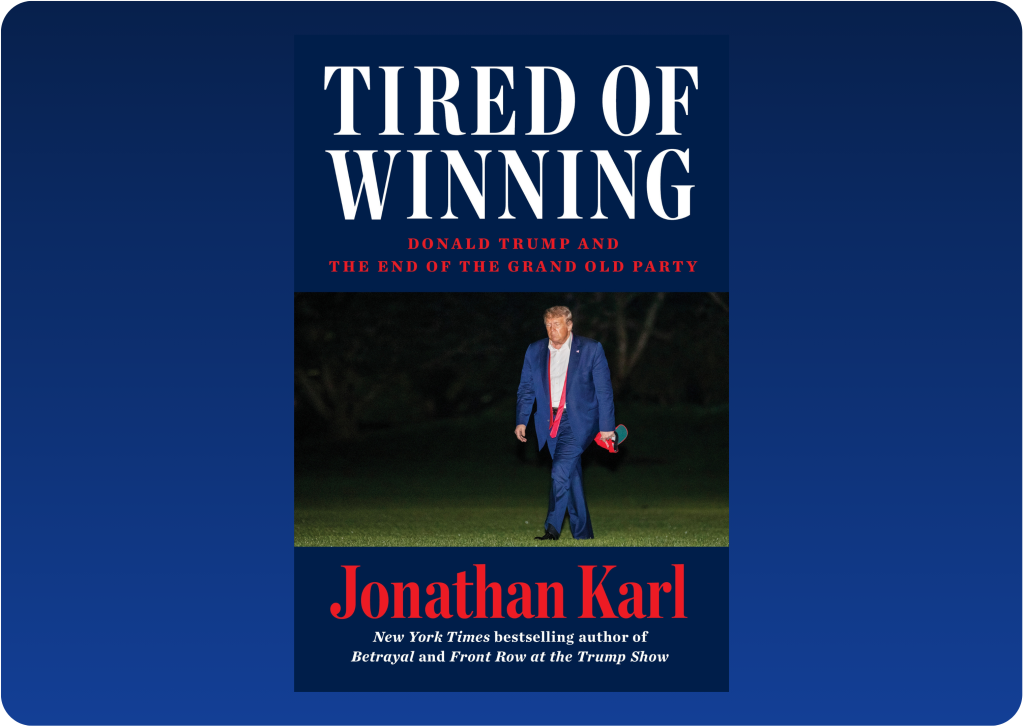

The essay below is adapted from Jonathan Karl’s forthcoming book, Tired of Winning. Disclosure: Declan Garvey, The Dispatch’s executive editor, served as a researcher for the book.

After two years of desperately working to undo the results of the last election—and pursuing preposterous schemes to eject the current president and get back into the White House—Donald Trump looked at the 2022 midterms as the moment he would complete his political comeback the old‐fashioned way: leading his party to victory in a new election. Republican candidates—many of whom were essentially chosen by Trump over the past year—were widely expected to do very well, not only winning back control of both chambers of Congress from Democrats, but also taking back governors’ mansions, secretaries of state offices, and state legislatures across the country. And if they did, Trump—who’d made himself a central figure in the election by issuing hundreds of endorsements and holding rallies in eight states during the campaign’s final month—could plausibly claim to once again be the clear leader of the GOP.

“I think if [Republicans] win, I should get all of the credit,” he told NewsNation as polls opened on November 8, 2022. Almost as an afterthought, he added, “And if they lose, I should not be blamed at all.” By that point, Trump’s hedge seemed unnecessary. The party in power almost always faces a shellacking in the midterm elections, and Democrats—led by an unpopular president in Joe Biden—were considered particularly vulnerable. Voters routinely listed high inflation and rising crime among their biggest concerns and tended to blame Democrats’ policies. When the election analysts over at FiveThirtyEight published the final pre-election update on November 8, they projected a range of possible outcomes that had Republicans winning an average of 230 House seats to the Democrats’ 205—with the potential for the tally to grow even more lopsided.

