Memento mori—commonly translated as “remember you must die”—is a phrase ingrained in popular culture. For Depeche Mode, death has been a companion for more than four decades. In the 1980s, as the band built a following and developed its identity, it steadily embraced a sound preoccupied with darkness and the macabre. “I think that God’s got a sick sense of humor, and when I die, I expect to find Him laughing,” frontman Dave Gahan sang in his typically vibrant baritone on 1984’s “Blasphemous Rumors.” “Death is everywhere,” he’d proclaim the next year, reminding listeners that, like “flies on the windscreen,” they could easily be torn apart.

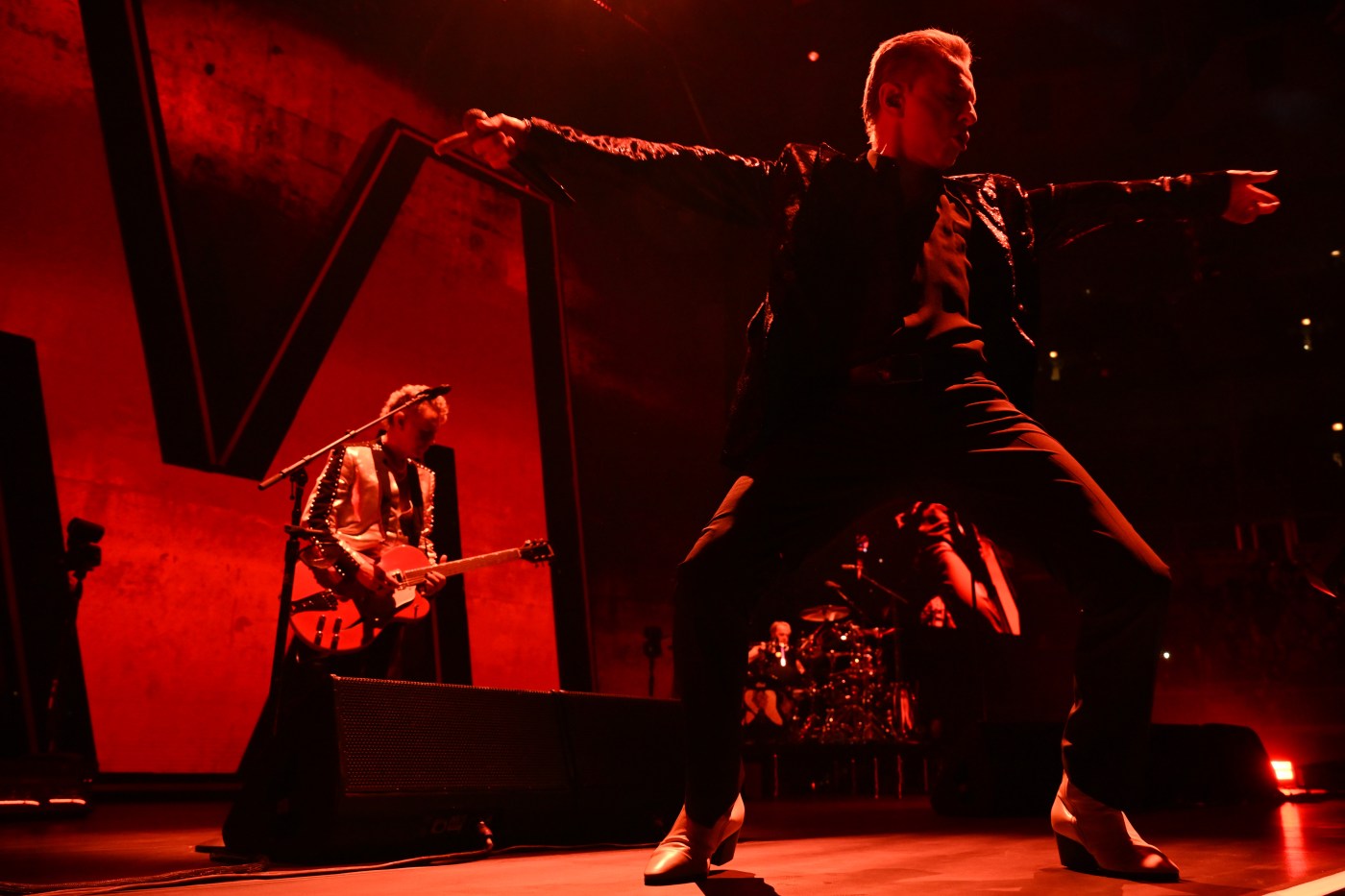

But the group has never been more concerned with mortality than at present. Last year, founding keyboardist Andy Fletcher died suddenly, leaving Gahan and lead songwriter Martin Gore as the only remaining original members. Rather than retiring, they channeled their grief into art, composing a new album permeated by themes of impermanence and loss. The result, Memento Mori, is perhaps Depeche Mode’s coldest release to date; a sparse and sorrowful portrait of a band in mourning, replete with musical allusions to past albums and lyrical references to global crises and personal struggles alike. While the album is an emotional work, it’s also a stiff and monotonous slog, sorely deprived of memorable melodies and compelling hooks.

