As frequent Capitolism readers surely know, I’m a big fan of remote work for personal and professional reasons. On the former, I’ve worked from my home in Raleigh, North Carolina, since 2010, and I’m sure it’s helped me live a better, richer, saner life outside of Washington. Most importantly, it’s allowed me to experience far more of my daughter’s life than I would’ve if working in (and commuting to) a D.C. law or policy job every day. On the professional side, I think remote work not only helps millions of American workers enjoy the aforementioned personal benefits, but also can be good for companies and the economy more broadly—and not just because it tends to produce happier workers.

As I wrote in a chapter of my recent Cato book, remote work helps employers—especially newer and smaller ones—expand their pool of potential workers, retain the workers they already have, and lower their commercial real estate costs. It can also help workers and employers find better, more productive matches and can boost employment among formerly marginalized workers—outcomes that are good for both the people involved and the broader U.S. economy.

When I wrote that book chapter in mid-2022, however, the future of remote work was cloudy: Data on its effects and durability were limited; pandemic-era restrictions were (mostly) gone, thus eliminating some of the remote work necessity; companies and workers were still figuring out such details as the proper balance between home and office; and some employers—especially at big, highly visible companies—were calling their workers back into the office full time. All of those factors made whether we were reverting to the old normal or experiencing a new one an open question.

Today, however, we have a lot more information, and it’s increasingly clear remote work is here to stay—and mostly for the better.