Republicans themselves were more bullish. At a pre-election National Republican Campaign Committee briefing I attended, the operatives spearheading the party’s efforts to take back the House gave me a list of 74 Democratic seats they believed Republicans had a realistic shot of winning—enough to win not just a majority but the largest Republican majority in more than 100 years. In the Senate, the GOP needed to flip only one seat to take back the majority, and party leaders thought they could pick up as many as four. “I am incredibly optimistic,” Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas told Fox News the day before the elections. “I think this is going to be, not just a red wave, but a red tsunami.”

Things were looking so good for Republicans, in fact, that in the days leading up to the election, Trump’s biggest concern was whether he’d receive sufficient credit for all the victories. To ensure he earned the recognition and gratitude he believed he deserved, the former president cooked up a scheme: He’d announce his 2024 presidential bid before the midterms. Such a move would not only win back the national spotlight he missed so much but allow him to claim the GOP wins as his own.

Essentially everyone in Trump’s orbit thought this was a terrible idea, and GOP leaders hated it even more. Republican operatives had spent hundreds of millions of advertising dollars in recent months hammering Democrats on two things: inflation and crime. Democrats, meanwhile, figured their only hope was to desperately try to brand even the most moderate and traditional Republicans as “ultra MAGA” Trump acolytes. A Trump presidential campaign announcement would play right into their efforts to make the midterm elections a referendum on the deeply unpopular former president instead of the deeply unpopular current president. And as much credit as Trump hoped to snag with his early entry into the race, his advisers worried he’d receive even more blame if he announced and Republicans underperformed.

Trump didn’t care. As Election Day approached, he continually brought up the idea in meetings with his political advisers, who repeatedly reminded him why they believed it was wiser to wait until after the midterms to kick off his 2024 presidential campaign. It became a near‐daily routine: Trump would say he was moving forward with an announcement, and his advisers would talk him out of pulling the trigger. There were, however, still several close calls.

“I ran twice. I won twice—and did much better the second time than I did the first,” Trump falsely told the assembled crowd at an October 22 rally in Robstown, Texas. “And now, in order to make our country successful, safe, and glorious again, I will probably have to do it again.” His fans were ecstatic, erupting immediately into a familiar chant: “USA! USA! USA!”

Almost two weeks later, I traveled to Sioux City, Iowa, for my first Trump event since the 2020 campaign. It was billed as a rally for Iowa Republicans, but as I made my way there, I got an urgent call from a source close to the former president, who told me Trump was now talking about making his 2024 announcement right there in Iowa. Once again, he held back, but only barely. “In order to make our country successful and safe and glorious,” he told the crowd, “I will very, very, very probably do it again.”

“Get ready,” he added. “That’s all I’m telling you. Get ready.”

That was November 3, the Thursday before the midterms. Two days later, I spoke to one of the political operatives Trump had hired for a major role on his expected presidential campaign. He sounded exasperated—and on the verge of quitting. “If he does this, you have to ask yourself, ‘What’s the point?’” the adviser told me after venting about his recurring conversations with Trump. “If he’s not going to listen to any of our advice, why are we here?”

Trump was at it again the day before the election, telling his advisers he wanted to announce his presidential campaign that night in Ohio at a rally he was holding for Senate candidate J.D. Vance. As he boarded his plane in Palm Beach to fly to Dayton for his final midterm rally, Trump’s political team truly didn’t know whether he would go through with it. But once again, he held off. “I’m going to be making a very big announcement on Tuesday, November 15, at Mar‐a‐Lago in Palm Beach, Florida,” he said. “We want nothing to detract from the importance of tomorrow.”

Trump’s advisers may not have wanted him to announce his third presidential campaign before the midterms, but they were confident enough in a “red tsunami” materializing on November 8 that they planned an election night party, inviting supporters, club members, and reporters to Mar‐a‐Lago to watch the results roll in—and to see the former president bask in the glow of a triumphant election night for the first time since 2016. Trump wanted an audience for his re-coronation as the leader of the Republican Party.