Since Exciter (2001), Depeche Mode albums have largely offered the same—a few outstanding tracks surrounded by forgettable fluff. Unfortunately, Memento Mori does little to deviate from this disagreeable template. The songs merge together in a middling haze, showing signs of inspiration only sporadically. Granted, the album does possess a few consistently strong qualities. Gahan’s vocals sound richer and more dynamic here than they have in more than a decade, as if his voice has been restored to the soulful peak it reached in the mid-‘90s. There’s a captivating power to all of his performances, whether he’s affecting a wistful croon or an operatic bellow. On “Never Let Me Go,” he growls with primordial intensity, while on “Ghosts Again,” his delicate trills accentuate the song’s melancholic tone. “Time is fleeting, see what it brings,” he warbles. “We know we’ll be ghosts again.”

James Ford’s production is also a highlight. The mix is mercifully free of compression, and there’s a noticeable amount of empty space between the instruments that adds to the somber atmosphere in a manner that evokes Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures. Every synthesizer, tape loop, and drum track is captured with perfect clarity, and even the simpler compositions are marked by a full, lush sound. “Wagging Tongue” is a prominent example. Driven by a straightforward synth line, with lyrics that follow the rhyme scheme of a children’s book, it recalls the playful simplicity of the band’s earliest material on Speak and Spell (1981) and A Broken Frame (1982), while other songs are redolent of the long-haired, grunge-rock-goes-goth style of Songs of Faith and Devotion (1993) and Ultra (1997). Gahan and Gore seem to be summing up their discography: more than an elegy to Fletcher, Memento Mori is a reflection on the artistic legacy of Depeche Mode as an entity. But nostalgic gestures and impressive sonics can’t distract from a lack of boldness in the songwriting, or the blandness that pervades much of the album.

Memento Mori begins with the industrial assault of “My Cosmos Is Mine,” which blends thumping drums with keyboard pulses, grime-coated bass throbs, and scratchy electronic distortions. It’s reasonably intriguing at first, but ultimately, these instrumental flourishes amount to little. The lyrics are slight, and there’s barely anything in the way of an engaging hook, a problem that equally applies to other early songs such as “My Favorite Stranger” and “Don’t Say You Love Me.” Even on “Ghosts Again,” the album’s lead single, things progress with a plod. Though pleasant, it feels overly restrained, as though it’s building up to a grand, emotive swirl of a chorus that never arrives.

Signs of life appear toward the middle of the album, when Gahan and Gore dare to be more inventive in their approach. The Gore-sung “Soul With Me” is an astonishing piece of music; a tender, affecting ballad with a heady chorus that’s at once retro and contemporary. Like Gahan, Gore sings with the resonance and feeling of a man half his age. His lyrics are at their most vivid as he describes a dying person’s entry to the afterlife, and there’s an irresistible beauty to the imagery he creates—“I’m ready for the final pages, kiss goodbye to all my earthly cages, I’m climbing up the golden stairs.” “Never Let Me Go” has a similar vitality; its fuzzy guitar wranglings, boppy bassline, and dramatic bridge provide some overdue excitement. And “People Are Good” offers some crisply cynical lyrics—“Keep fooling myself, that everyone cares, and they’re all full of love”—backed by rumbling, abrasive drums and measured, Kraftwerkian synth stabs. On “Caroline’s Monkey,” Gahan thickens his native accent to tell a familiar, bluntly metaphorical tale of drug addiction. It’s the album’s most bizarre offering; an experiment for its own sake that doesn’t necessarily go anywhere. But compared to the many less distinguishable songs, it’s a refreshing diversion.

Too much of the album, though, is plagued by a hollowness that’s incongruous with the weight of its subject matter. Despite the serious themes at hand, the lyrics are often frustratingly devoid of anything stimulating or meaningful. “Before We Drown” is desperately dull—“I feel so naked, standing on the shore, nothing’s out there, nothing else no more,” Gahan sings mournfully, his quivering voice unable to make the vague words even remotely interesting—and it’s not alone in providing all the substance of a discarded B-side. “Always You” and “Don’t Say You Love Me” are similarly labored, with romantic metaphors so clumsy that “People Are People” sounds comparatively nuanced—“You’ll be the killer, I’ll be the corpse, you’ll be the thriller, and I’ll be the drama, of course.”

Throughout, there’s a baffling absence of hummable tunes or infectious choruses; Gahan and Gore have instead chosen to embrace discordant sounds and gloomy atmospherics. But the emphasis on mood over melody is simply tedious, and it leaves little to connect with in most of the individual tracks. When Memento Mori concludes, its themes linger in the mind, but the actual songs have left only a faint impression. Most of them sound so indistinct that the album unfolds in a kind of numbing blur, and consequently, it seems pointless. In the past, Depeche Mode addressed challenging subjects and raw emotions without abandoning their pop priors—songs as far removed as “Home” and “Everything Counts” managed to simultaneously provide soaring, danceable hooks, and to probe grim topics through thought-provoking lyrics. As with the band’s most recent releases, Memento Mori only occasionally rises to comparable heights; more often than that, it falls far short. Andy Fletcher deserved a farewell, and taken as a tribute, it can certainly be moving. But removed from context, the songs are so tepid that there’s little significance to the album as a whole.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.