Remote Work Levels Remain Steady

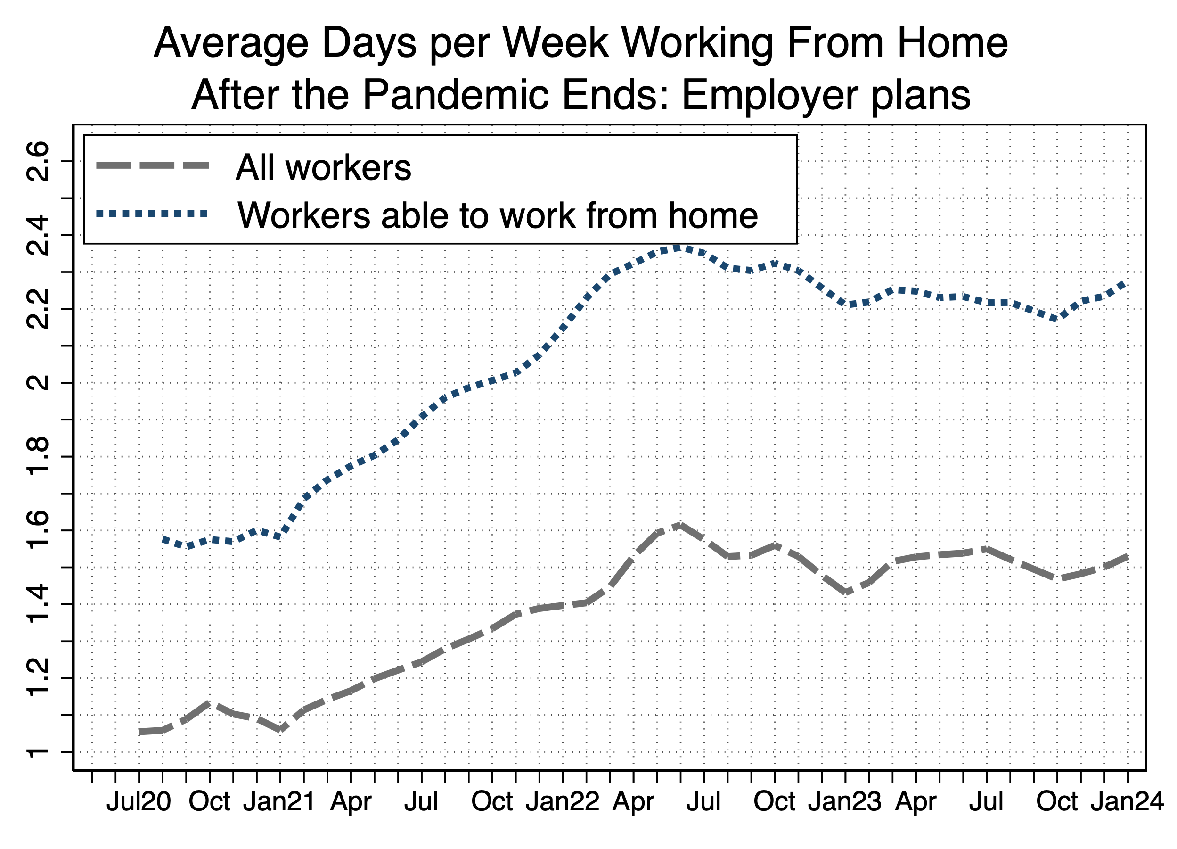

Despite all the talk of businesses forcing workers to return to the office (RTO) full time, the latest data from Stanford’s WFH Research team show that the level of remote work in the United States has remained remarkably steady since 2022 and is poised to stay at these or even higher levels in 2024. In particular, about 30 percent of all paid full work days are now done from home—up from only 5 to 7 percent during the decade before the pandemic—and employers’ plans to utilize remote work over the next year have actually ticked up a bit in recent months:

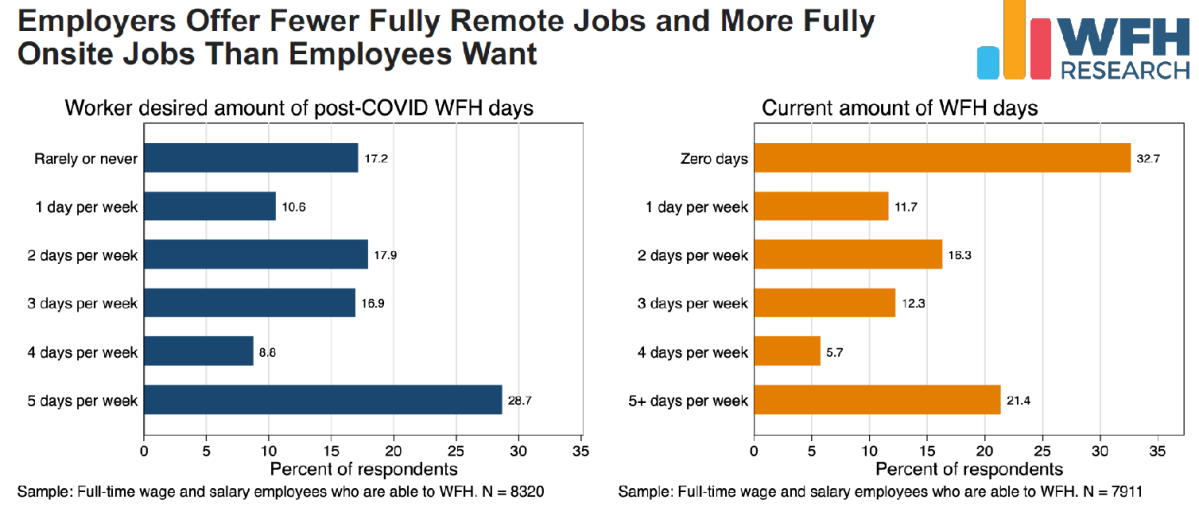

This doesn’t mean that everyone is working remotely all the time. Instead, most workers and employers seem to agree that their preferred setup is a hybrid approach—a few days in the office and a few days out—with each group disagreeing only over the proper balance between the two. As you can see from the following chart, only about 29 percent of workers report that they want to avoid the office altogether:

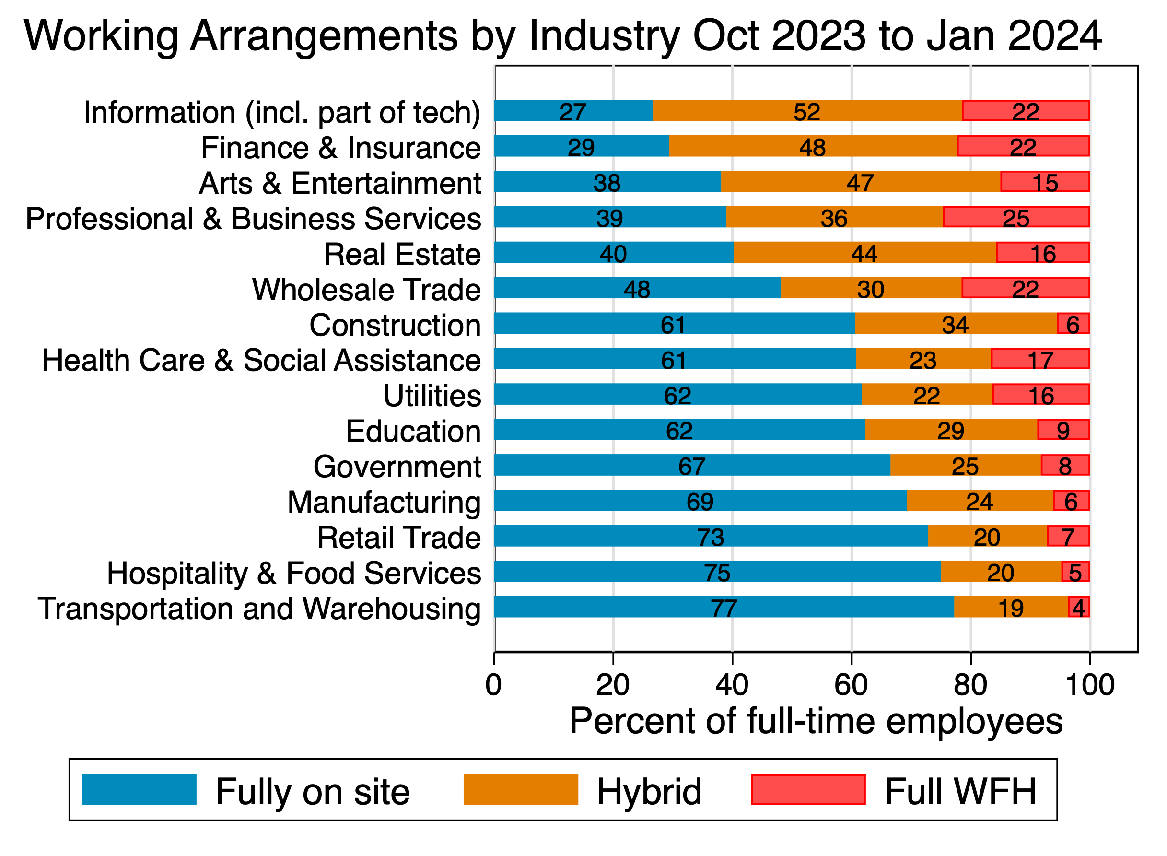

The other big (and unsurprising) differentiator is the industry at issue, with remote work levels varying greatly depending on the type of work typically performed at these establishments. Still, even U.S. industries requiring in-person workers—warehousing, food service, retail, etc.—have at least 20 percent of their employees working remotely some or all of the time:

Remote work’s durability is evident in other countries, too. In the U.K., for example, a new survey of 2,500 U.K. firm managers shows they expect levels of remote work in 2028 to be almost identical to the levels they’re seeing in 2023.

The study’s authors add that the overall level of U.K. remote work in 2028 could rise above these predicted levels because younger firms tend to use remote work more.

As Stanford’s Nick Bloom noted in the New York Times late last year, return-to-office mandates and recession fears are unlikely to change these trends for three reasons. Most obviously, a lot of people really, really like working from home at least some of the time, and see plenty of benefits for doing so:

Second, Bloom notes that the remote work “revolution” wasn’t really all that revolutionary. Instead, firms had been increasing their use of remote work dating back to the 1960s, driven by changes in the types of jobs we do and the technology (personal computers, the internet, Zoom, etc.) available to do it. The pandemic thus accelerated a pre-existing trend rather than creating an entirely new one. That makes the current situation more durable (i.e. less likely to reverse course).