As attendees filtered into the main ballroom at Mar‐a‐Lago that Tuesday evening, they were met with magnificent chandeliers and a row of American flags. Enormous television screens had been wheeled into the room so guests could watch Fox News as election updates trickled in, and Trump—joined by high‐level staffers on his campaign‐in‐waiting—sat at a table that was cordoned off by a velvet rope at the front of the room. Next to his table was a stage with a podium, where the former president—and future presidential candidate—would deliver celebratory remarks as results started rolling in.

As the clock struck 7 p.m. and polls began to close along the East Coast, everything seemed to be going according to plan. In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis and Sen. Marco Rubio were quickly projected to win their respective bids for reelection, and Democratic representatives from New York began dropping like flies. “To start the night, Republicans are already +4 in the House—just in Florida,” conservative activist Matt Schlapp tweeted shortly after 8 p.m. “If these trends continue nationwide Democrats are in for a very long night.” Donald Trump Jr. was even more optimistic: “Bloodbath!!!”

But before long, the tide began to turn. Josh Shapiro, the Democratic gubernatorial nominee in Pennsylvania, was projected the winner over Republican Doug Mastriano—the first of several Trump candidates destined to lose in a landslide. As the night wore on, a clear pattern began to develop: Republicans in competitive races who’d shown some independence from Trump were winning, while those who’d tied themselves closely to the former president were losing.

In New Hampshire, for example, Republican Gov. Chris Sununu, a frequent Trump critic, trounced his Democratic opponent, while the GOP’s election‐denying Senate candidate, Don Bolduc, was beaten decisively by Maggie Hassan—arguably the Democrats’ most vulnerable incumbent senator. The difference was astounding: Republican Sununu won by more than 15 percentage points, while Republican Bolduc lost by more than 9. Georgia was playing out the same way. Gov. Brian Kemp—who had often clashed with Trump and refused to go along with his effort to overturn the 2020 election results in his state—easily won reelection against Democrat Stacey Abrams, while Herschel Walker, the former football star Trump had recruited to run for Senate, was trailing Raphael Warnock, another Democratic incumbent Republicans believed would be easy to beat.

For Trump, it would only get worse. Most of the candidates he had endorsed in ruby‐red states and districts were winning as expected, sure, but in the contested races, most of Trump’s candidates were going down. And on top of that, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis—then considered the strongest challenger to Trump for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination—had secured perhaps the most impressive victory of all, despite Trump attacking him as Ron “DeSanctimonious” just days before the election. He defeated Democrat Charlie Crist by 19.4 percentage points after Trump had won Florida by just 3.3 points two years earlier.

Sitting around that table in the Mar‐a‐Lago ballroom with his advisers, Trump knew exactly what was happening. He seemed to want to leave the party, but he also didn’t want to be seen walking out. As one Trump confidant who was with him that night told me, almost no one wanted to be near the former president as he grew more and more agitated: “Boris was the only one who wanted to sit next to him,” the confidant said, referring to Boris Epshteyn—widely viewed as one of Trump’s most sycophantic advisers.

Earlier in the evening, a more confident Trump had told reporters he’d be making remarks after the results came in. When Trump finally went up to the podium, he gave one of the briefest—and most timid—speeches I’ve ever seen him deliver. “Well, thank you very much everybody,” he started off. “This has been a very exciting night. We have some races that are hot and heavy, and we’re all watching them here. And some of you like the music so much that you’d rather hear the music—and I understand that very well.”

All told, he spoke for just over four minutes, trying to spin his colossal failure into a win. But even the Trump‐endorsed candidates who prevailed had underperformed. Ted Budd, Trump’s candidate in North Carolina, won his race by just over 3 percentage points, six years after Richard Burr, the retiring senator he’d be replacing, had won the seat by nearly twice as much. J.D. Vance got a shout‐out for his 6‐point triumph in Ohio, even though Mike DeWine—Ohio’s more traditional Republican governor, whom Trump despised—won by 25 points. Trump highlighted Marco Rubio’s landslide reelection—he’d held a rally with the Florida senator days earlier—but neglected to mention DeSantis had won by even more. “We have a lot of big races going on right now, so enjoy that,” Trump concluded. “Enjoy the food and enjoy everything.”

