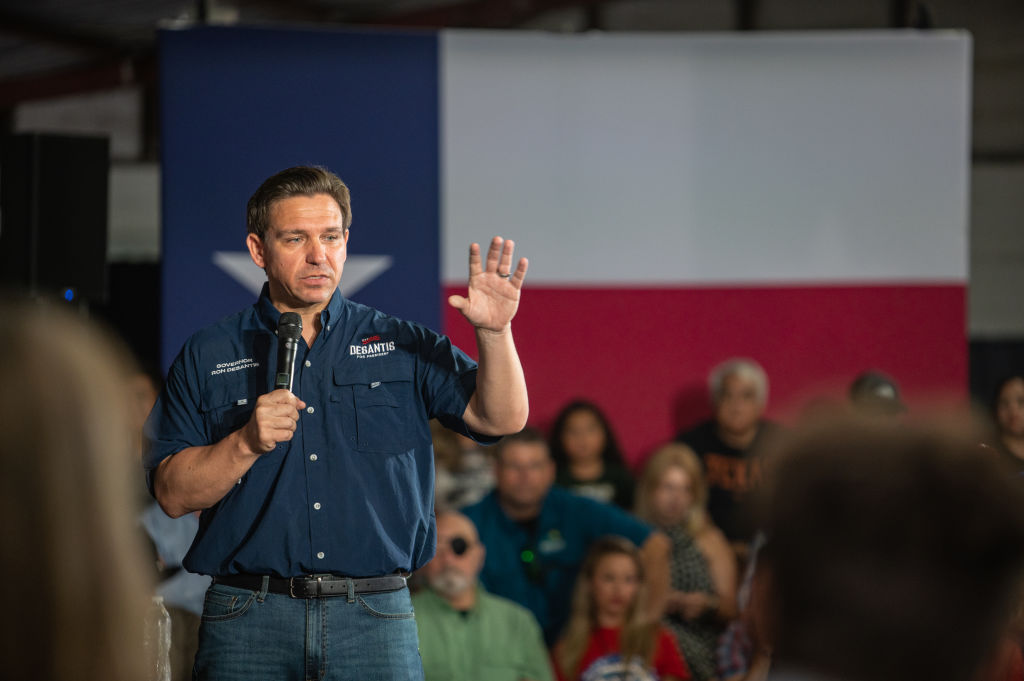

During a visit to the Texas border last week, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced he would take action to eliminate birthright citizenship for American-born children of illegal aliens if elected president next year. Former President Donald Trump has promised the same and teased the idea multiple times during his presidency, though he never followed through.

Nearly everyone born on American soil is automatically a United States citizen, which makes the U.S. an outlier in the world. Only 33 countries offer unrestricted birthright citizenship, almost all of them located in North and South America.

Why does birthright citizenship exist in the U.S., and how is it protected? Would getting rid of it require a constitutional amendment?

The 14th Amendment.

Birthright citizenship is guaranteed in the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment, which was ratified in 1868 and grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the U.S., and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The primary purpose of the clause was to overturn the Supreme Court’s infamous 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, which held that the African American descendants of slaves, even those living in free states, could not be recognized as U.S. citizens. The amendment’s ratification—three years after the Civil War ended—meant that black Americans could finally enjoy official citizenship.

But the citizenship clause doesn’t provide for everyone born in the U.S. The second part of the clause states that in order to be an American citizen, one must also be subject to its jurisdiction—that is, bound by the authority of U.S. law. It’s that provision’s ambiguity that has caused most of the conflict around it: Who falls under America’s jurisdiction, and which groups are left out?

DeSantis claims including children of illegal aliens in this category was “not the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.” At the time of the amendment’s ratification, there were no federal laws restricting immigration to the U.S., so the writers likely intended neither to intentionally grant citizenship to the children of unlawful residents nor explicitly to withhold it. Their main purpose in including the jurisdiction exception was to exclude Native American tribes (which were governed internally) and the children of foreign diplomats.

In the following decades, the question of who exactly was subject to U.S. jurisdiction would be central to the controversy over birthright citizenship.

The precedent.

The Supreme Court offered an answer in the 1873 Slaughterhouse Cases, which held that the “privileges and immunities” protected under the 14th Amendment were limited to the rights of federal citizenship, not state citizenship. According to the court, the groups not subject to U.S. jurisdiction included “children of ministers, consuls, and citizens and subjects of foreign States born within the United States.”

Illegal aliens would certainly not qualify. But the Supreme Court rejected the definition in the 1898 case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, when it ruled that the American-born child of Chinese citizens, who were lawful permanent residents of the U.S., was entitled to American citizenship under the 14th Amendment. Justice Horace Gray, writing for the majority, recalled the original purpose of the citizenship clause had been to extend African Americans equal rights to citizenship, not to further restrict the rights of others.

“[T]he Fourteenth Amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens,” Gray wrote.

Today, the ruling is generally accepted as precedent when considering the status of children of illegal aliens under the citizenship clause. Some, however, argue that the case is irrelevant because Wong Kim Ark’s parents were lawful residents of the U.S.

The debates.

Those who oppose birthright citizenship have alternative interpretations of the citizenship clause that exclude the children of illegal aliens from U.S. jurisdiction. In 1866 Sen. Lyman Trumbull, an advocate of the citizenship clause, defined “subject to U.S. jurisdiction” as “not owing allegiance to anyone else”—a standard which almost all illegal immigrants would fail to meet. More recently, politicians have introduced legislation—such as the Birthright Citizenship Act of 2015 and of 2021—attempting to redefine the meaning of “subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S., explicitly excluding the children of illegal aliens.

Beyond the constitutional questions, politicians have criticized the practice for its role in incentivizing illegal immigration. In a practice known as “birth tourism,” mothers travel to the U.S. for the sole purpose of giving birth to an American citizen, making the path to eventual citizenship easier for themselves in the process. In 2016, 250,000 babies were born to illegal aliens in the U.S., according to Pew Research Center.

Most attempts by lawmakers to push back have been through legislation that offers a narrower interpretation of the citizenship clause rather than proposed amendments to the Constitution. None of the proposed bills have passed yet, but if they do, they likely will be struck down in court, according to most legal scholars. Trump has promised to ban birthright citizenship via executive order, insisting he doesn’t need a constitutional amendment—a claim experts have disputed.

Amending the Constitution, which requires the support of three-quarters of the states, would be next to impossible: 60 percent of Americans support the status quo, according to an Economist and YouGov poll. Eliminating birthright citizenship would “never withstand judicial scrutiny,” Keith Wittington, politics professor at Princeton University, said. “Birthright citizenship is embedded in both clear Supreme Court interpretation of the text and original meaning of the 14th Amendment.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.