“Whatever it is, it’s not working …”

So goes the hermetically sealed logical loop of horse race political punditry.

In the past month, we’ve seen two polls on the Republican presidential nomination worth looking at from Iowa, zero from New Hampshire and one from South Carolina. There are more national polls, but even there, we’re only really talking about six or eight.

And yet … coverage decisions and election narratives live and die based on miniscule changes in infrequently available data. What’s working or not working for campaigns would be hard to determine even in a perfect world of opinion polling, and that is certainly not the world in which we live.

This is not me saying the polls are meaningless, or even that they’re inaccurate. Sure, there’s a lot of garbage polling out there, but there are plenty of good ones, too. I know. I look at all of them and dive deep into their cross tabs and methodologies. I look at the standard deviations so you don’t have to.

But this is me saying that polls can measure only what has happened, not predict the future. We can know, for example, that former President Donald Trump is crushing the competition. We can also feel very confident that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is heading to the bottom like a manatee after a seagrass binge.

But after that, what else could we reliably know? Vivek Ramamswamy seems to have had a moment, picking up 5 points or so nationally since the start of the summer, but now seems … stalled. And the rest of the contenders? Former Vice President Mike Pence, former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, and former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie are all polling about the same. There’s no sense in pretending we can discern something meaningful about the future in the difference between 2 percent and 5 percent. But that won’t stop the political press from trying.

Like a submarine with a broken sonar system, media outlets are bumping around deep underwater looking for the faintest ping on their screens to tell them where to go. Without enough resources to cover the race from the voters’ perspective or enough courage to cover what reporters themselves think might be actually interesting or different, they spin their propellers in search of nonexistent data.

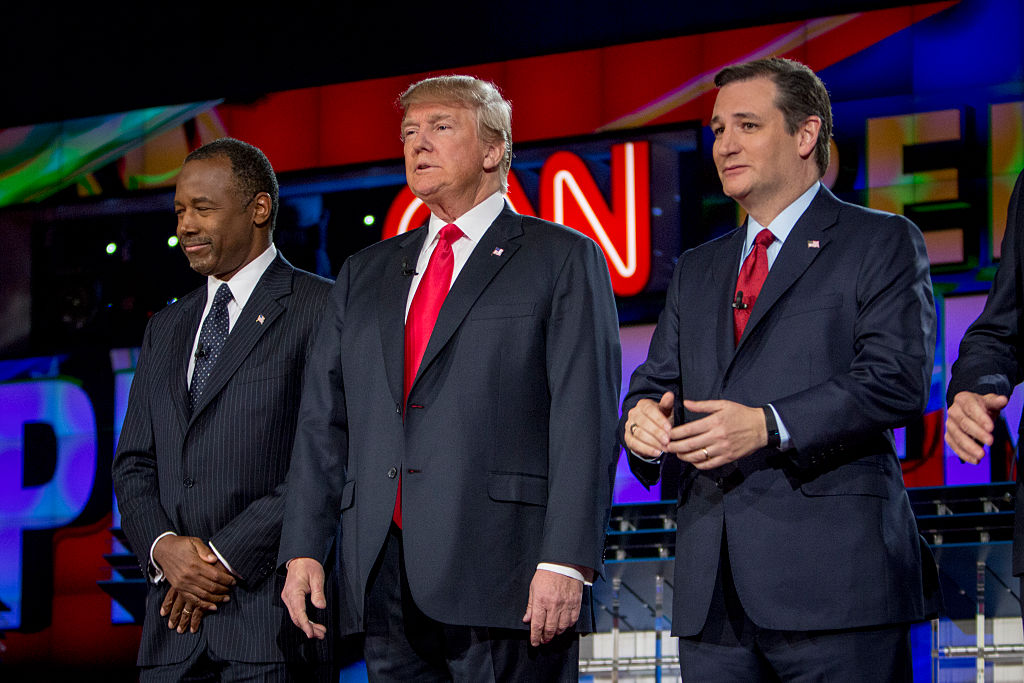

We’re 118 days from the Iowa caucuses. At the same point in the 2016 cycle, similarly scanty Iowa polls showed the eventual winner, Sen. Ted Cruz, in fourth place. The polls showed Trump, Ben Carson, and Carly Fiorina at the top of the heap. They finished second, fourth, and seventh, respectively.

Polls at this point in New Hampshire were more predictive, in that they had Trump, the eventual winner, ahead. But neither of the other top-three performers in the polls, Fiorina and Carson, finished better than sixth. The New Hampshire runner-up that year, then-Ohio Gov. John Kasich, was running a distant fifth. South Carolina was similar. Trump, the eventual winner, was out front, but none of the rest of the top five candidates at this point ended up where polls had them.

George Will tells us that “history is made by intense, compact minorities.” And brother, is the American primary election system proof of that.

Trump was able to win the presidency and shift the direction of American and world history because he managed to get the support of a little less than 32 percent of Republicans in the nominating contests of Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina.

Because of 387,046 people—a population about the size of the city of Aurora, Colorado—Trump went into the decisive March primaries at a gallop. We might be able to get a small sense of what a group that small is thinking right now, but certainly not what they will be thinking 17 weeks from now. They don’t know what they’ll be thinking then either.

Calvin Coolidge is the author of what I think is the best ever quote on the subject, so I repeat it often: “There is only one form of political strategy in which I have any confidence, and that is to try to do the right thing and sometimes to succeed.”

Polling is far more useful in explaining why something happened than predicting what will happen. Demographic data can be marvelously useful in helping campaigns decide how and where to direct their message. But neither polls nor demography can really tell candidates or journalists what will end up working. If Trump has proven anything in his political career, surely that is true.

A guy with no campaign to speak of and who started his campaign well behind the likes of a Mike Huckabee retread and Sen. Rand Paul became the Republican nominee. Polling and demographic data helped us understand how that happened, but not predict that it would. Just look at how DeSantis has foundered trying to follow the numbers. It doesn’t work.

There probably isn’t a path forward for any of the candidates other than Trump in the race as currently constituted. And yet, one of them might win. The upside of being a long shot is supposed to be that you can run like you don’t have anything to lose. The politicians and the press covering them would do well to remember that.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.