After thanking the crowd one more time, he gave attendees a half‐hearted fist pump and walked off the stage and directly out of the ballroom, not to be seen again that night. “For those many people that are being fed the fake narrative from the corrupt media that I am Angry about the Midterms, don’t believe it,” he’d later post on Truth Social. “I am not at all angry.”

For some Republicans, November 8, 2022, managed to do what January 6, 2021, did not: wake them up to the dangers of sticking with Trump, and give them the courage to speak out against him. “The voters have spoken and they have said that they want a different leader,” Virginia’s GOP Lt. Gov. Winsome Earle‐Sears, who in 2020 had served as co-chair of a group called Black Americans to Re‐Elect the President, told Neil Cavuto on Fox Business. “And a true leader understands when they have become a liability.”

In January 2021, former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan had condemned Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election on moral and constitutional grounds, arguing it was “difficult to conceive of a more anti‐democratic and anti‐conservative act.” After the awful Republican performance in the 2022 midterms, Ryan appealed to his fellow Republicans’ instinct for political survival.

“With Trump, we lose,” he told me shortly after the midterms. “It’s just evidence. We lost the House in ’18. We lost the presidency in ’20. We lost the Senate in ’20. And now, in 2022, we should have—and could have—won the Senate. We didn’t. And we have a much lower majority in the House because of that Trump factor.”

It took several days for all the votes to be tallied—particularly in Arizona, Nevada, and California—but Ryan was right: Republicans underperformed not only their own outsize expectations but also decades of historical midterm trends. Those 74 Democratic House seats they believed they had a chance to flip? They lost 64 of them. And in the Senate, the GOP needed to pick up only one Democratic seat to retake the majority and bring Biden’s agenda to a screeching halt. They lost every single one of them. In fact, Democrats increased their majority by winning retiring Republican Pat Toomey’s Senate seat in Pennsylvania.

“I think my party needs to face the fact that if fealty to Donald Trump is the primary criteria for selecting candidates, we’re probably not going to do really well,” Toomey told CNN’s Erin Burnett on November 10. “All over the country, there’s a very high correlation between MAGA candidates and big losses—or at least dramatically underperforming.” Republicans being honest with themselves were immediately able to identify what went wrong.

When I interviewed Donald Trump in March 2021, he had been eager to prove his influence in the upcoming primaries. “If you got a Ronald Reagan endorsement, it meant nothing other than it was a nice thing to have,” he told me. “[But] people have gone up 20, 30 points [with my endorsement]. People will not get elected without the endorsement. And I don’t say that in a bragging tone. I’m just looking at the numbers.”

“I would not dispute that you are the single most influential voice in the Republican—”

He cut me off before I could finish the sentence: “In history. In history.”

As hyperbolic as that sounded, Trump was probably right. Less than three months after he left office with a 29 percent approval rating—the lowest of his presidency—Republicans were banging down the door at Mar‐a‐Lago, vying for his support. By the time I sat down with him on March 18, 2021, he’d already offered his “Complete & Total Endorsement” to several GOP senators up for reelection in 2022, as well as to former White House staffers Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who was running for governor in Arkansas, and Max Miller, who was mounting a primary challenge to Rep. Anthony Gonzalez in Ohio.

“This is like Grand Central Station,” Trump said, ticking through all the candidates who’d made the pilgrimage to Mar‐a‐Lago seeking his backing. “[I’ve got] many coming. People that you wouldn’t even believe, because there’s never been an endorsement like it.”

One such candidate who would travel to Palm Beach was David McCormick, a Gulf War veteran and highly successful hedge fund executive who’d held multiple senior roles in the George W. Bush administration. He was born and raised in Pennsylvania, and his wife, Dina Powell, had served as Trump’s deputy national security adviser. Between McCormick’s military record, deep ties to the state of Pennsylvania, government experience, and ability to finance his own campaign, Republican strategists viewed him as the perfect candidate to succeed retiring GOP Sen. Pat Toomey.

