During one of the most pressing humanitarian crises facing the world today, the United States is doing little to rescue Uyghur refugees from what the American government has officially classified as genocide.

The United States admitted zero Uyghurs through its refugee admissions program in fiscal year 2021, a State Department spokesperson confirmed to The Dispatch on Thursday.

A recent State Department report on admissions details countries of origin for refugees who were resettled from the beginning of October 2020 through the end of September 2021. According to that document, not a single refugee of Chinese nationality—including Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities from Xinjiang—was resettled in America through the program in that time.

Asked why no Uyghur refugees were resettled, a White House spokesman referred The Dispatch to the State Department and said it is “something we take very seriously and something the president is committed to.”

Refugees from China have consistently represented a slim portion of total admissions in recent years, but a downward trend has been especially noticeable since 2016. There were none admitted through the program in fiscal year 2020, one in 2019, six in 2018, 24 in 2017, and 57 in 2016.

Part of this is because China makes it exceptionally difficult for refugees to escape. But those who do make it out of the country must also overcome bureaucratic hurdles and slow processing of their asylum claims.

“Everywhere is checkpoints, cameras. It’s very hard for people to move from one place to another,” Mustafa Aksu with the Uyghur Human Rights Project told The Dispatch of Xinjiang. He said Chinese officials refuse to renew or issue passports to Uyghurs and will confiscate passports from individuals who have them. And Uyghurs in other countries run into challenges when trying to apply for the refugee program because of administrative backlogs and issues like expired passports.

China has forcibly detained between 1 million and 3 million Uyghur Muslims and other ethnic minorities in detention camps in Xinjiang. Survivors of the camps have testified about being subject to horrific abuse while in detention. Tursunay Ziyawudun, a concentration camp survivor, told members of Congress earlier this year that she was raped by guards on multiple occasions and tortured with electric batons. She also described being malnourished, crowded with other detainees, and forced to renounce her religious beliefs.

“If we asked questions, we were beaten,” Ziyawudun testified.

Uyghurs in Xinjiang have also suffered forced abortions and sterilizations. Many have been victims of forced labor. Uyghurs who live in other countries aren’t safe from the Chinese government, either: CNN reported over the summer that several Muslim countries—under pressure by Chinese authorities—are extraditing Uyghurs to China.

Former detainees have said what is happening inside the camps amounts to crimes against humanity and genocide, and the United States government officially agrees: A day before the Trump administration handed over the reins to the Biden team, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared the Chinese Communist Party guilty of genocide against Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities. Current Secretary of State Antony Blinken assured lawmakers early on in the Biden administration that he agreed with the designation, and the State Department included it in its annual human rights report in March. The Biden administration’s report notes that the genocide is being perpetuated by officials with the approval of and at the direction of the Chinese government.

Despite the genocide designation, Uyghur refugees have dealt with delays and a lack of urgency in their asylum requests. The admissions program on the whole has also suffered from drastic decreases in the total number of refugees admitted to the United States.

During his one term, former president Donald Trump repeatedly set records for granting the fewest refugees entry since the modern resettlement program began in 1980. In fiscal year 2020, the United States let in just 11,841 refugees, which is far lower than the historic average of 90,000 annually. The massive drop in admissions that year was partly due to the coronavirus pandemic—but Trump slashed admissions to historic lows in his prior years in office as well. The United States admitted 30,000 refugees in 2019, 22,560 in 2018, and 53,716 in 2017.

President Joe Biden says he supports admitting more refugees, but his actions in office have not matched his rhetoric. He raised the refugee cap for fiscal year 2021 from Trump’s historically low 15,000 spots to 62,500 after facing pressure from Democratic lawmakers. But America allowed only 11,411 refugees into the country in total between October 2020 and the end of September—the lowest number since the refugee admissions program began in 1980.

Biden reportedly feared political blowback about raising the refugee cap from voters who might wrongly conflate it with the influx of asylees on the southern border.

Biden raised the refugee cap even higher to 125,000 spots for this fiscal year, and the State Department assured Congress in its report on the upcoming year’s refugee admissions goals that Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities facing persecution by China will be prioritized. Still, the administration has not yet formally extended a special priority status to Uyghurs to make it easier for them to apply for asylum.

The State Department has proposed an allocation of 15,000 spots for refugees from the East Asia region in fiscal year 2022, which includes those with China as their country of origin.

