form—a sense of humility at the mystery of life and the need for a grace that comes from outside oneself. They preserve categories of hope and dependence, ideas that Scripture often expresses through the motifs of birth and childhood.

In fact, the Christian story begins with the miraculous appearance of human life out of the overflow of a God who creates in the image of the One who exists in loving communion. But the story of the Scripture also moves forward by improbable birth after improbable birth. This divine inbreaking culminates in the most improbably grace-filled birth of them all, that of Jesus of Nazareth, and continues on by framing the grace-shaped life as a “new birth.”

Because, in the end, it is the improbability of birth and continued human existence that confirms it as a grace even as we remain either ambivalent or try to co-opt it. After all, “be fruitful and multiply” was quickly conditioned by “in pain you shall bring forth children” and “by the sweat of your face.” The degree to which we assume that life and existence rest in our choice belies our modern surfeit and exposes our ingratitude. Having forgotten that our own lives are a gift, we presume upon future ones. Because without a personal experience of the grace and hope at our own existence, we will use their existence to justify our own. Their lives will become the means by which we validate our own and in doing so, we will create the same questions in them.

This is why Scripture also teaches that we enter God’s kingdom as little children. Instead of capturing the kingdom through strength, we become small and dependent. We acknowledge our own helplessness and entrust ourselves to God and others. We remember the grace of our own begottenness, and thus learn to extend this grace to others.

In the end, the flourishing of the human species rests not on biological or political strategy, but on grace and hope—that is, the cultivation of the human soul. It rests on cultivating gratitude, humility, faith, and love because these are the things that make us uniquely human. In other words, our ability to pass on the inheritance of being made alive in God’s image rests on living in God’s image now.

Jordan Ballor: The Public Square Need Not Be Naked

Two weeks ago in Dispatch Faith, Paul D. Miller argued it’s perfectly fine for Christians or others to “vote your values,” but it’s a misunderstanding of the role of government to expect the state to promote any one group’s religious values over others. Today on the site, Jordan J. Ballor responds by arguing the state’s promotion of certain metaphysical values isn’t tantamount to government establishment of religion. Here’s an excerpt:

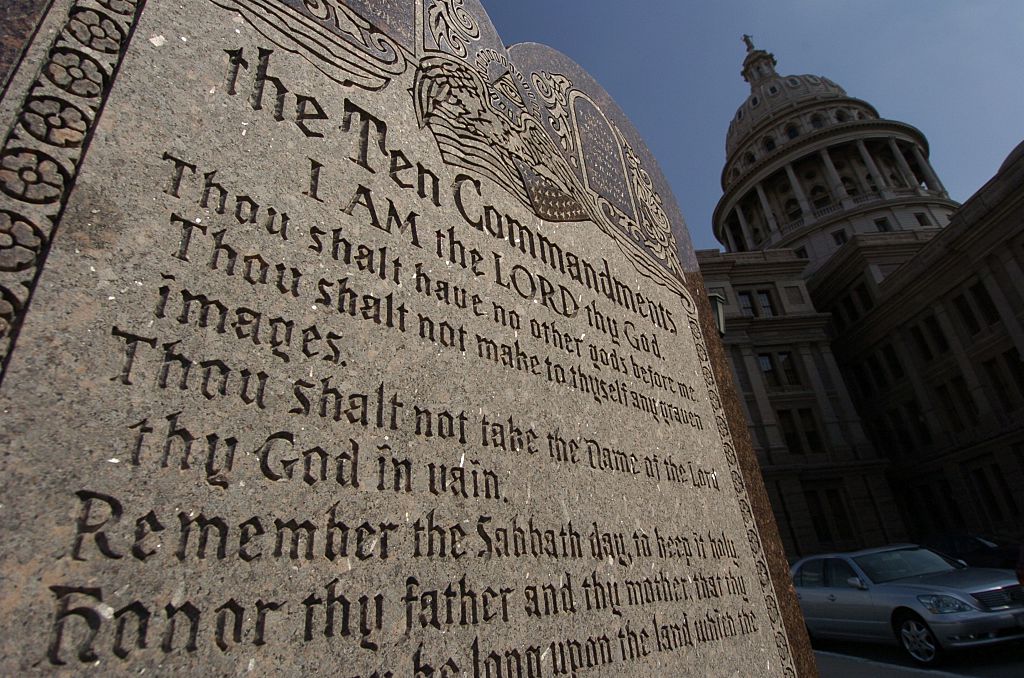

Public display of the Ten Commandments by governments or government agents isn’t necessarily a violation of the establishment clause or a corruption of Christian conviction. But as Mark David Hall perceptively points out, merely posting the commandments isn’t the same as teaching them either, and it really does matter how such public displays, mandates, and expressions are used. They can be used appropriately as well as inappropriately. This certainly calls for a kind of civic wisdom that is sorely lacking in our times.