McCormick brought on several Trumpworld alums to advise his campaign—including Trump’s former policy adviser and speechwriter Stephen Miller and former spokesperson Hope Hicks. To win the Republican nomination, McCormick figured he would at least need to be on good terms with the former president. And in December 2021, McCormick made the journey to Mar‐a‐Lago to personally let Trump know he’d be jumping into the race a few weeks later. He didn’t expect an endorsement from the former president, but he didn’t think he needed it, either. McCormick figured that as long as Trump stayed neutral, he would be in a good position to secure the nomination.

But the aspiring senator’s second Mar‐a‐Lago visit, in early April 2022, didn’t go as well as his first. After the two men exchanged pleasantries, Trump invited McCormick—along with Powell and Hicks—up to his office. As Trump sat behind his desk—which was designed to look like the one he’d used in the Oval Office, sort of like a fake Resolute Desk—he called out to his secretary, Molly Michael.

“Molly, show them the video,” Trump said, according to two people who attended the meeting.

And with that, Trump’s personal secretary played the group a clip of a little‐seen and long‐forgotten Bloomberg News TV interview McCormick had done in January 2021—shortly after the attack on the Capitol—in his capacity as CEO of the hedge fund Bridgewater Associates.

“I think what we have to not embrace is the divisiveness that’s characterized the last four years and the polarization,” McCormick told Bloomberg anchor Erik Schatzker when asked whether the Republican Party should move on from Trumpism. “I think the president has some responsibility—a lot of responsibility—for that.”

When the video clip ended, Trump turned back to McCormick. “That’s very bad,” he told him. “Why would you say bad things about me?”

In reality, McCormick did not say anything in that old interview that Republican leaders in Congress hadn’t said in the days after January 6, when even Kevin McCarthy had argued—on the House floor, not in some obscure interview—that Trump bore responsibility for what happened. As long as Republicans like McCarthy came back into the fold, Trump had shown a willingness to forgive them. “I think it’s all a big compliment, frankly,” he told the Wall Street Journal about those who had once criticized him. “They realized they were wrong and supported me.”

McCormick had stopped saying anything negative about Trump well before that April meeting and had even reversed himself in an interview on the podcast PoliticsPA after that first visit to Mar‐a‐ Lago, saying he didn’t think Trump should be held accountable for January 6. But it wasn’t enough. Trump needed him to prove his loyalty—and to pay a price for what he’d said on Bloomberg more than a year earlier. But it was a price McCormick wasn’t willing to pay.

“I know Pennsylvania,” Trump said after they watched the video clip. “You cannot win unless you say the election was stolen.”

“Mr. President,” McCormick said, “I cannot do that.” He said he agreed there had been some issues with the way the election had played out in Pennsylvania but that it didn’t amount to enough to change the election results.

A few days later, Trump issued an endorsement of McCormick’s opponent, “the brilliant and well‐known Dr. Mehmet Oz.” Like McCormick, Oz also hadn’t echoed Trump’s 2020 election claims. But unlike McCormick, Oz had never publicly criticized the former president, and more importantly, he was a fellow TV star. “I have known Dr. Oz for many years, as have many others, even if only through his very successful television show,” Trump said in making the endorsement. “He has lived with us through the screen and has always been popular, respected, and smart.”

McCormick’s campaign team wasn’t thrilled with the development, but they didn’t see it as the end of the race. Nearly a month later, in fact, their internal polling still showed McCormick with a narrow lead. But that lead evaporated after Trump held a rally for Oz in Pennsylvania less than two weeks before the primary and levied a series of personal attacks against the guy who had come to see him twice at Mar‐a‐Lago. “He did want my endorsement very badly, but I just couldn’t do it,” Trump told the crowd, who had come out to the Westmoreland Fairgrounds in western Pennsylvania despite a rainstorm. “He was with a company that managed money for communist China, and he is absolutely the candidate of special interests and globalists and the Washington establishment.”