Because Trump slashed the refugee program each year, staffing and infrastructure is still in disarray and unable to respond adequately to the current demands of the refugee crisis. As admissions slowed to a crawl, resettlement agency offices across the United States were forced to shut their doors and lay off hundreds of workers.

The U.S. refugee program operates through public-private partnerships, and the private sector side of the equation—nine nonprofit resettlement agencies with local affiliate offices—looks to the administration to determine how much staffing and processing capacity is needed, Matthew Soerens with the refugee agency World Relief told The Dispatch. The government gives monetary support to the local offices for each refugee resettled to help with the person’s expenses during their first year in the United States. That often includes assistance with rent, food, language classes, and finding a job. Local churches, school districts, and law enforcement also collaborate with the agencies and assist with the transition. While volunteers are always a key part of the process, trained staff who are equipped to vet and interview refugees from all over the world are also essential.

According to a report by the liberal Center for American Progress, refugee agencies had to close or zero out the budgets of 134 affiliate offices. As the numbers of refugees admitted plummeted during the Trump years, World Relief was forced to lay off more than a third of its U.S.-based staff and close eight offices.

“We’re doing everything we can to ramp up, but we can’t just re-lease office space and rehire the exact same staff who were trained and had all the right relationships with churches and community partners,” Soerens said. “We’re not reopening them immediately. We can’t afford to do so.”

Refugee workers told The Dispatch that the Biden administration has not yet given their organizations much reason to beef up.

“It’s hard to tell if the continued low level of resettlement is COVID-related and how much is they weren’t prioritizing rebuilding the processing as quickly as possible,” Soerens said. He added that refugee agencies have communicated with the administration that if Biden is serious about meeting the new goal, “they really need to step up processing.”

Other experts are skeptical the administration can meet its new cap.

“I’ve still not seen a dedicated influx of resources to the refugee resettlement programs that would indicate they’re ever going to be able to process 125,000,” Elizabeth Neumann, former assistant secretary of counterterrorism and threat prevention at the Department of Homeland Security, told The Dispatch.

As the United States’s commitment to refugees and its ability to process cases remains in doubt, persecuted people are left waiting for relief, both abroad and in some instances, already in America.

There are Uyghurs in the United States who came legally—for work, school, or to visit—who then watched with horror as the situation in China deteriorated to the point where it was too dangerous for them to return. Many of these individuals decided to seek asylum in the United States, yet to the bewilderment of human rights advocates, the government has been slow to approve these requests. The delays result in even more challenges: While in limbo, some passports expire, making it more difficult for refugees to gain approval.

These families find themselves unable to move forward with their lives or shake the constant fear of deportation.

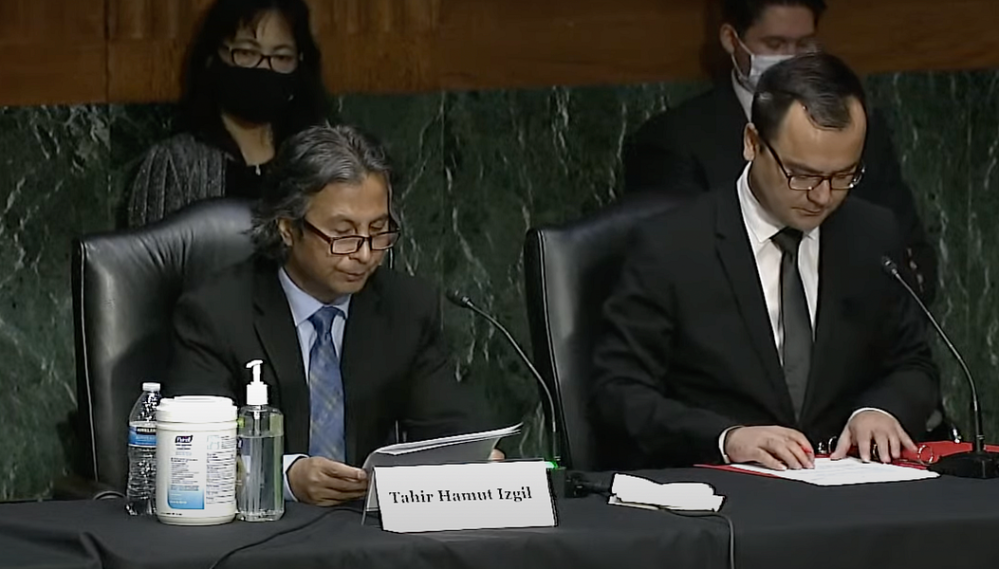

Tahir Hamut Izgil, a Uyghur poet and activist, is one of these people. He fled to the United States in 2017 with his family and sought asylum.