And if it is true that there are indeed many possible and legitimate ways to avoid the extremes of Christendom and secularism, then the American federal system is a major strength in discovering ways to live together in a pluralistic world. We can enjoy a diversity of experimentation and expression of religious faith in public in different ways in different jurisdictions. What works for Louisiana (or some places in Louisiana) might not work elsewhere, just as what works in San Francisco might be wrong for Sacramento, Spokane, or Sarasota. The American experiment in ordered liberty manifests in these different “laboratories of democracy” rightly constituted as open and free to such exploration. This is something to be celebrated rather than squashed under a mistaken commitment to a mythical secularist neutrality, especially as conceived of as the only alternative to a stifling Christendom.

More Sunday Reads

- The term “postliberalism” gets bandied about quite a bit in public discourse these days, including in this very newsletter. But what exactly is it? Earlier this week we published James Patterson’s explanation of postliberalism and its overtly Catholic roots. “Put simply, postliberalism is three things,” he writes. “First, it is an authoritarian ideology adapted from Catholic reactionary movements responding to the French Revolution and, later, World War I. Second, it is a loose international coalition of illiberal, right-wing parties and political actors. Third, it is a set of policy proposals for creating a welfare state for family formation, the government establishment of the Christian religion, and the movement from republican government to administrative despotism. The third point might sound unhinged, but postliberals have come to object to liberalism. While most Americans know the term ‘liberalism’ as a reference to a left-of-center ideology common among Democrats, the other common use is in reference to a political theory that prioritizes individual rights as a source of political authority and human flourishing. Postliberals believe this ‘classical liberalism’ to be a disembodied secularizing (even satanic) force that uses the language of liberty of conscience, representative government, and constitutionalism to conceal the true liberal aim of denying the authority of the highest good.”

- Season 2 of The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power debuted on Amazon Prime this week, and co-showrunner J.D. Payne talked with Trent Toone of Church News about what it’s like to cling to his faith as a Latter-day Saint while working in Hollywood. “First, his mission provided Payne with ample opportunities to meet interesting people and discuss things that motivate and matter in life. ‘You are getting a window into people’s souls and what makes them tick, and that’s what drama is all about,’ he said. Each week on his preparation day, Payne documented his experiences in lengthy letters home,” Toone wrote. “He’s not sure why, but Payne is often asked by others how to stay firm in the faith while working in the entertainment industry. He says he has always been upfront about his Latter-day Saint beliefs, and now his co-workers won’t allow him to work on Sundays even if he wanted to. He advises others to not be ashamed of the gospel of Jesus Christ, but to be straightforward about it. ‘Hold on to your faith. Don’t be embarrassed of your faith,’ he said. ‘Your faith is part of what makes you unique.’”

A Different Kind of Sunday Show

For this week’s Dispatch Faith video podcast, Paul Miller and Jordan Ballor joined me for a lively discussion about their aforementioned essays on religious values and the state. There were plenty of points of agreement, but also enough friendly disagreement to illuminate the contours of their arguments. Head over to our YouTube channel to check it out and pass along.

A Good Word

Vilnius, Lithuania, was once a focal point of Jewish culture in Eastern Europe, before the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich. Now the capital city is part of a Yiddish renaissance as more and more people seek to learn the traditional language of Ashkenazi Jews. For Religion News Service, David I. Klein reports on efforts in the city to help Jews now scattered around the world who are interested in connecting with their heritage. “Some of the new interest in Yiddish was prompted by the pandemic, when Jews were stuck at home and remote learning opportunities proliferated. The Washington Post has also reported that rising antisemitism has driven many Jews to reexamine their relationship with Yiddish. ‘Yiddish connects me to my roots, helping to restore the cultural transmission from my father that was interrupted by the Holocaust,’ said Mendel Salik, a British-born Jew living in France. ‘I get joy from reading Yiddish texts with their portrayals of bygone Jewish societies with their daily struggles against poverty or persecution and their rich observations of human life distilled into proverbs.’ Vilnius allows Yiddish students the opportunity to walk the same streets trod by some of Yiddish literature’s biggest names, such as Moshe Kulbak and Avrom Sutzkever, the bard of the Vilnius ghetto.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.