Hey,

So, I’m in Castro’s Back Room in Concord, New Hampshire. I haven’t been here in years, but it looks exactly as I remembered.

Another thing I haven’t done here in a while is rank punditry (I mean here, in this “news”letter). This is in part because I do it in my column and on TV and on podcasts—gotta pay the bills—and in part because we have people who are better at it than me at The Dispatch.

But this is the week between the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary so if not now, when? And since I’ve got to get to a Dispatch event in a few hours, I’m just going to let the punditry flow until I have to stop.

Let’s start with the obvious. Trump won Iowa, bigly. There’s no getting around that. I don’t think anyone is shocked when I say I’m disappointed. Not surprised, just disappointed. I mean, most disappointments in life aren’t surprises. When I lose the lottery, look at the results on a bathroom scale, discover that the forecast for crappy weather was accurate, or wake up to a hangover, it’s often disappointing, but rarely surprising.

One thing you hear a lot is that Monday’s results prove that it’s “Trump’s party” or the “GOP is a MAGA party now.” Obviously, this is not completely or even mostly wrong, but I don’t think it’s entirely right, either. As many of us have been arguing for a long time now, Trump is essentially running as an incumbent. This is very unusual because he’s not an incumbent. Former presidents usually don’t run again. Losing former presidents who run again are even more rare. Grover Cleveland was the only president to lose and run again—and win.

Trump, meanwhile, is the only loser to refuse to admit he lost.

That makes things even more complicated because so many Republican politicians have proved too cowardly to admit he lost. Most of his primary opponents have conceded that Trump lost, but they refused to make a big deal about it when it might have mattered. The GOP and much of the broader right-wing media complex allowed Trump’s lies to take root and grow until they became a kind of litmus test of loyalty or purity on the right. Whether you see that primarily as a collective action problem or widespread cowardice is up to you. But it seems clear to me that the collective action problem fueled the cowardice and the cowardice fueled the collective action problem.

But back to this incumbent thing. One of my frustrations with a lot of the post-mortem Iowa punditry confuses the significance of this incumbency framework. Friends of mine will say he’s got an incumbent’s hold on the party, which is something I’ve been saying for a long time. But then they’ll compare his showing to races where there was no incumbent. In other words, who cares how Trump performed compared to Bush in 2000 or Dole in 1996? The relevant question is how he compares to Bush in 2004 or Reagan in 1984. The answer? Not good. Why? Because actual incumbents usually run unopposed.

If a sitting president actually allowed a caucus and only got 51 percent of the vote, that would be an epochal disaster. Lyndon Johnson opted not to run again in 1968, because Eugene McCarthy came within 7 points of beating him in the New Hampshire primary—and McCarthy was the only challenger on the ballot.

Now, I’m not arguing that Trump’s win is a sign of weakness as a candidate. But if you’re going to call him a de facto incumbent, then by that metric he’s an incredibly weak one.

Still one of the advantages of being an incumbent—virtual or literal—is that your coalition is automatically broader than for a conventional challenger. A lot of the post-Iowa analysis lumps Trump voters into the “MAGA” coalition or Trump base. Here’s Dave Weigel:

Weigel, who is very good at this stuff, obviously has a point. But incumbents usually get support from outside their core constituencies. Reagan put George H.W. Bush on his ticket in 1980 because the Nixon-Ford-Bush wing of the party was skeptical of him. Reagan’s victory in 1980 didn’t mean the entire party was full-tilt Reaganite. George H.W. Bush was unpopular with many factions of the right. But Republicans rallied to the head of their party all the same. The point isn’t that Trump isn’t popular outside his pure MAGA fan base; the point is that talking about different factions is of limited utility when the party is rallying to its figurehead, which is what happens for all incumbents. Talk of “lanes” just doesn’t work the way it normally does (and it’s always been of limited utility). If this were a normal contested race, Trump would be a colossus. But if he were a sitting president, his showing would be a disaster.

The fact of the matter is that Trump is an unprecedented hybrid, a quasi-incumbent who is not a sitting president. Judge him as an incumbent and he’s weak. Judge as a fresh challenger and he’s incredibly strong. Judge him as the hybrid he is and you get a glimpse of why this whole situation is so weird and hard to game out.