“I was one of very few lucky Uyghurs who was able to leave at that time,” Izgil told members of Congress this week. “Many other Uyghurs could not get the same opportunity. They couldn’t get passports, or their passports were confiscated.”

Izgil has waited for approval of his asylum claim for four years. He said his two daughters’ Chinese passports expired in 2019, and they now have no official status in America.

“Some Uyghurs in the United States have been waiting for asylum status for seven or eight years,” Izgil said. “Although some Uyghur Americans are living in safe conditions and have work opportunities in the United States, many have not been granted legal residency status and they are going through many hardships and anxieties. Many continue to receive threats from the Chinese government."

“At this time, when effective measures have not been taken to end Chinese genocide against the Uyghurs, it will give Uyghurs some hope for the future if the Congress passes a U.S. law to bring refugees to safety,” he added.

Some lawmakers are pushing for the United States to admit more Uyghurs and others being persecuted by the Chinese government—but the effort hasn’t made much progress since legislation with a bipartisan roster of supporters was introduced in both chambers in the spring.

“We must open our doors more widely to those seeking freedom,” Rep. Chris Smith, a New Jersey Republican, said this week.

Smith was one of several members of the Congressional Executive Commission on China who met Tuesday to hear from experts and refugees about how best to respond to the Chinese government’s genocide of ethnic Muslims in Xinjiang and its repression of Hong Kongers.

The lawmakers on the commission were largely in agreement: While the U.S. government has taken action to punish Chinese officials responsible for the genocide in Xinjiang and the crackdown on freedom in Hong Kong, including through sanctions, it is not doing enough to affirmatively help individuals hurt by these events. The United States, they argued, should admit more refugees from Xinjiang and Hong Kong—not only those being oppressed, but also high-skilled workers who want to come to America.

“In the face of egregious violations of internationally recognized human rights, we need to take concrete steps to protect those harmed by authoritarian governments,” said Sen. Jeff Merkley, the Oregon Democrat who chairs the commission. “While we cannot control the Chinese government’s behavior, we have the power to protect the persecuted who come to our shores.”

Experts on Tuesday told lawmakers the best way to help victims of the genocide is to grant them special humanitarian status to make it easier for them to apply for asylum. Rep. Ted Deutch, a Florida Democrat, introduced a measure to accomplish just that in March. Senators Marco Rubio and Chris Coons, respectively a Republican from Florida and Democrat from Delaware, quickly followed up with a companion measure in their chamber.

We previously covered the bill in Uphill:

The legislation extends “Priority 2” or P-2 status to individuals who are residents of or have fled Xinjiang who “suffered persecution or have a well-founded fear of persecution” on account of their peaceful expression of political opinions, religious or cultural beliefs, or participation in related activities. It also includes affected minorities who are residing in other parts of China and those who fled to other countries on account of those concerns but have not been firmly resettled yet. Spouses, children, and parents of such refugees are included as well, except if their parents are already citizens of a country other than China.

Offices involved in the legislative push said they had not heard from congressional leaders about when it might receive a vote. But action on the Hill is not ultimately needed: Biden is able to make the change unilaterally, as his administration did with Afghan refugees in August.

Unlike other types of refugee designations, Priority 2 status empowers refugees to apply for asylum directly to the U.S. government instead of going through other channels like the United Nations. It can also allow refugees to apply from outside their country of origin, which is key for persecuted groups within China. Many Uyghurs who have fled the Chinese government and are seeking asylum in the United States are currently living in second countries like Turkey.

Olivia Enos, a senior policy analyst for the Asian Studies Center at the conservative Heritage Foundation told The Dispatch that “for most victims of the Chinese Communist Party, applying inside of China is just not a possibility.”

Enos added that applicants are still subject to the stringent vetting that undergirds the refugee process before coming to the United States, but special humanitarian status makes it easier for them to begin the process.

She testified before Congress this week, urging the United States to take action soon. She described granting Priority 2 status as “a practical way to alleviate suffering.”

Enos also called for the United States to build a coalition of allies to resettle Uyghurs and to conduct diplomacy with countries under pressure to extradite refugees to China, including Turkey, Thailand, Kazakhstan, and Malaysia.

“The United States has an opportunity to tangibly assist Uyghurs and Hong Kongers, to demonstrate that we hear their cry for help,” Enos told lawmakers. “Will we answer it? Will we extend safe haven? That choice is ours."

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.