French President Charles de Gaulle reportedly sniffed at first sight of a transistor radio, a gift from the prime minister of Japan in 1962.

Today, European policymakers are taking semiconductors much more seriously.

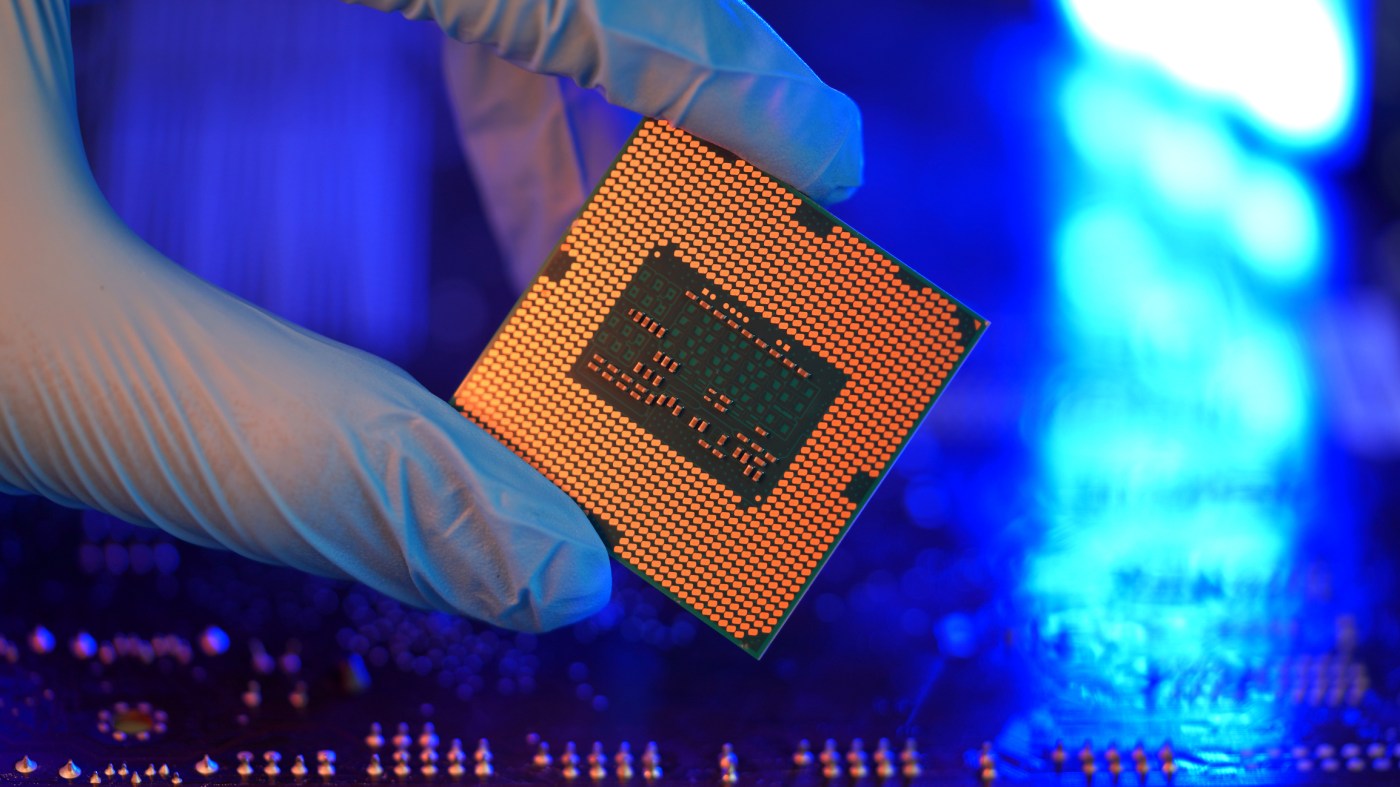

The European Chips Act, proposed by the European Commission in February 2022 and still being negotiated, aims to double semiconductor production within the European Union by 2030, bringing about “a thriving semiconductor sector from research to production and a resilient supply chain.” It promises 43 billion euros in state subsidies—on par with the $53 billion allotted for U.S. production by the CHIPS Act, which President Joe Biden signed into law last August—and a data-gathering program to allow member states to monitor and address shortages.

But some experts are skeptical about what the proposed legislation can really achieve.