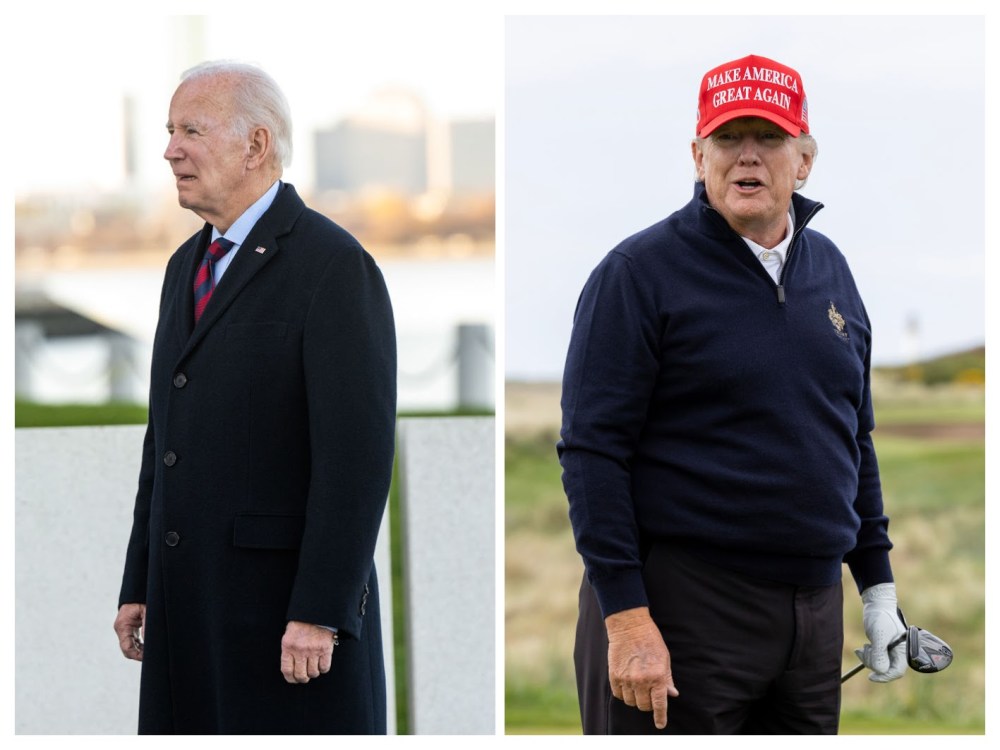

You know who else is an incredibly weak incumbent? Joe Biden.

This is one reason—among many—why the argument about electability isn’t very powerful. If Biden had a 60 percent approval rating or if he fared better in hypothetical matchups against Trump, but not Haley, DeSantis, or a generic Republican, Trump’s weakness would be a much bigger issue. But because of the aforementioned cowardice and collective action problems, the GOP let Trump off the hook. Rather than make him radioactive when that was possible (and, I would argue, morally necessary), the GOP and its enablers rehabilitated him. They rallied to his defense—or stayed quiet—over January 6, over losing the election, over lying about losing the election, on impeachment, and of course his criminal cases.

DeSantis clearly recognizes this, but for all of his recent, accurate, criticism of Trump, Fox News, etc. it’s all too little too late.

So now the primary electorate has a completely understandable belief that Trump can beat Biden—and I think he can. But I think it’s much more unlikely than they do.

Right now, Biden is suffering from all of the problems of a real incumbent while Trump is benefitting from nearly all of the advantages of being an incumbent. I say nearly all because actually being president has real unique advantages—Air Force One, commander in chief, and all that. But many of the advantages of incumbency apply to Trump as well. He has a virtual bully pulpit that is arguably as powerful as the real one. Trump can generate “free media” news coverage in ways no non-sitting president has ever been able to. His plane can do nearly all of the things Air Force One can do. He can command support from right-wing stakeholders, who are all too eager to paint criticism of Trump as Republican disloyalty.

But Trump’s hybrid candidacy also frees him from all of the constraints of actual incumbency. He doesn’t have to do the job of being president. And, because of the idiotic failures of the GOP, the memory of his actual presidency has been gauzed-up to the point where most elected Republican politicians can say with a straight face that the only downsides of his tenure were a few “mean tweets.”