Oz thought the attack was so brutally effective that he used it as a television ad that ran right up until the election.

McCormick held up remarkably well despite the onslaught from Trump, but Oz eked out the win by fewer than 1,000 votes—31.21 percent to 31.14 percent. The race was close enough that there’s little doubt Trump’s endorsement made the difference—but it was barely a win, and the former president’s powers did not extend to Oz’s general election against John Fetterman, which Oz lost by about 5 percentage points. With a progressive record as Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor, Fetterman was clearly beatable. And shortly after the primary, he suffered a stroke that kept him off the campaign trail for most of the race. But Oz’s mixed record on social issues rankled some conservative voters, and Fetterman’s team routinely mocked Oz as an out‐of‐touch TV doctor with scant ties to the state.

McCormick might or might not have won the general election, but he was clearly the more electable candidate—and the one Democrats feared more. A few months after his primary loss, McCormick ran into Sen. Chuck Schumer at a party on Long Island, and the Democratic leader told him, “Trump’s an idiot. You would’ve won.” It was flattery, but Schumer was probably right.

But to those who went through the Mar‐a‐Lago circuit in 2022, that didn’t seem to be the former president’s top priority. “I don’t think he gave a s— at all whether we won the Senate,” one Republican Senate candidate told me. “It was all about, ‘Who has the most allegiance to me?’ It was all who was going to be beholden to him.”

The election results for Trump’s candidates were part of a larger pattern: Several post-election studies quantified just how much the Trump factor had hurt Republican candidates. An April 2023 study by the nonpartisan group States United Action, for example, found candidates for state offices overseeing voting who backed Trump’s 2020 election lies in 2022 performed 2.3 to 3.7 percentage points worse than otherwise expected. “Voters rejected candidates specifically because those candidates refused to support free and fair elections,” the report read, noting that “voters who otherwise would have voted for the Republican candidate instead voted for the Democrat” when the Republican repeated Trump’s claims that the 2020 election was stolen.

A study from Nate Cohn at the New York Times further quantified the damage inflicted by the former president in November. Using the Cook Political Report’s primary scoreboard—which sorted GOP nominees into “MAGA” Republicans and “traditional” Republicans—he showed that the MAGA group performed, on average, about 5 percentage points worse than the party’s traditional candidates.

An even deeper dive into the numbers by Philip Wallach, a senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, arrived at a similar conclusion. In the 114 most competitive general election races of 2022, according to his analysis, Republicans backed by Trump underperformed their districts’ historic trend lines by 5 percentage points, while Republicans without Trump’s endorsement outperformed those trend lines by 2.2 percentage points, suggesting Trump himself stopped the red tsunami. “Trump remains quite popular among Republican voters, and his endorsement was decisive in plenty of House primaries this summer,” Wallach wrote. “But close association with the twice‐impeached president was a clear liability in competitive 2022 House races, turning what would have been a modest‐but‐solid Republican majority into (at best) a razor‐thin one.”

Not long after the midterms were over, the Republican National Committee decided to conduct its own after‐action report to analyze the party’s poor performance with an eye toward avoiding similar mistakes in the next election. A draft that began circulating among RNC members in April 2023 accounted for several factors that may have hurt Republican candidates: The Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade, a longtime Republican goal, effectively put abortion rights on the ballot for the first time in decades. Lackluster GOP fundraising had allowed Democrats to dominate the airwaves. Republican voters’ aversion to early and mail‐in voting made it difficult for campaigns to bank votes and determine where to focus their resources on Election Day.The RNC draft report also said the results showed voters are not interested in “relitigating” previous elections. “The Republican candidates in 2022 who delivered results and had a vision for the future did much, much better than those stuck in the past and rehashing old grievances,” the report noted. There was really only one reason the Republican Party had been saddled with so many losing candidates intent on wallowing in those past grievances and relitigating the last election. But there were two words that didn’t appear anywhere in the report: “Donald Trump.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.