The fact that former President Donald Trump kept over 300 classified documents at his Mar-a-Lago resort home in Florida—as well as his aides’ public insistence that he had a “standing order” to declassify any documents he took with him to his residence—have rekindled interest in America’s opaque classification system and the president’s role within it.

Evan Corcoran, one of Trump’s attorneys, even went so far as to claim that the president’s “constitutionally-based authority regarding the classification and declassification of documents is unfettered” in a May 25 letter to Department of Justice Counterintelligence and Export Control Section (CES) Chief Jay Bratt. (Corcoran’s letter was released Friday afternoon as an attachment to the partially redacted affidavit the FBI submitted while applying for a search warrant for Trump’s home.)

Although none of the three statutes listed in the FBI’s search warrant relate directly to classified information, the fact that the government alleges classified documents were improperly stored and handled is likely to be central to DOJ’s investigation.

“As a practical matter, I think it’s highly unlikely [Trump] would be charged for willful retention of [National Defense Information] unless the documents were classified,” David Laufman, a former CES chief, told The Dispatch. “The fact that the documents are classified makes stronger the case that they contain information relating to the national defense.”

Government secrets have been around forever, but our classification system is a relatively recent invention, as Klon Kitchen detailed in Thursday’s Current.

The 1917 Espionage Act—one of the statutes referenced in the FBI’s search warrant—predates the classification system. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8381, a March 1940 directive pertaining to “vital military and naval installations or equipment,” cited the Espionage Act as the basis of presidential classification authority. Eleven years later, President Harry Truman’s EO 10290 “dropped any reference to any particular statute, referencing instead ‘the authority vested in me by the Constitution and statutes, and as President of the United States,’” Yale law professor Oona A. Hathaway noted in a recent Minnesota Law Review article.

Since Truman, the classification system has been regulated almost exclusively via executive order, most recently EO 13526, signed by Barack Obama in 2009. Classification covers information—including sources and methods—that, if disclosed, could harm national security. Information may be classified as “Top Secret” if its unauthorized disclosure “reasonably could be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security,” Obama’s executive order says. “Secret” information is applied to information that could cause “serious damage,” and “Confidential” information for “damage.”

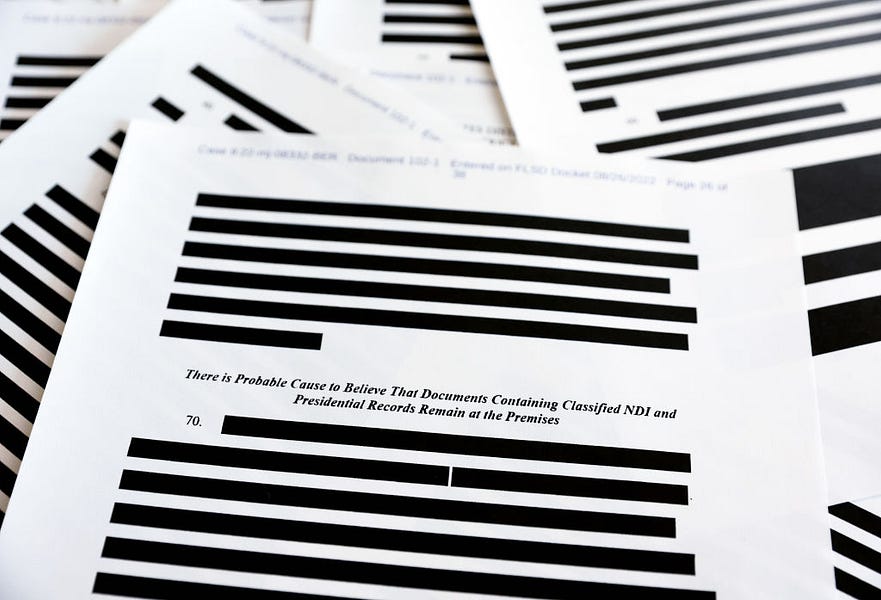

In May, when the FBI reviewed the 15 boxes of documents Trump had sent from Mar-a-Lago to the National Archives in January, it found “67 documents marked as CONFIDENTIAL, 92 documents marked as SECRET, and 25 documents marked as TOP SECRET,” according to the affidavit released Friday. All but one of the 15 boxes contained classified documents. When the National Archives referred the case to the DOJ in February, it noted that “highly classified records were unfoldered, intermixed with other records, and otherwise unproperly identified.”