Because of this cultivated nostalgia for his “great” presidency, a lot of Republicans can’t grasp that their memory of his presidency is not how a majority of Americans viewed it at the time. And while many have forgotten the downsides of his presidency, that doesn’t mean they can’t be easily reminded of them. Nor does it mean that people can’t be persuaded that the second term won’t be worse than the first one, which it certainly would be.

And that’s exactly what the Democrats and mainstream media will do. They won’t be subtle. They won’t necessarily even be accurate or fair. But that’s all beside the point. The question is whether they will be persuasive. I’m not asking whether they will persuade many of the 74 million people who voted for Trump last time. But will they be persuasive to a majority of the 7 million more people who voted for Biden? Moreover, contrary to a lot of ridiculous talking points in the wake of January 6, none of the people who voted for Trump in 2020 voted for him to behave the way he did after he lost. The absurd claim, made constantly during Trump’s second impeachment, that impeaching him would be an insult to the 74 million people who voted for him insinuated that all of those people endorsed his attempt to steal the election and rile up the mob. There may not be nearly enough Republicans willing to hold January 6 against him, but it is preposterous to think he added people to his column because of it.

In other words, for Trump to win, he’s got to do better than last time when voters are faced yet again with another “binary choice.” If all you do is listen to right-wing media, you might think that’s exactly what will happen. But that assumes millions of people who voted against Trump—prior to January 6 and prior to all of these indictments (and possibly convictions)—will now vote for him. Maybe that will happen. Or maybe enough people will vote third party, or just not vote at all, to make up the difference. But that’s a hell of a flier to take.

But that’s precisely the flier the GOP is poised to take. They think the mythological Trump, not the real one, is the candidate they’re voting for. In reality, Trump was never a popular president, or even a popular candidate. In 2016 and 2020, he got a smaller share of the popular vote than Mitt Romney did in 2012. Since he ran for office, the GOP has gotten smaller, literally and figuratively. He’s certainly converted more Republicans to Trumpism, but there’s no evidence he’s converted more Americans to it. Trump has done nearly everything he can to make the Trump Party a “rump party” (though in fairness to my inveterate both-sidesism, the Democrats seem determined to do everything can to deny Trump success on this score).

A quarter of Trump supporters oppose having him on the ticket if he’s convicted in his criminal cases. Thirty-one percent of Iowa caucus-goers said he shouldn’t be the nominee if convicted. I think those numbers are on the high side. And he might avoid conviction—not because he’s innocent, but because he’ll succeed in delaying conviction until after the election. But for a guy with a ceiling of roughly 46-48 percent of the electorate, you can trim those numbers by half or even two-thirds and see the chasm in front of a Trump candidacy.

I’m sure, by the way, that many DeSantis and Haley supporters will eventually rally to Trump should he be the nominee. But not all of them will. I’ve really enjoyed hearing from all the Latter-day Never Trumpers in my DMs and inbox. They’ll never use the term, which is fine. But it’s nonetheless enjoyable to see the ranks of anti-Trumpism from the right swell these days.

Right now, it’s easy to see how Biden can lose—and he certainly can. But, because Biden is the actual president, the issues work against him. His coalition has the luxury of griping—about his handling of the war in Gaza, for failing to cancel student loan debt, for not doing enough on the climate. But there’s no reason to believe that has to continue on this path through November. There’s going to come a time when he’ll have the luxury of calling their bluff. Take the overhyped—but real—problem Biden has with Arab-Americans in Michigan. How many ads can Biden run of Trump talking about his Muslim ban and immigrants poisoning American blood before many of them—sorry, enough of them—come home?

Again, I think it’s woefully irresponsible of the Democrats to nominate a guy who could lose to Trump. But it’s also ridiculous for Republicans to nominate a guy who could lose to Biden, particularly a guy who, on the merits, is unfit for office.

But here we are. Barring some wild surprises, we’re almost certainly going to have another election like 2016, in which most Americans don’t want to choose between candidates so unpopular they have a chance to lose to the other.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.