Third, remote work’s durability will be reinforced by so-called “business cohort effects”:

In the data, we see that more than 75 percent of start-ups allow employees flexible working locations. Start-up companies have been born in an era when having an office is optional and meeting customers and clients online is standard. Many of these companies have saved capital by forgoing offices and have saved on expensive urban salaries by hiring remote employees globally.

Today’s new companies have nearly twice as many days worked from home as those founded 20 years ago. As these young companies grow and mature, they will turn into tomorrow’s medium and large companies, bringing their remote-friendly practices with them. Perhaps as important, their founding chief executives will grow into tomorrow’s business leaders. In 10 years, expect to see leading chief executives and entrepreneurs actively embracing hybrid work rather than begging employees to return to the office.

Beyond Bloom’s three reasons, there’s also now limited evidence—so far, at least—that recent RTO mandates have improved firm performance. A new examination of 137 recent RTO decrees at S&P 500 firms found that the affected companies experienced “no significant changes in financial performance or firm values” following a mandate but did see lower employee ratings for job satisfaction, work-life balance, and senior management. This is just one study, and results surely vary by company and industry. But it’s a decent sign that forcing workers back into the office isn’t some sort of panacea.

Remote Work Brings Many Benefits

Remote work’s benefits are also becoming clearer. Most obviously, remote work options mean happier workers—and not simply because we have more employment options (including by foreign companies) or because we’re collectively avoiding annoying co-workers, bad coffee, expensive lunches, dry cleaning bills, or tens of millions of commuting (and personal grooming!) hours per year. Those things are great, obviously, but AEI’s Brent Orrell points to something deeper: our increased desire for flexibility at work.

A recent AEI survey shows that when it comes to making job decisions, flexibility trumps all. A striking 78 percent of American workers say flexibility in their job is “one of the most or a very important” factor in looking for a job. By contrast, just 55 percent say the same about pay. The American workforce is sending a clear message: Flexibility is no longer just a perk; it’s the crown jewel of employment.

Remote work feeds this preference, which is particularly strong for younger workers and women, and which helps explain why many Americans today are willing to trade a higher salary for the option to work from home at least some of the time.

Speaking of women, new research shows why many of them have such a strong preference for remote work: It provides disproportionate benefits to working moms. In a separate blog post, Orrell summarized the new findings well (emphasis his):

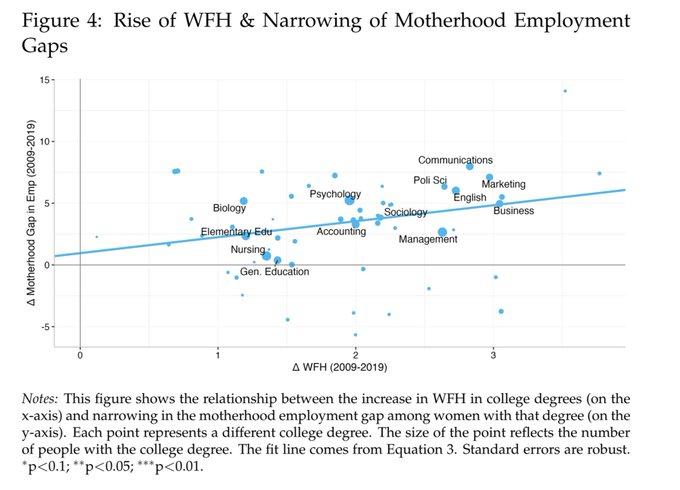

A recent study by Emma Harrington and Matthew E. Kahn delves into the benefits these opportunities can bring for mothers. Using data from US household surveys and time-diaries to assess the prevalence of WFH, they found that in fields where the opportunity to work remotely increased, so too did the employment rates of mothers compared to women without children. Specifically, a 10 percent rise in WFH led to an approximately 0.78 percentage point increase in employment among mothers relative to other women, with significant narrowing of employment gaps in traditionally less family-friendly fields such as finance and marketing. Notably, an analogous effect was not found for men.

Here’s the telling chart:

These results aren’t surprising for anyone with a kid and a remote work option, but they still have important implications for gender equality (reducing the “motherhood penalty” many working moms face), economic growth (increasing the supply of mothers in the workforce and their economic output), and family and child development (making it easier for parents to have kids and spend time with them). I can definitely attest to the last one.

