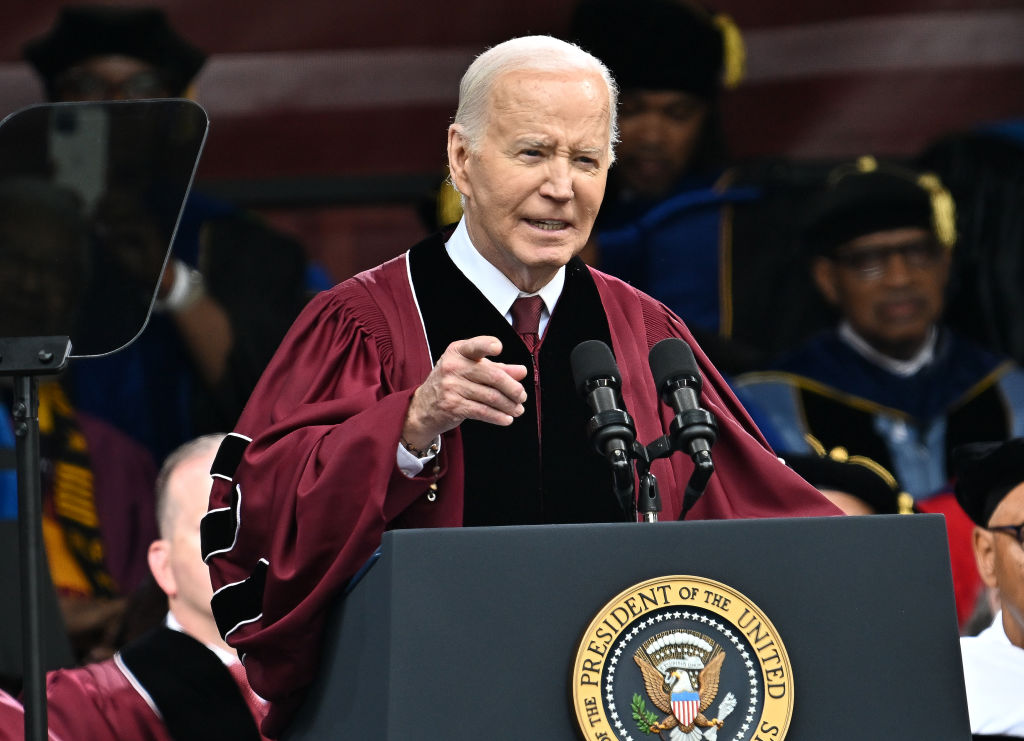

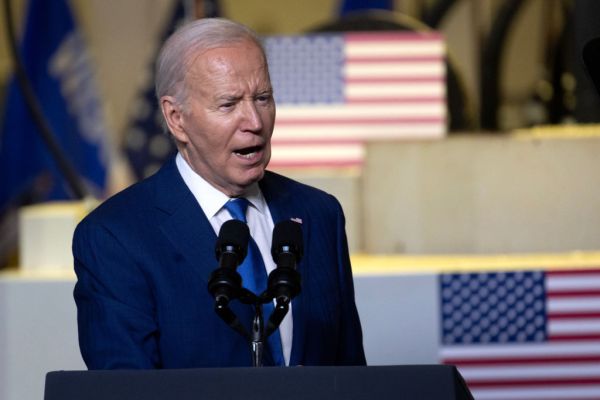

In a commencement speech at Morehouse College, a historically black men’s college in Atlanta, President Joe Biden recycled a long-debunked claim that voters in Georgia cannot access drinking water while waiting to vote. “But let’s be clear what happens to you and your family when old ghosts in new garments seize power, extremists come for the freedoms you thought belonged to you and everyone,” Biden told the crowd. “Today in Georgia, they won’t allow water to be available to you while you wait in line to vote in an election. What in the hell is that all about? I’m serious. Think about it.”

While there are restrictions in Georgia on the distribution of items like food and drink—often referred to as “line warming”—within a certain distance of polling places and voters, these limitations are designed to prevent interference by political organizations. They still allow for self-service water stations.

Spurred by electoral fraud claims in the state’s 2018 and 2020 elections, the provision in question was enacted as part of Georgia Senate Bill 202 (SB 202), an omnibus package of elections legislation passed in March 2021 that sought to “address the lack of elector confidence in the election system on all sides of the political spectrum, to reduce the burden on election officials, and to streamline the process of conducting elections in Georgia by promoting uniformity in voting.” According to Section 33 (a) of the bill, “No person shall … give, offer to give, or participate in the giving of any money or gifts, including, but not limited to, food and drink … on any day in which ballots are being cast: (1) Within 150 feet of the outer edge of any building within which a polling place is established; (2) Within any polling place; or (3) Within 25 feet of any voter standing in line to vote at any polling place.” Section 33 (e) additionally stipulates that: “This Code section shall not be construed to prohibit a poll officer from … making available self-service water from an unattended receptacle to an elector waiting in line to vote.”

The state notably faced claims of voter suppression in 2018 by Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, who refused to concede to Republican Brian Kemp despite losing by almost 55,000 votes. Two years later, Georgia found itself at the center of President Donald Trump’s 2020 electoral fraud claims, which led to the eventual indictment of 19 individuals, including Trump, on charges including racketeering and solicitation of violations of a public officer’s oath of office.

The bill’s passage led to criticism from many left-leaning politicians and activist organizations, who argued that its provisions disproportionately targeted minority communities and would suppress voter turnout. Biden criticized its restrictions at the time in an official statement, writing that the bill “adds rigid restrictions on casting absentee ballots that will effectively deny the right to vote to countless voters,” and describing its provisions as “Jim Crow in the 21st century.” As was reported by TMD at the time, these accusations of voter suppression were disingenuous and misleading:

But attempts by prominent Democrats—including the president—to tie SB 202 to the Jim Crow era are incredibly disingenuous. For starters, the bill actually expands voting access for most Georgians, mandating precincts hold at least 17 days of early voting—including two Saturdays, with Sundays optional—leading up to the election. Voting locations during this period must be open for at least eight hours, and can operate between 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. Several states (including Biden’s home state of Delaware, which will not implement it until 2022) do not currently allow any in-person early voting, and plenty, like New Jersey, offer far fewer than 17 days.

Despite Biden saying the bill implements absentee voting restrictions that “effectively deny” the franchise to “countless” voters, SB 202 leaves in place no-excuse absentee voting with a few tweaks. It tightens the window to apply for an absentee ballot to “just” 67 days, and mandates applications—which can now be completed online—be received by election officials at least 11 days before an election to ensure a ballot can be mailed and returned by Election Day. The bill requires Georgia’s secretary of state to make a blank absentee ballot application available online, but prohibits government agencies from mailing one to voters unsolicited—and requires third-party groups doing so to include a variety of disclaimers.

In August 2023, a federal judge ruled narrowly to eliminate the bill’s restrictions on distributing food and water in the 25-foot “supplemental zone” around voters. The ruling maintained the bill’s limitations within the 150-foot “buffer zone” around polling stations.

If you have a claim you would like to see us fact check, please send us an email at factcheck@thedispatch.com. If you would like to suggest a correction to this piece or any other Dispatch article, please email corrections@thedispatch.com.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.