“I don't think that the EU Chips Act will fundamentally change Europe's position in the semiconductor value chain,” Jan-Peter Kleinhans, director of technology and geopolitics at Stiftung Neue Verantwortung, a think tank in Berlin, tells The Dispatch.

Kleinhans suggests that the much-publicized target of making 20 percent of the world’s chips by 2030 will be “impossible” to meet.

After dominating global chip production in the early 1990s—producing 45 percent of global output in 1990—the continent faced a stunning decline as producers offshored to East Asia, leaving Europe today with a measly 8 percent market share. Europe now ranks below every major player in the industry. Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea each individually produce more chips than the EU members combined. China produces 24 percent, and the U.S. about 10 percent.

“Even if all the newly announced fabs [semiconductor factories] come, Europe will still play a minuscule role in semiconductor manufacturing itself,” Kleinhans says. “This is simply in the nature of the semiconductor industry—front-end fabs are ridiculously expensive and rely on economies of scale.”

The proposed legislation emphasizes the bloc’s strengths in specialized technology, chip design and innovation. Dutch-based ASML, for example, is renowned as the world’s sole supplier of extreme ultraviolet lithography machines—essential to the production of the most advanced computer chips.

While Europe is therefore critical to the supply chain—and leads the U.S. in some areas—U.S. companies accounted for nearly 50 percent of the world market share for chip design in 2020 while the EU stood at 10 percent.

There is a question of scale that European policymakers hope to leverage with a U.S.-style subsidy package. But high-end chips, put bluntly, are not where the money is. China and Taiwan still dominate global manufacturing and packaging, using large-scale factories (known as fabs in the industry) to produce memory and analog chips en masse for use in cars, computers, and other widely shipped products. Julia Hess, a fellow at the German think tank Stiftung Neue Verantwortung, points out in a recent policy paper that the proposed subsidies do not cover production of these middle- and low-end chips, so-called “mature nodes”—even though it is here where China has the strategic edge. The European Commission is said to be amending the legislation to include lower-grade chips.

The Biden administration wants Europe to follow in its footsteps, using economic protectionism in its strategic pivot against the CCP. The Commerce Department’s Bureau for Industry and Security announced new restrictions on leading-edge chip companies exporting to China last October.

And the CHIPS Act is designed to attract companies from key allies—South Korea, Taiwan and Japan—to anchor in the U.S., drawing further capital away from China.

But European policymakers continue to debate how far they should align with the U.S., preferring to keep their intentions ambiguous by framing the subsidies within a wider move to “strategic autonomy.”

Thierry Breton, a member of the European Commission—the EU’s executive branch—emphasized that maintaining “openness” was essential to Europe’s response. “No country is self-sufficient when it comes to semiconductors due to the complexity, geographic specializations and deep interdependencies characterizing the supply chain,” he noted in a speech last year.

The comments preceded widespread European discontent about the effects of American protectionism on European firms—not just the CHIPS Act but also and especially the tax breaks offered by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Nevertheless, strategic cooperation is occurring, with U.S.-based Intel, a leader in advanced chip design, publishing a paper in September calling for greater transatlantic cooperation on semiconductors. The company has committed $33 billion to research and manufacturing in Europe.

Even aside from the geopolitical concerns, implementation is another problem.

Critics of the US CHIPS Act cite risks of rent-seeking by chip companies, as well as inefficiencies resulting from state support. It is unclear how European policymakers will yet address these concerns as the bill there continues through the negotiating process.

The commission’s proposal to use private sector data to directly monitor the chip supply chain and intervene through common purchasing when shortages arise is one controversy.

“The Commission seems to think governments can forecast the market better than the industry itself,” Kleinhans tells The Dispatch.

Nor is it clear how the proposed subsidies would be distributed within the bloc. The high capital costs associated with building fabs mean incentives are likely to go to companies that have already consolidated their position in the market.

Others point out that large-scale subsidy initiatives could collide with the EU’s own rules on the internal market, which guarantee free and fair trade between member states.

Once upon a time, wrote the Brookings Institute’s Constanze Stelzenmüller, Europe “outsourced its security to the U.S., its export-led growth to China, and its energy needs to Russia.” Tectonic shifts in geopolitics have shaken all three of those foundations, and the CHIPS Act is one attempt to give Europe what policymakers call “strategic autonomy.”

Reuters reports that EU lawmakers could pass the act within the next two weeks.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.