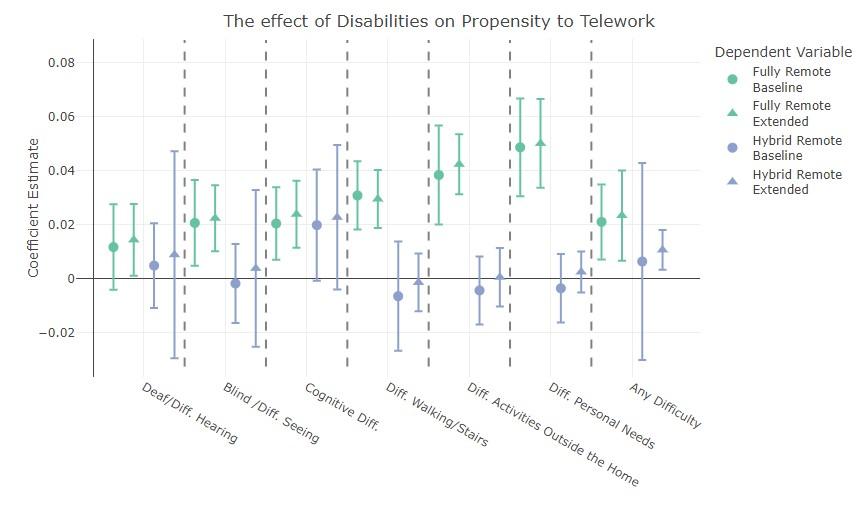

Remote work is also providing new opportunities for disabled workers. According to new research from the Economic Innovation Group, the disabled are substantially more likely to work in a fully remote position, even after controlling for education, occupation, industry, and other individual characteristics. In particular, “a worker who reports any disability is 2.4% more likely to be full-remote than an otherwise similar worker. This represents a 22% increase in likelihood of being full-remote compared to the population-wide average of 10.7%.” Workers with physical or mental health limitations saw even bigger benefits, for perfectly understandable reasons.

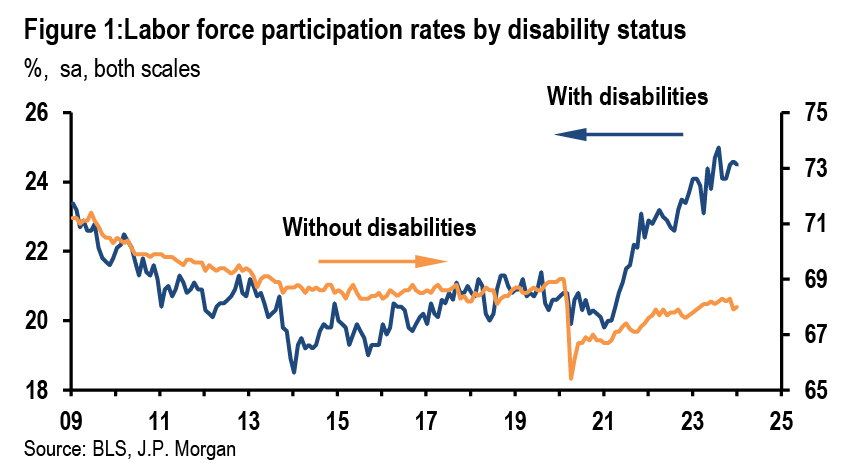

Meanwhile, JPMorgan’s Michael Feroli notes the broader economic impact of this change: “arguably the most welcome economic surprise of the last three years has been the recovery in labor force participation,” and people with disabilities “have been central to this recovery."

Not all of this change in labor force participation can be attributed to remote work—a tight labor market played a role too. Still, much of the rise in disabled workers’ participation in the formal economy is undoubtedly owed to the increasing prevalence of remote work options across the United States.

Finally, there’s little to suggest—as many feared—that remote work would lead to a significant decline in productivity. In the U.K. study above, more remote work is associated with higher productivity, while other research shows small productivity benefits for hybrid work (but small negative ones for fully remote positions). Pre-pandemic studies of specific firms are even more positive. Overall, new research from the San Francisco Federal Reserve finds that, at least so far, “teleworking most likely has neither substantially held back nor boosted productivity growth" in the industries sampled.