In addition to the three levels of classification, documents can be further restricted as “sensitive compartmented information” (SCI).

“The background investigation for SCI access is the same as for Top Secret access, so they are often written together as ‘TS/SCI,’” Hathaway wrote. But to access SCI, “a person must be granted specific access to the compartment” and be “read into” the program,” Hathaway wrote. “Programs, in turn, are generally known by their designated codeword, which is itself classified.”

By virtue of their office, members of Congress do not need security clearances to see classified information, though their staffs do. But members of Congress must have a “need-to-know” in order to access SCI.

In the affidavit, the FBI special agent stated that some of the documents Trump retained were marked as “HCS,” an “SCI control system designed to protect intelligence information derived from clandestine human sources.”

While the basic architecture of the system has stayed roughly the same since Truman, the volume of classified information has greatly increased. Only a relatively small number of high-level officials have “original classification authority,” meaning they get to decide to classify information so long as they can “identify and describe” the national security risks of its unauthorized disclosure. But over 4 million of their employees with security clearances can produce documents with “derivative classification.” According to Hathaway, “derivative classification happens when a new document is created that uses information that has already been classified.” In 2017 alone, over 49 million documents were classified derivatively.

So what exactly is the president’s authority? One commonly cited view comes from Justice Harry Blackmun’s majority opinion in the 1983 Supreme Court case Department of the Navy v. Egan.

“The President, after all, is the ‘Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States,’” Blackmun wrote, referencing Section 2 of Article II of the Constitution. “His authority to classify and control access to information bearing on national security … flows primarily from this constitutional investment of power in the President and exists quite apart from any explicit congressional grant.”

Corcoran, the Trump attorney who wrote the DOJ in May, tied his claim that the president’s classification and declassification authority is “unfettered” directly to this quote from Blackmun.

Although the courts have tended to defer to the executive branch in matters of national security, the presidential classification authority is not dictatorial. In a 2009 paper, separation of powers specialist Louis Fisher notes that Blackmun’s “language only affirms that the President may act in the absence of statutory authority, not against statutory authority.” In theory, Congress could pass legislation tinkering with the system. But aside from passing the 1946 Atomic Energy Act—which automatically restricts all information related to atomic weapons technology—it has not.

Hathaway—who worked as a lawyer at the Department of Defense during the Obama administration—wrote that “the incentives for everyone in the process almost always run in the direction of classifying up, rather than down. … The personal and professional penalties for getting it wrong by overclassifying are dwarfed by the professional penalties for getting it wrong by underclassifying.”

Per Obama’s executive order, the vast majority of documents come up for review after 25 years—and, if they are not declassified then, another 25 years after that. The executive order does not explicitly list the president as one of the people with declassification authority, but he is widely understood to hold it and can exercise it unilaterally. George W. Bush declassified a 2001 presidential daily briefing regarding Osama bin Laden in 2004, for example.

Because the sources and methods of multiple intelligence agencies may be at risk when information is declassified, “the custom and practice is for the administration to confer with the intelligence community if it intends to seek declassification of something to give them a chance to be heard,” Laufman said.

With that custom and practice in mind, Trump’s allies’ claims about a “standing order” to declassify any documents taken into the residence don’t stand up to scrutiny. Several former members of the Trump administration and national security and intelligence officials told CNN last week the claim of a standing order was false and nonsensical.

“A decision as significant as declassification of sensitive national security information would be contemporaneously memorialized at the time,” Laufman said. “There’s no indication, notwithstanding statements by Mr. Trump’s representatives to the contrary, that there was any kind of memorialization of any real decision while he was still president to declassify something.”

Furthermore, when information is declassified, it is done “methodically, piece by piece,” Laufman said. “It’s not some giant glob of encoded declassification utterance or some ephemeral thought bubble of ideation that results in an actual declassification. What we are seeing I think fairly can be construed as kind of a post hoc effort at retroactively declassifying information in his status as a former president, rather than while he still served as president of the United States with constitutional powers as commander in chief.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.