Stanford’s Bloom is even more optimistic, ascribing at least some of the recent surge in U.S. productivity to remote work, not at the firm or industry level but at the national one:

Furthermore, even if fully remote working reduces individual productivity, by releasing billions of dollars of office and transportation capital for other parts of the economy to use, it stokes a rise in aggregate productivity. Productivity is about outputs relative to inputs, and although fully remote workers may produce less per hour they use a lot less capital, so their impact on aggregate productivity is likely to be positive.

Separately, Bloom tells the New York Times that remote work will also allow U.S. companies to offshore “tedious” jobs and replace them with more “dynamic” ones here, further fueling domestic productivity gains. (And before you get all mad about that, recall that lots of companies abroad are hiring Americans remotely, too.) Bloom admits that this is all going to take “years” to work out, but the initial signs are positive.

Summing It All Up

Remote work isn’t for everyone, of course, and it does come with potential downsides. Maybe the largest one is for young and/or entry-level workers who might find it more difficult to learn from experienced co-workers, embrace company culture, and get mentored on the job. As we discussed in January, remote work’s proliferation has put commercial real estate—and the banks, cafes, and other firms associated with them—under serious pressure. (That this stress is continuing, however, is another sign of remote work’s durability: Firms aren’t abandoning their expensive leases on a whim. And many cities, it should be noted, are coming out ahead overall.)

But the drawbacks are relatively narrow and surmountable, and—as long as markets remain flexible and dynamic (and dumb tax and regulatory policies don’t get in the way)—there’s little reason to think that firms, workers, and cities won’t adjust to our new work normal. That means some people will work onsite most of the time, others will mainly work from home, while others still do a little of both. Offices, homes, and neighborhoods will change, as will work events and processes. Not everyone will come out ahead, but—with more ability to choose how and where we want to work—most of us will.

And, as is usually the case with increased personal and economic freedom, the country will be better off for it.

Chart(s) of the Week

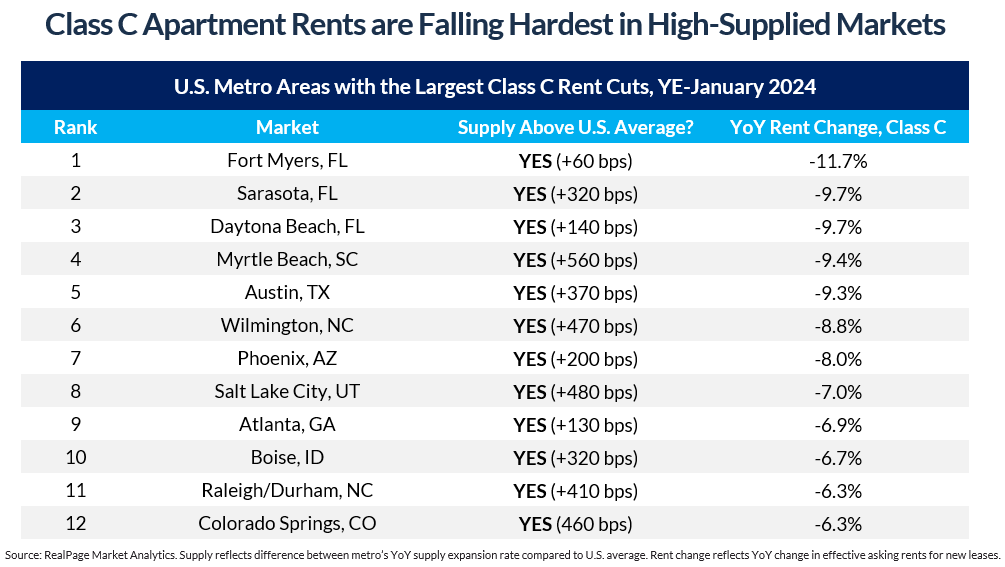

Building market-rate housing lowers low-end rents, too (more)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.